Tim’s Vermeer—Vermeer’s Music Lesson—Marker’s La Jetée

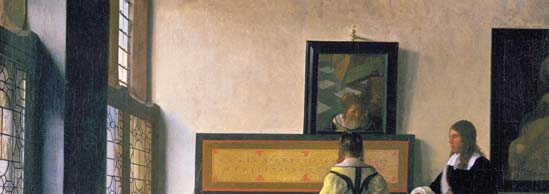

This being the film issue and all, I thought I’d try my hand at a piece about arguably the greatest filmmaker of all time—great-grandfather, at any rate, to all the rest of them—that being, of course, Johannes Vermeer of Delft.

The animating occasion for this meditation: the recent release of Tim’s Vermeer, the magician-skeptics Penn and Teller’s documentary film about their Texas-based inventor friend Tim Jenison and his remarkable experimental investigations into precisely how the seventeenth-century Dutch master might have been able to render all those astonishing paintings. And I should say at the outset that Jenison, for his part, comes off as a wonderfully ingenious and thoroughly congenial fellow. And who knows? He may even be right.

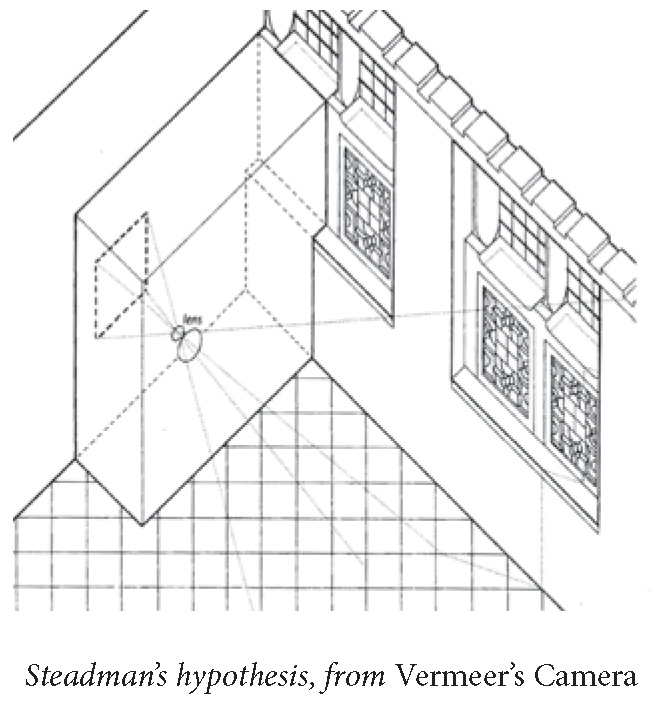

He’s hardly the first to have become convinced that Vermeer must have been using some sort of optical devices. David Hockney (who also shows up in the film) devoted many pages to the likelihood in his 2001 book, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, and Hockney in turn frequently cited the meticulous investigations of Philip Steadman, who in his 2001 book, Vermeer’s Camera: Uncovering the Truth Behind the Masterpieces (and in subsequent BBC documentaries, also referenced in the Penn and Teller film), laid out the basis for his own conviction that Vermeer must have been using a camera obscura, which is to say an entire dark room, or at any rate a narrow closet, slotted off the side of his studio with a pinhole lens facing the scene before it.

But Jenison does move this line of speculation considerably for-ward in several beguiling ways, notably by suggesting that Vermeer might have used a circular, flat mirror, maybe an inch or two in diameter and held out at a forty-five-degree angle from the tip of a stick mounted atop the horizontal canvas, so as to help him get the color details of the scene before him so precisely right (by gazing at the edge of the image reflected in the mirrored circle and then beyond that onto the patch of canvas being painted down below and mixing the pigments down there until the two images matched). Even more intriguingly, Jenison winds up arguing (based on months and months of trial-and-error efforts of his own) that Vermeer may not have had to use an entire dark room after all: rather, drawing on some of Hockney’s most suggestive intuitions, he demonstrates how a con-cave curved mirror affixed to the far wall, and focusing the image of the scene before it onto that flattened circular one, could have worked just as well, in fact substantially better, and...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in