Remember how last time we were talking about Robert Irwin and his brilliantly confounding installation at the Whitney—the restaging, this past summer, of that 1977 piece of his in which museum visitors were delivered from out of the elevator onto an amorphous fourth floor entirely pithed of its usual internal walls and struts and light fixtures and transfigured into a seemingly empty football-field-sized space (all ceiling hive and slate-grid floor),  though one bisected by a vast, translucent swath of taut scrim, stretching all the way across the length of the vastness from the far left to the far right, from ceiling down to eye level, whose fabric seemed to catch and hold the natural light of day as it poured forth, tide-like, from that strange, trapezoidal window way over to the left: a space, in short, initially almost impossible to put together in one’s mind, the occasion for a sort of perceptual free fall in which one actually got to experience, momentarily, as if in drop-jawed slow motion, all the sorts of things one is constantly doing to get one’s perceptual bearings in the world? Getting to “perceive oneself perceiving,” as Irwin likes to frame things, being for him the ultimate function of art.

though one bisected by a vast, translucent swath of taut scrim, stretching all the way across the length of the vastness from the far left to the far right, from ceiling down to eye level, whose fabric seemed to catch and hold the natural light of day as it poured forth, tide-like, from that strange, trapezoidal window way over to the left: a space, in short, initially almost impossible to put together in one’s mind, the occasion for a sort of perceptual free fall in which one actually got to experience, momentarily, as if in drop-jawed slow motion, all the sorts of things one is constantly doing to get one’s perceptual bearings in the world? Getting to “perceive oneself perceiving,” as Irwin likes to frame things, being for him the ultimate function of art.

A few weeks later I happened to be in Los Angeles and took advantage of the occasion to visit the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s concurrent retrospective survey of the work of Irwin’s onetime confederate James Turrell (the two had worked quite closely together at a fulcrum moment in each of their respective careers, during the late ’60s and early ’70s, though they’d gone their separate ways thereafter), and once again, like every other visitor to the show, in room after room, time after time, I was thrust into these moments of jaw-dropping experiential vertigo. (Turrell’s work can be so perceptually upending that in one famous instance, several decades ago, at his Whitney retrospective, one woman literally lost her footing and collapsed to the floor, spraining an ankle and thereafter suing both the artist and the museum for infliction of bodily harm: a singularly bracing review if ever there was one.)

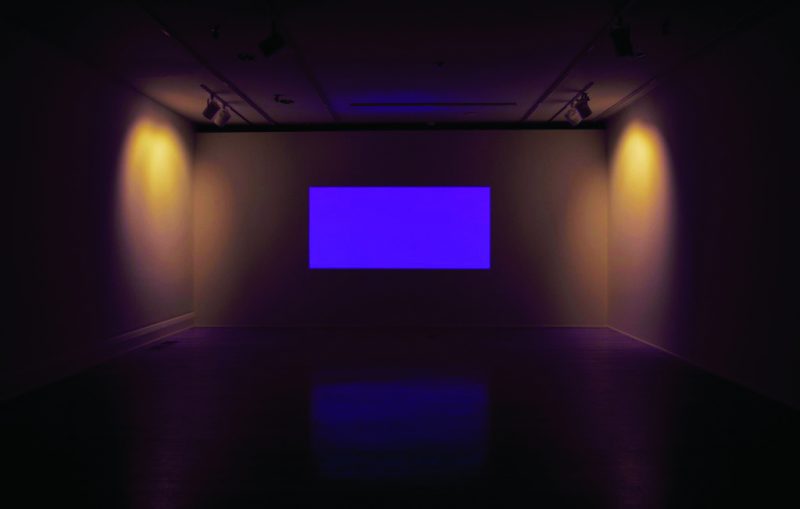

In one room in particular at the LACMA show, one found oneself coming around a bend and there, on the far wall—or, wait, was it on the wall, or in the wall?—anyway, there was this fathomlessly deep, purpley-blue rectangle, utterly uniform in its appearance. How had he ever painted the thing? How could he have achieved such an even application of paint, and such luminous paint at that? Although, wait a second—was it paint? Maybe it was some sort of light box hanging out from the wall. Was “it” even there? Hesitantly, gingerly, one approached the purple rectangle—and was the thing actually almost throbbing, or was that just a trick of the eyes? For that matter, how had he managed those incredibly crisp, knife-sharp edges? Until, just a few inches from the wall, the whole piece fell away, almost literally, and one was confronted by a hole in the wall: a clean rectangle cut into a purple cave, or, rather, a white-walled aquarium of diffuse, powdery, violet-tinted light, light emanating from god only knows where. Magic!

And once again, one was given access to this sense of one’s sensory faculties as constantly active agents in the ongoing constitution of the world: the prehensility of one’s sensorium, as it were, the way sight might be understood as having a notional opposable thumb, such that it is constantly reaching out and grappling with the world it is receiving, turning it to this side and that, getting its bearings. Phenomenologists like to talk about intentionality, how all thought is thought of something, toward something—all experience is experience of something: it is directed out toward the world, but, until seeing the Irwin and Turrell shows in such close succession, I hadn’t so much realized the way that being in the world is in itself a species of constantly falling forward (tending forward, in that sense), of reaching out and steadying oneself and probing for solid footing in a constantly transmogrifying world. Most of the time we do all this automatically, as if by rote, so that we seldom stop (or are brought up short often enough) to think about it.

And once again, one was given access to this sense of one’s sensory faculties as constantly active agents in the ongoing constitution of the world: the prehensility of one’s sensorium, as it were, the way sight might be understood as having a notional opposable thumb, such that it is constantly reaching out and grappling with the world it is receiving, turning it to this side and that, getting its bearings. Phenomenologists like to talk about intentionality, how all thought is thought of something, toward something—all experience is experience of something: it is directed out toward the world, but, until seeing the Irwin and Turrell shows in such close succession, I hadn’t so much realized the way that being in the world is in itself a species of constantly falling forward (tending forward, in that sense), of reaching out and steadying oneself and probing for solid footing in a constantly transmogrifying world. Most of the time we do all this automatically, as if by rote, so that we seldom stop (or are brought up short often enough) to think about it.

Once I stepped back from gawping into Turrell’s piece (St. Elmo’s Light, 1992, according to the wall leg-end), I noticed that another person had drifted into the room behind me, someone I swore I knew. But who? A friend from somewhere (which is to say I felt pleasantly disposed toward him, and he in turn seemed to knowingly return my look of vague recognition)? And now we proceeded to go through that dance, both of us trying to decide whether to go over and greet the other or not, both of us, it seemed, momentarily clueless as to the other’s actual identity, rifling through our memory banks for some clue. Or, alternatively, we could each still make like we hadn’t even noticed the other. He was youngish, nebby—well-worn blue jeans, scuffed tennis shoes, clean-shaven, a dark cotton hoodie draped over his head, hands stuffed into the hoodie’s shallow pockets as he in turn now seemed to shift his gaze back to the mystery of the purple rectangle. I stepped back, still flummoxed: I could swear… At which point a pair of young ladies stepped into the room, one of them whispering something excitedly to the other, of which I was able to make out only the single word Newsroom. For of course, that was it: the guy must be one of the cast members of the HBO series (and his look of recognition rather the wary acknowledgment that I, like everyone else, had noticed this fact, probably mingled with the vague hope that I wasn’t in fact going to come over and harass him). But which cast member? For I now found myself falling into a whole new vertiginous abyss. This wasn’t like the moment in Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer where the protagonist, Binx Bolling, out on his daily walkabout through the streets of New Orleans, happens upon none other than the legendary Hollywood heartthrob William Holden, in town shooting a picture and shedding his heightened “resplendent” reality all about himself, like a star, such that this particular street corner would now become forevermore the corner where he’d spotted William Holden. If any- thing, my guy was standing there like an anti-star, the cipher of somebody I should know but didn’t quite.  For one thing, no wonder I hadn’t recognized him: his character was supposed to be in New York, not Los Angeles (even though the show, conspicuously set in New York, was probably shot in LA). But then, too, as I continued to cast about, he struck me as half of a dyad on the show, one of two characters both in love with the same woman—one, the more friendly and approach-able of the two, a floundering sort of fellow, and the other, more competent and less approachable, a straight-ahead professional sort.

For one thing, no wonder I hadn’t recognized him: his character was supposed to be in New York, not Los Angeles (even though the show, conspicuously set in New York, was probably shot in LA). But then, too, as I continued to cast about, he struck me as half of a dyad on the show, one of two characters both in love with the same woman—one, the more friendly and approach-able of the two, a floundering sort of fellow, and the other, more competent and less approachable, a straight-ahead professional sort.

And, that was it; that was the thing: the guy in the room beside me was the more professional of the two, but here he was, disguised to all the world as a schlemiel. No wonder I’d had such a terrible time placing him. The point, I suddenly realized, is that that’s how social reality goes as well, much the same as with perceptual reality: we are continually falling onward and forward into the next interaction, staggering and grasping for this stray handhold there or that next solid clue there—social life, just below the surface of our awareness, being a continual vortex of indeterminacy constantly resolving itself toward apprehension.

And, that was it; that was the thing: the guy in the room beside me was the more professional of the two, but here he was, disguised to all the world as a schlemiel. No wonder I’d had such a terrible time placing him. The point, I suddenly realized, is that that’s how social reality goes as well, much the same as with perceptual reality: we are continually falling onward and forward into the next interaction, staggering and grasping for this stray handhold there or that next solid clue there—social life, just below the surface of our awareness, being a continual vortex of indeterminacy constantly resolving itself toward apprehension.

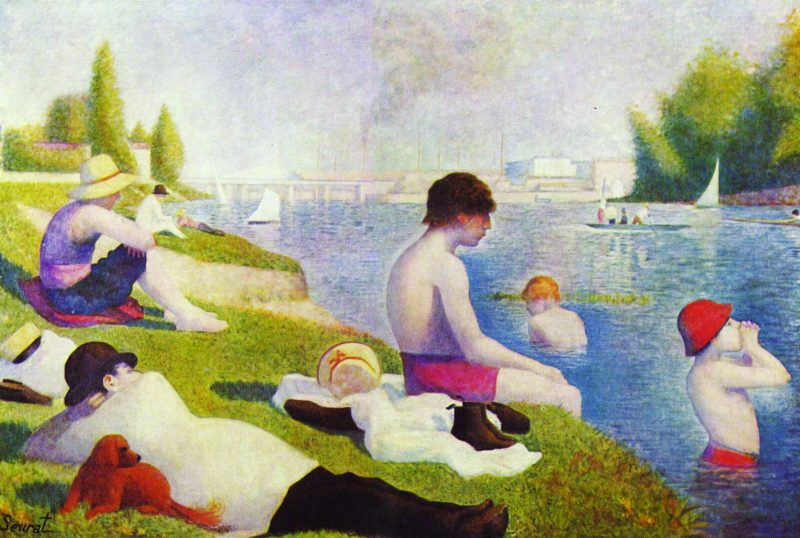

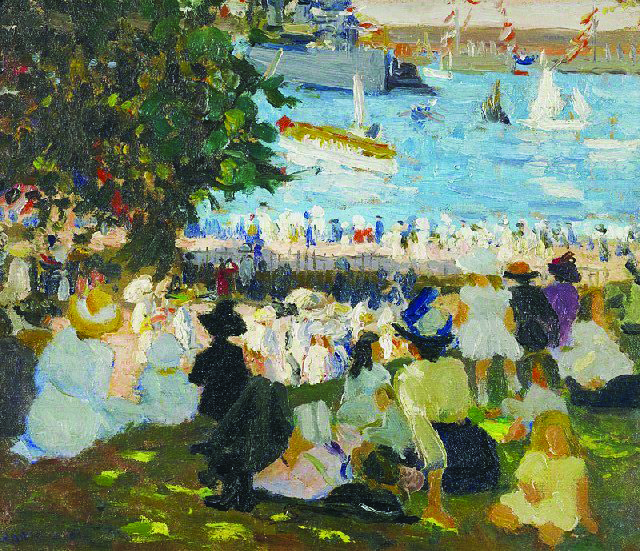

And then, a few days later, I got an email from my pal Michael Benson. He’d just come upon a color photo in that morning’s digital New York Times of a group of onlookers atop a hill, seen from behind and looking down on the resurfacing operations around the capsized Costa Concordia cruise liner, and he was sure it was based on some impressionist painting, but it was driving him crazy;  he’d spent the last few hours cruising the internet and he was damned if he could locate it (all sorts of close calls, but no exact match or corollaries). He knew I loved this sort of thing, so he was only too happy to hand the riddle off to me, and so now, of course, I too fell into the wikivortex, trying to nail down the reference, scrolling past such near-misses as Seurat (perpendicularly, twice) and, of course, Manet (seen from the other side) and other suchlike, sending the query off to other similarly obsessible friends who returned with other possible candidates (even one from an Australian copycat impressionist named Ethel Carrick Fox)…

he’d spent the last few hours cruising the internet and he was damned if he could locate it (all sorts of close calls, but no exact match or corollaries). He knew I loved this sort of thing, so he was only too happy to hand the riddle off to me, and so now, of course, I too fell into the wikivortex, trying to nail down the reference, scrolling past such near-misses as Seurat (perpendicularly, twice) and, of course, Manet (seen from the other side) and other suchlike, sending the query off to other similarly obsessible friends who returned with other possible candidates (even one from an Australian copycat impressionist named Ethel Carrick Fox)…

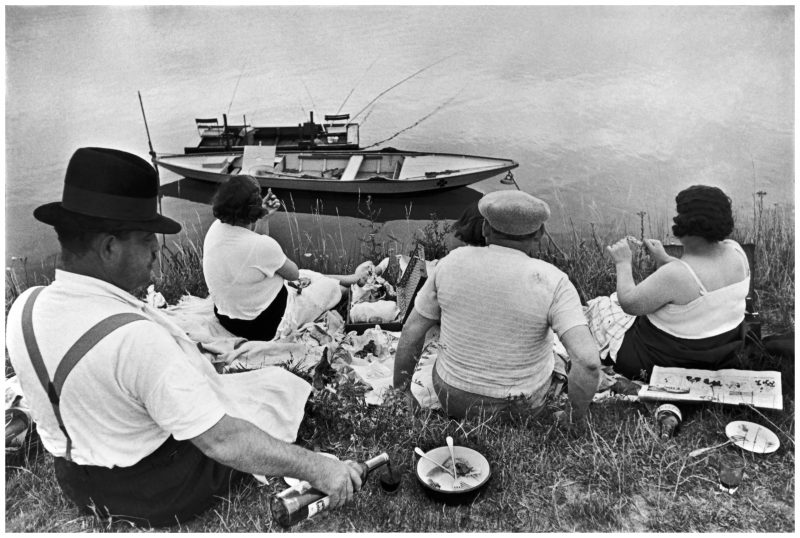

…and I was getting all set to offer up a brand-new theory of cultural transmission, about the way certain images summon up so many near-miss corollaries that we synthesize the fantasy of a composite original, imagining we’ve actually seen that notional combine somewhere before, hence the whiff of déjà vu, when, at the last minute, and before I could make a complete fool of myself broadcasting my new theory, another friend of mine clocked in with the solution to the whole damn puzzle: for the Times color photo was obviously a salute (possibly unconscious, though more likely quite intentional) to the classic 1938 black-and-white photo Sunday on the Banks of the Marne by Henri Cartier-Bresson, right down to the little docked skiff there by the riverside.

Doubtless one thing we’d been thrown by was the fact that the Times image was in color, and hence we’d all gone off scrambling for a color referent, which was to say a painting. But no doubt one of the reasons Cartier-Bresson must have been drawn to this particular “decisive moment” of com-position (either in the initial taking of the picture or else subsequently in the focusing upon that specific image amid all its siblings there in the darkroom) was because of the way his own cultural sensorium had itself been primed to receive it through earlier exposure to the Seurats, the Manet, and so forth.

Sunday on the banks of the River Marne.

Which is how it goes in the cultural, much as in the perceptual and the social realms. We are continually falling forward, grabbing what-ever handholds we can (even if those handholds are past instances, such that we keep falling forward into the past), haplessly reaching out for what-ever purchase might help afford us momentary traction in the maelstrom of converging sense impressions that is the ongoing, endlessly immediate experience of everyday life.