I. DYNAMITE

In 1868, the West was a mythical place, a land associated with boundless acreage for the speculator, infinite glory for the intrepid mountaineer, and rich veins of ore for the prospector. Just a few years before the American centennial, very little was actually known about what lay beyond the 98th meridian. This invisible line––which runs through the heart of Texas and cuts the corners off Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska––was at that time on the far side of America’s western border. Maps depicted the area with a few chicken-scratches for hypothetical mountain ranges and designated it with the words The Great American Desert.

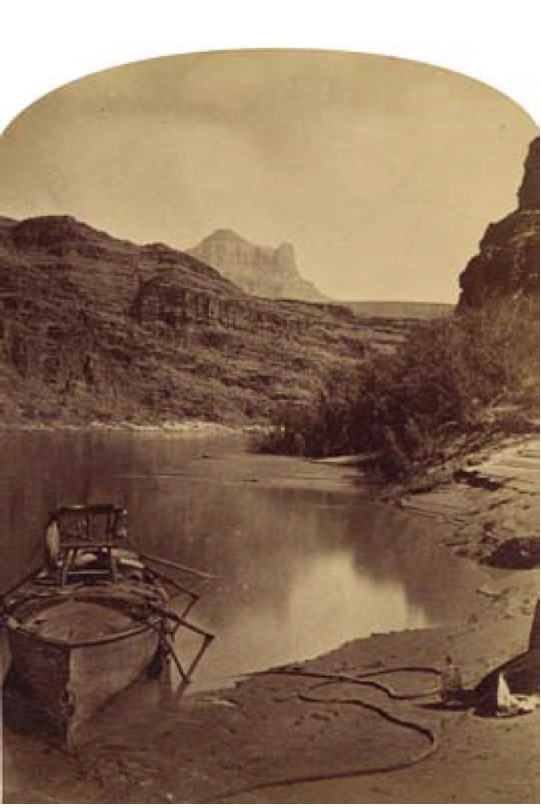

As European explorers ventured into India and Africa, an American self-styled naturalist named John Wesley Powell took it upon himself to map the unexplored territory of the West and catalog its resources. Powell was an unlikely mountain man. Although physically fit, with a barrel chest and the full beard that was his trademark, he’d lost an arm as an officer in the Civil War, and much of his scientific training consisted of reading voraciously from books sold by traveling salesmen. With his characteristic energy, Powell mustered a small group of hunters and former Civil War soldiers, including his brother, to mount a cartographic expedition down the length of the Colorado River. The success of this expedition made Powell, for a brief time, a national hero, and gained him the financial support he needed for his most ambitious undertaking—to map the entire West, including every stream, river, and pool of runoff.

At this time, the American government was in thrall to the expansionist goals expressed in the idea of Manifest Destiny: Americans had the divine right—the responsibility—to expand across the continent. The futurist writer and governor of Colorado, William Gilpin, did his part to aid Manifest Destiny. A speculator who believed his landgrabs to be divinely sanctioned, he vividly described the West to Eastern newspapermen and eager audiences as a second Eden, a fertile land with bountiful aquifers deep below the desert surface. Gilpin played fast and loose with scientific facts, inventing rainfall, diverting streams, and telling anxious farmers not to worry about rumors of aridity, because “the rain followed the plow.”

Powell, however, recognized early on that the West would be inhospitable to traditional large-scale farming, and foresaw that irregular rainfall would create a reliance on irrigation. This meant that the West would come to be defined by water rights. Without government regulation, he warned Gilpin and others in Washington, wealthy speculators would gain complete control over water, creating a feudal system that left farmers in the dust.

Powell published his preliminary findings in a federal report, still believing that there was time...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in