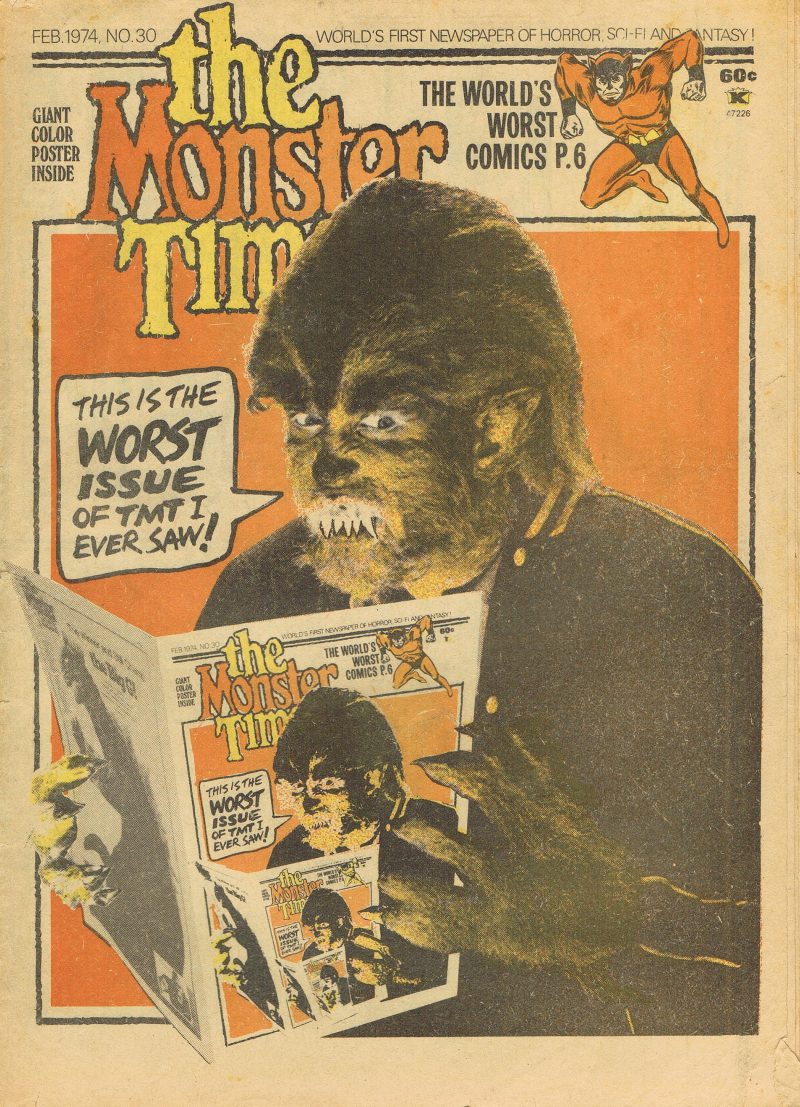

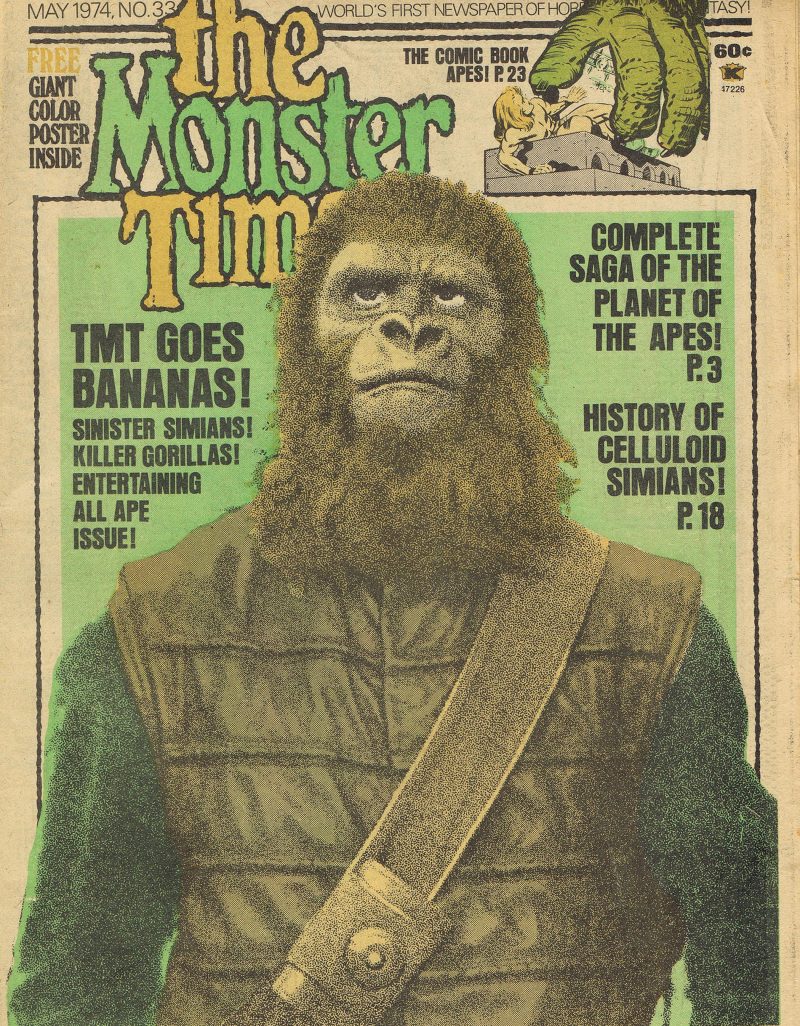

Here’s me at nine, circa the first stirrings of Watergate and the first visible rat incisors growing from the jaws of the Nixon administration: four-eyed, skinny as a chicken bone, in love with my shamrock-green Ross with black banana seat, sixty-five pounds if I weighed anything at all. It was 1972, and more than anything else I’d been seduced by something that reached into a deep black-and-white past and held what seemed to be unfathomably arcane secrets: horror and science-fiction movies. Sometimes new and in theaters but most often on broadcast TV, as the local channels filled their docket with cheaply licensable old genre entries from the studio vaults, the films I absorbed came to me like lost signals in space, aimlessly emanating from a history no one spoke about. Abbott and Costello comedies and Oscar-winning mammoths like Ben-Hur were common, but how could a kid, any kid, be tempted by these tame familiarities over some freakish text called The Hideous Sun Demon?

It seems funny now, but the absurd and even hokey films I couldn’t resist also regularly gave me nightmares. Our house sat on the corner of a lightless, ill-paved old country road surrounded by woods and the occasional farmhouse, and when I awoke at night it was down that road that I imagined various Frankensteins or werewolves lurking and approaching through the blackness of Long Island. The dance that Haley Joel Osment did during his nerve-wracked midnight trip to the toilet in The Sixth Sense? That was my dance, too. Too often I’d knock on my parents’ locked door, waking them from a chronically drunken stupor, to ask for a drink of water I was perfectly capable of getting on my own. Wiped out, my mother would stand by the sink, the cats looping softly around our ankles, and she would tolerate me for a minute or two, the middle son who was already proving to be the most troublesome of her three troublesome children.

But no nightmare could curb my appetite for the stuff, which I’d prime every weekend, when we’d get the Sunday Newsday, five times as thick as it is today, and the staple-bound weekly TV-program guide included therein. This was itself a thick blast of business, with wry and passionate synopses written anonymously by a staffer, later revealed to be John Cashman, who received more fan mail than the paper’s regular film reviewers did. (His summary of 1957’s From Hell It Came was one line long: “And back it should go.”...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in