June 12, 1972. The day America opened wide and said ahh. A movie starring a couple of no-name actors, directed by a middle-aged beauty-salon owner from Queens who’d cut more hair than film, with a script written over a single weekend, played for the first time at the World Theater in Times Square. The nation’s mouth gaped in a mixture of excitement, horror, fascination, and disbelief. Deep Throat was the X film that went mainstream. It became a genuine sensation, one of the most profitable films ever made, costing a mere twenty-five thousand and bringing in a whopping six hundred million. It was responsible, as well, for ushering in the era known as “porno chic,” middle-class respectable-types getting hardcore about hardcore. The New York Times Magazine devoted five pages of eggheady rumination to it. Johnny Carson and Bob Hope cracked wise about it. And Truman Capote’s high-society swans migrated down to low-life venues to see it.

If the mouth gapes watching Deep Throat these days, however, it’s likely as not because a yawn’s coming on. Deep Throat is no Ulysses or Lady Chatterley’s Lover. It’s not even a Candy or an I Am Curious (Yellow). It is, as location manager Len Camp so succinctly put it, “a piece of shit” with actors who “are all shit.” Even Gerard Damiano, the director, when asked if he judged it a good movie, said (after a long pause, as if such an admission pained him), “No.”

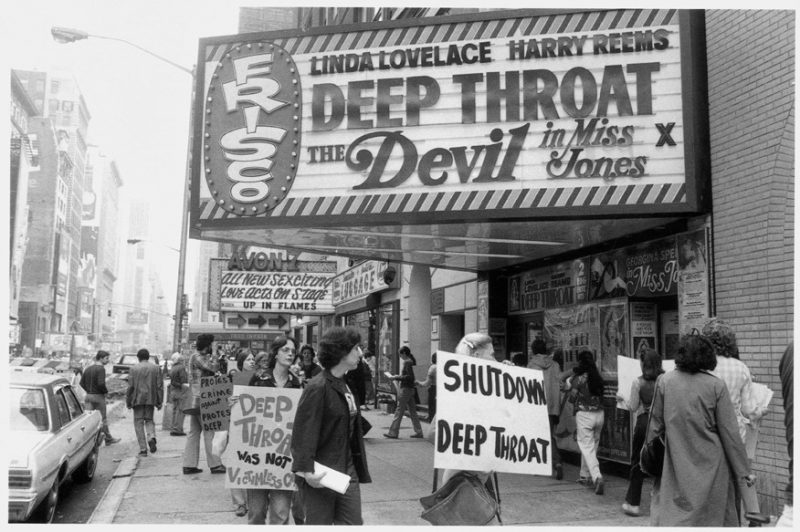

Even by the diminished standards of the early-’70s hardcore world, Deep Throat was considered a modest venture. Linda Lovelace, a relative newcomer to the Adult scene, played the lead, a character named Linda Lovelace. Harry Reems, who had originally been hired as the lighting director, was cast opposite her as Dr. Young. And in the supporting role of Helen, Linda’s older, wiser friend, was Dolly Sharp. Ted Street played the Delivery Boy. It’s tough now to understand what all the fuss was about, the furor and the controversy and the endless legal battles. (Reems was prosecuted in Tennessee for breaking obscenity laws, and found guilty. He would’ve gone to jail for up to five years but for the grace of an Alan Dershowitz–orchestrated appeal and legal-defense fund-raisers thrown by the likes of Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson.) From a present-day perspective, Deep Throat looks like a junky little nothing of a porno flick, your garden-variety suck-and-fuck loop—well, suck-and-suck-some-more loop, if you want to get technical—too dopey and good-natured to...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in