On YouTube, you can find hundreds of clips from the animated G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero. It’s been twenty years since the show premiered, but the gaudy palette and campy characters shimmer on the smallest screen. Collectively, these digital relics from an era when the real U.S. military was busy invading Grenada and Panama have been viewed hundreds of thousands of times.

It’s fascinating to view the series’s frenetic opening sequence, in which righteous American commandos battle the evil Cobra army. We meet G.I Joe, as he storms a beach outpost; Flint, wearing his cocked beret; Lady Jaye, throwing spears and clad in sexy olive fatigues; and Shipwreck, dashing into combat dressed like one of the Village People.

Then the Cobra villains emerge, blasting away with laser guns: the mutated snake-man, Serpentor; the leather-clad dominatrix, Baroness; and the mustachioed quack, Dr. Mindbender. Airplanes, boats, tanks, hang gliders, hovercrafts, jeeps, and a supersweet aircraft carrier zoom through the fray. Every image is paired with a shiny Hasbro toy in the Christmas catalog.

G.I. Joe was one of the pioneering “program-length commercials.” By creating an entire television series around a product, these shows dodged FCC regulations that limited children’s advertising. Animated characters helped sell everything from gummi bear candies to He-Man dolls, but G.I. Joe drew more criticism for encouraging both consumerism and militarism.

In 1982, Hasbro’s initial $4 million advertising push for G.I. Joe was the most money the company had ever spent on a single line, spawning a virtual military-toy-industrial complex. Around that time, critic William Crawford Woods wrote a blistering Harper’s essay about G.I. Joe, in which he investigated how the toy company “aimed to reach 95 percent of all American boys aged five to eight more than fifty times each.”

Perhaps Dr. Mindbender embodied Hasbro’s remorse for messing with kids’ brains. He wore a bushy robber-baron mustache, a monocle, a cape to accent his naked muscles, and, most strikingly, an armored crotch-plate. In one issue of the G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero comic book, Dr. Mindbender sells multimillion-dollar Cobra fortresses to Latin American revolutionaries. These “Terrordromes” emit sinister Paranoia Rays—mind-control beams that drive peaceful populations to revolution.

This fictional fortress had a real-life toy counterpart. (You can find the original commercial for the Cobra Terrordrome on YouTube as well, of course.) The play-set, which retailed for forty-five dollars (ninety in today’s money), is a shiny example of mid-1980s plastic-work run amok, comprising a circular fortress studded with gun turrets, a prison cell, a jet fighter, and fake computers.

As the toy line became popular, Woods worried that this childhood consumption would indoctrinate prospective soldiers: “The new G.I. Joes, as highly contemporary figures, commend war not as remembered ritual but as a future choice.… the notion that playing war is a rehearsal for waging war tomorrow has led to the banning of war toys in Sweden and by some American toy chains,” he wrote.

As an eerie reminder of his prophecy, a national newspaper search for G.I. Joe references turned up thirty-five obituaries for soldiers killed in Iraq since the war began, in 2003. In each article, family members reminisced how the men had loved to play with the toy soldiers.

It’s been twenty-five years since children first played at “waging war tomorrow” with G.I. Joes, and by coincidence or not, some of Hasbro’s old customers are now fighting a real war. The rehearsal is over. What did Dr. Mindbender teach us?

*

“Toy soldiers are among the oldest known toys, excavated from ruins throughout the ancient world, in Syria, Egypt and Asia,” writes psychologist Jeffrey H. Goldstein in his study of violence and popular culture. He explained that tin soldiers were first mass-produced by German toy makers in 1760—by stamping military figures out of flat sheets of tin.

By the nineteenth century, these two-dimensional toys had become an integral part of German boyhood. “Many parents also appear to have believed that toy soldiers were excellent tutors on current events. Every major international crisis or conflict brought forth an answering wave of tin soldiers,” wrote political scientist David D. Hamlin in his book Work and Play: The Production and Consumption of Toys in Germany, 1870–1914.

By 1890, American companies began to manufacture toy soldiers. G.I. Joe didn’t arrive on the scene until 1964. Hasbro released foot-tall G.I. Joe dolls for boys that year, hoping to cash in on the success of the Barbie doll. Historian Gary Cross describes this evolution of war play in his book Kids’ Stuff: Toys and the Changing World of American Childhood: “Like Barbie, G.I. Joe was accessorized. Hasbro adopted what was often called the ‘razor and razor blade’ principle of marketing. Once the boy had the doll he needed accessories—multiple sets of uniforms, jeeps, tents, and weaponry.”

From the very beginning, the Mindbender merchandising model was already in place. Someday, G.I. Joe’s tents and jeeps would evolve into massive Terrordrome play-sets: a burgeoning crossbreed of consumerism and war play.

Despite early successes, Hasbro’s production of toy soldiers stalled during the Vietnam War. According to a Newsweek article, yearly sales of the original G.I. Joe line plunged from $22 million to $6 million during that unpopular conflict. As the war dragged on, the toy company billed G.I. Joe as a “man of action” rather than a soldier. Instead of battling Vietcong soldiers, our hero fought sharks, mummies, and other depoliticized enemies.

*

G.I. Joe rose from the dead in 1982, sporting a vivid cast of new characters. Taking cues from the wildly successful Star Wars toys, G.I. Joes shrank from foot-long dolls to 3 3⁄4-inch-long action figures. Cultural critic Tom Engelhardt studied this toy-soldier renaissance in his 1995 book, The End of Victory Culture. In a telephone interview, he fondly recalled visiting the Hasbro headquarters during the creation of a brand-new plastic army.

“They were all amateur military strategists—they had decided at that moment that the Russians weren’t going to work as an enemy. They were on to terrorism before Paul Wolfowitz and the other neocons. If you think about Cobra, it’s an amorphous terrorism organization. It’s not state-bound; it’s a superhero terrorist organization. I don’t want to claim that they saw the future literally, but in essence these guys did grasp the future—there wasn’t any money in the Russians.”

Just before launching its toys, Hasbro asked Marvel Comics to create stories for these action figures. Marvel picked Vietnam veteran and up-and-coming comics writer Larry Hama to handle the new series. Under his direction, the very first issue of the comic book jettisoned the pacifism, disarmament, and defeatism that had crippled the toy line during Vietnam.

The book opens with the Joes hoisting an American flag in the heat of battle—simulating the Iwo Jima flag-raising in pop art colors. In the first comic, the heroic soldiers rescue a pacifist nuclear scientist from her Cobra kidnappers. The peacenik doctor offers a curious apology at the end: “You risked your own lives to save mine. I had presumed so many horrible things about you… and the army,” she says. “At least I now know that somewhere in the Pentagon… there are people who care.”

According to Woods, the first year of production went amazingly well for the new G.I. Joes. The comic book sold 250,000 issues in good months, and the toys earned an estimated $40 to $50 million in that first year. More than fifty different companies bought merchandising rights to the G.I. Joe logo, which appeared on toys ranging from video games to kites.

The G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero television series ran from 1983 until 1987, continuing this toy-soldier invasion with bloodless explosions and laser-beam shootouts. Still, this animated violence concealed a training-wheels version of global politics.

In the episode “Let’s Play Soldier,” the Joes head to Thailand to foil Dr. Mindbender’s attempts to market a mind-control drug as chewing gum. One generation before, similar anxieties that Communism would spread throughout Asia ignited the Vietnam War. One of the G.I. Joes makes the connection more explicitly. Upon spotting some homeless children, he says, “Street orphans. Kids fathered by American soldiers during the war.”

That episode quietly revises the failures of the Vietnam War. With the help of these American love children, the Joes destroy Cobra’s mind-control factory. The orphans stay in Thailand, keeping G.I. Joe’s ideals alive in a region haunted by American aggression. After stopping the insidious spread of Cobra/Communist chewing gum, G.I. Joe returns home victorious from the jungles of Southeast Asia.

G.I. Joe’s epic advertising campaign peaked in 1985, when Hasbro had toys, cartoons, comic books, and countless merchandising tie-ins swamping the market. That was a historic moment for American culture. In a paper about war and culture, political scientist Patrick M. Regan estimated that 9.5 percent of all toys produced in 1985 were war toys—“the highest ratio of war toys to total toys outside of the World War II period.”

On a metaphorical level, the role of Dr. Mindbender and other G.I. Joe toys had also expanded. While the new comics still stoked kiddie consumerist impulses, they also delivered ideological medication—rehabilitating the image of the American military.

*

Out of all those G.I. Joes created in the 1980s, the good-guy soldier Dusty was best suited for contemporary wars. He debuts in issue 58 of the comics, engaged in a spectacular firefight between aging Russian tanks, Middle Eastern freedom fighters, and a G.I. Joe strike force. This hometown hero wears desert camouflage and face paint, and his head is covered with a leather aviator’s hood. After the battle, Dusty praises a pint-size insurgent perched on top of the burning tank: “In these parts, you’re a man when you turn thirteen. There were drummer boys younger than him at Gettysburg.”

The G.I. Joe comics embraced this kind of Reagan-era interventionism, visiting a number of political hotspots over the course of 155 issues: the Persian Gulf, Latin America, and Russian republics. One early story has our heroes delivering rockets to Mujahedeen guerillas as they battle Russian soldiers.

Larry Hama explained his focus on terrorism and Middle Eastern wars. “I could see that the day of the big land battles between super-powers was over,” he wrote in an email exchange. “It was going to be insurgencies and terror from now on. The big super-power slug-out, well, that’s just Armageddon, right? Terrorism and wars by proxy are what we have to deal with.”

In addition to the comics, Hama created meticulous file cards that Hasbro affixed to the packaging of each toy soldier. Some of these short, descriptive biographies were grounded in the real experiences of soldiers that Hama knew during his service. Dusty’s file card could be a description of many Americans in the all-volunteer military now serving in Iraq: “Dusty loves the desert. It is clean, pure and unforgiving. Unlike Vegas which is always willing to give you a second chance. Dusty was working as a refrigerator repairman and studying desert ecology at night when his pre-enlistment application for the G.I. Joe Team was approved.”

The G.I. Joe TV cartoons had a similar fascination with desert warfare. In the “Cobra Shockwaves” episode, the terrorist group attacks oil reserves in an unnamed Middle Eastern country. Then, in “Cobra Stops the World,” they hijack the entire world’s oil supply in a series of coordinated attacks. While G.I. Joe averts both catastrophes, Cobra Commander always escapes in the last scene. These obligatory getaways ensured more episodes, but they also reinforced a new kind of political narrative.

In his book, Tom Engelhardt uses G.I. Joe to explain how Saddam Hussein became a lightning rod for American wrath: “[The] jerry-built nature of the ‘enemy’ in the Persian Gulf War would be particularly striking,” he writes. “Saddam, like the COBRA commander, would enter the home via the TV screen with instructions in place, while the Iraqis would become a nation of no-traits in the blankness of their country.”

Cobra Commander became the new face of evil: a terrorist without national boundaries, magically detached from any civilian population. With that new kind of enemy, the G.I. Joe franchise’s metaphorical mind-control program took on a whole new function—preparing a new generation for twenty-first-century conflicts.

*

Following Hasbro’s lead, the U.S. Army recently created its own version of a desert action figure—immortalizing a real-life Iraq War veteran with his own toy soldier.

“Some kids grow up and they just know what they want to do,” army sergeant Tommy Rieman said in an interview. “I always wanted to be a soldier at some point, and G.I. Joe had a lot to do with that. It’s what they did—they were fighting for something good, something right—and they looked cool doing it.”

Released in toy stores last year, Rieman’s action figure is dressed in desert fatigues and a bulletproof vest. Perpetually mounted on a plastic strip of desert landscape, his inflexible figure points a rifle at invisible enemies. Along with eight other veterans, Rieman is celebrated in America’s Army Real Heroes program—part of a multimedia recruiting program for the U.S. military.

The flashy America’s Army web page allows kids to explore Rieman’s biography, see his high-school football pictures, and read accounts of the horrific 2003 ambush that nearly killed him in Iraq—a digital version of Hama’s G.I. Joe file cards. The “America’s Army: Real Heroes” slogan is a near-anagram of G.I. Joe’s “Real American Hero” trademark: close enough to remind teenagers of the toys they loved, but different enough so the army could reclaim its brand from a bunch of toys.

But the crazy thing is that the army didn’t need to repair its image. Dusty and G.I. Joe had already purified the army for a new generation, scrubbing away the shame of Vietnam. G.I. Joe had been selling desert warfare for decades.

When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August 1990, he initiated the first war that the G.I. Joe generation had ever seen. That same month, King Fahd of Kuwait asked for U.S. aid to combat the Iraqi invasion. The American attack began in January 1991—a ground battle punctuated by high-tech airstrikes. A cease-fire was declared by the end of February.

The G.I. Joe comic book appropriated these events as fast as a monthly news magazine. The February 1991 issue recounts how Cobra teamed up with a fictional Middle Eastern leader to invade a nearby country called Benzheen. “What a coup! Benzheen sits on top of 10 percent of the world’s oil. And now Cobra owns it,” one bad guy cheers after the invasion.

In the next issue, the Emir of Benzheen begs America for ground support in his besieged country, and G.I. Joe comes to the rescue. Numerous gun battles were carried out through pinkish night-vision goggles, mimicking the footage of tracers, Scud missiles, and smart bombs that had filled the real-life newscasts. The first video-game war fit perfectly into the pages of a comic book.

Nevertheless, this fictionalized Gulf War includes a disproportionate amount of G.I. Joe casualties. In all, eight soldiers die during that conflict—a massive toll for a toy line with a cartoonish relationship to death.

Hama invests Dusty with the darkest role in this Gulf War–inspired saga. After a Cobra sniper kills his war buddy, Dusty recalls the Christmas dinner that he shared with his dead friend’s family. “My brother was in Vietnam,” his partner’s mother had told Dusty. “His unit was overrun. He was listed as missing in action… we never got the body back or anything.” Dusty carries her son’s corpse out of the desert, redeeming the failures of Vietnam in a grim, patriotic moment.

Compared to the real Gulf War, the comics series ends on a mournful note. The battle concludes when another soldier orders Dusty to stop fighting. “Cease-fire—nobody won. The Emir made a deal with Cobra Commander,” he explains. “Cobra is pulling out and the Emir is pulling out the welcome mat from under the Joes.” The G.I. Joe comic book never shows the ticker-tape parades that followed the end of hostilities in the desert.

But Larry Hama got it right. He knew that Dusty the desert trooper wasn’t finished fighting. In another ten years, some of the kids who read that series would end up fighting a new and bloodier war in the Middle East. Impressed by his work, Idea and Design Works (IDW) Publishing hired Hama to relaunch the G.I. Joe comics series this fall. Hama hinted that his new series will reflect the darker realities of contemporary warfare. “Cobra will be a lot less benign in the IDW iteration,” he explained. “The gloves are off.”

*

“The way things look I’ll be driving a vehicle in Iraq that any boy who ever watched G.I. Joe could only dream of,” muses Jason Christopher Hartley in his memoir, Just Another Soldier: A Year on the Ground in Iraq. Hartley’s 2006 book recounts his National Guard service during the Iraq War.

Hartley is tall, skinny, and tough; a foulmouthed sarcastic streak runs through his memoir. The America’s Army recruiting website seems earnest and quaint compared to his manic prose. In addition to his memoir, Hartley cowrote Surrender, a performance-art piece about the Iraq War. Both these works dig into the gleeful, bloody, and decidedly unheroic side of G.I. Joe—a brand that celebrates the seemingly paradoxical impulses of heroism and bloodlust.

Earlier this year, Hartley workshopped Surrender in a small Manhattan theater, dressing the whole audience in desert fatigues and guiding them through a weapon-training simulation. He armed patrons with replica rifles and taught them how to steady the buttstock on their shoulders. Taking turns, each audience member crept across the stage like a kid playing backyard G.I. Joe games—learning the simple, anxious mechanics of what patrol troopers do in Iraq every day.

Hartley had the most candid view of the relationship between war play and recruitment. “Movies and video games are the lexicon of soldiers,” he explained. “It is literally why most of us joined—we just wanted to extend the excitement into real life. Even after all the violence we saw—something that has affected me profoundly—these games and movies and my job in the army are still just as exciting as they ever were, except now there is this weird psychological addendum to it all where my brain says, ‘But this is all actually quite disturbing.’”

After each simulation, Hartley explained how many of participants would have died during the actual maneuver. During the Surrender workshop, participants could actually feel the real, twitchy madness of Iraq—quickly learning that most civilians make lousy soldiers.

Larry Hama elaborated on recruitment in an email exchange about the G.I. Joe comic books. “War is bad,” he wrote. “To some it will be the most exciting thing they will experience in their entire life. To others it will haunt their nightmares forever. Don’t make a choice based on reading fiction (especially anything I have written!).” G.I. Joe helped children rehearse the motions of war in the 1980s, but it could never make them good at it.

*

Earlier this year, Paramount Pictures released a publicity photo of Snake Eyes from the live-action G.I. Joe: Rise of Cobra movie, slated for a 2009 release. Encased in black leather and hidden behind a skintight mask, this mute ninja was one of G.I. Joe’s most iconic good guys. In the upcoming film, he will be played by Ray Park—the swashbuckling actor who starred in Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace as the evil Jedi Darth Maul.

That image generated hundreds of nostalgic web posts. On the most basic level, Snake Eyes fulfilled the karate fetish that gripped many boys in the ’80s. Still, his character maintained a sophisticated, ambiguous relationship with the military in the G.I. Joe comics.

In the last issue of the G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero series, a teenager writes to Snake Eyes seeking enlistment advice. It is the perfect opportunity for the hawkish tendencies of the toy line to soar, but Hama takes a somber approach.

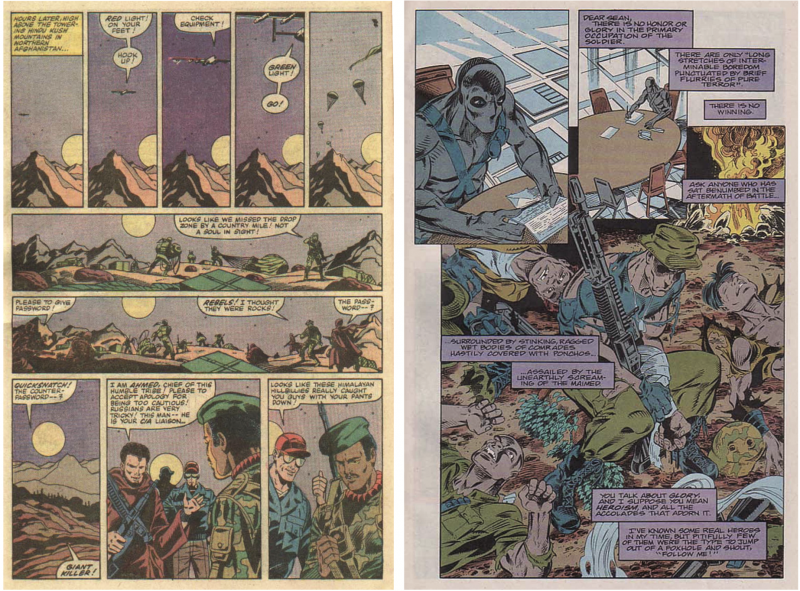

Snake Eyes responds with a letter about his experience in Vietnam. At the climax of the comic, the ninja crouches in a field of trampled flowers and dead soldiers, clinging to his enormous rifle like a life raft. “There is no honor or glory in the primary occupation of the soldier,” Snake Eyes reflects. “There are only ‘long stretches of interminable boredom punctuated by brief flurries of pure terror.’ There is no winning. Ask anyone who has sat benumbed in the aftermath of battle… surrounded by stinking, ragged wet bodies of comrades hastily covered with ponchos… assailed by the unearthly screaming of the maimed.”

That eerie passage had a lifelong influence on Major Philip Kost, a G.I. Joe aficionado and career soldier. On the Internet, Kost curates the five-hundred-plus membership on the G.I. Joe Reloaded discussion board. Most recently, he worked as military consultant for Devil’s Due comics—the company that revived the G.I. Joe franchise in 2001.

Kost told me that he returned to Snake Eyes’s letter over and over during his service. “I can understand it better now. [Larry Hama] laid it out there on the line. The intent of the letter was not to glorify anything or detract from anything. It was to tell the truth. This is how things will be if you take this route. Don’t think it’s all going to be glory and honor, but on the other side, it’s not the worst thing in the world either. Here it is, make your decision.”

Kost and Rieman and Hartley all played war, but they were never brainwashed. They knew exactly what they were getting into before they enlisted, because G.I. Joe taught them. Even as this brand revived the military’s image, American failures and the grim realities of war haunted the issues. Like a secret code embedded inside the heads of ’80s kids—Dr. Mindbender’s revenge, if you will—the inscrutable ninja named Snake Eyes ended nearly a decade of military worship with a sermon about the nightmares of combat.

It’s easy to rebuke Hasbro for kindling warlike impulses in innocent minds. But that critique treats childhood like some Garden of Eden, miraculously isolated from adult hostilities. Children have never been peaceful. From the very first moment they shape a thumb and pointer-finger into a pistol or turn a stick into a sword, they are playing war. G.I. Joe taught children what that violence meant, helping them process the confusing legacy of Vietnam, the frightening conflicts of the Reagan era, and the unsettled conclusion of the first Gulf War.

Snake Eyes is the serpent in that peaceful garden, peddling apples from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil—a symbol that embodies both a curse and an enlightened intelligence. Next summer, a generation bewildered by the Iraq War will sample his forbidden fruit for the first time.