I wonder why no one thought of it before: The Nancy Book (Siglio Press), a collection of Joe Brainard’s oeuvre-within-an-oeuvre featuring Ernie Bushmiller’s Gioconda of the postwar funnies, produced in various media between 1963 and 1978.

I wonder if it’s worth saying right off that the Nancys are by and large less beautiful than most of Brainard’s art. Less, for instance, than the modestly ravishing pen-and-ink illustrations with which Brainard graced the books of numerous poet-friend-collaborators. (The Vermont Notebook, with John Ashbery, and The Champ, with Kenward Elmslie, are terrific examples.) Carter Ratliff calls Bushmiller’s own line “crisp but uninspired,” omitting how well it met the needs of mass newsprint reproduction. Brainard came to mimic it perfectly, when he chose.

I wonder if sustained discussion of the Nancys isn’t akin to explaining a joke. They’re so deft and likeable that calling their jibes at (mainly) sex and art history “critical” seems gravely misleading.

I wonder whether anyone needs reminding that Nancy herself was never such a raving beauty either.

I wonder how little biography we can safely get by with: Born in 1942, Joe Brainard was raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he was the town’s prize- and scholarship-winning art prodigy as well as, from age eight, his mother’s favored dress designer. With high-school poet-chums Ted Berrigan and Ron Padgett, he headed for New York City in 1960, where, within a couple of years, he discovered Pop and assemblage. By 1963, he had quietly but decisively come out as gay. Alongside his visual art, he wrote a fair amount of disarmingly un-“literary” prose, most famously the lapidary 1970 autobiography I Remember and its sequels. Increasingly uncertain about the merit of his work, he largely withdrew from exhibiting it publicly after 1976. He continued to split his time between the city and a country home in Calais, Vermont, with Elmslie until his death from AIDS-induced pneumonia in 1994.

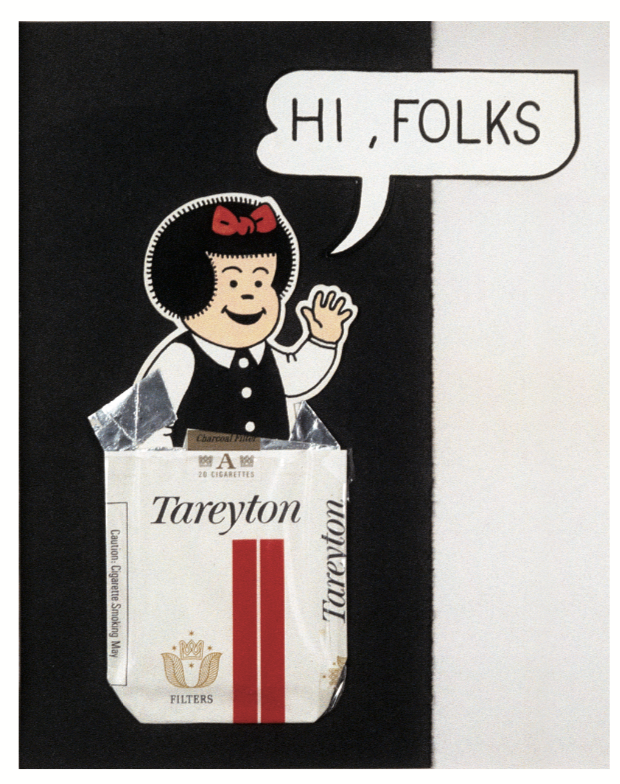

I wonder if the additional facts supplied (“Joe smoked Tareytons”) in Ron Padgett’s and Ann Lauterbach’s lucid and affectionate essays are a help or a hindrance to an audience who didn’t take the Tulsa Sunday World growing up or eat new peas with the artist in Calais.

(I wonder this as one highly susceptible to coterie-envy: I devoured Padgett’s 2004 biography, Joe: A Memoir of Joe Brainard, much as Padgett says that its subject devoured novels “for the pleasure of characterization.”)

I wonder why Brainard chose Nancy’s name for the subjects of two prose pieces, both from 1963, also included in The Nancy Book. Neither takes pains to accurately describe Nancy-of-the-comics. One has “a grandmother with an Italian sense of the dramatic”; the other, the narrator’s sweetheart, has “bright red lips” and “long black hair.” Both disappear in the stories’ closing paragraphs, in favor of details that would resurface in I Remember: “When I first started having erections, I didn’t know what they were.”

I wonder why—aside from a “sick” 1969 parody of a daily strip in which Nancy and Sluggo get hooched up while Aunt Fritzi is eaten by a dog—the other figures that populate Bushmiller’s world are absent from Brainard’s. (And what’s become of the celebrated “three rocks”?)

I wonder whether Sluggo, from off-panel, suspects that Nancy’s backdoor man is Carl Anderson’s oval-jawed “Henry.” Or so one gathers from the sticky ’toon coupling depicted in Recent Visitors (1971), a cross-universe Tijuana bible accompanied by Bill Berkson’s oblique captions (“In England, ‘wet’ means ‘stupid’”).

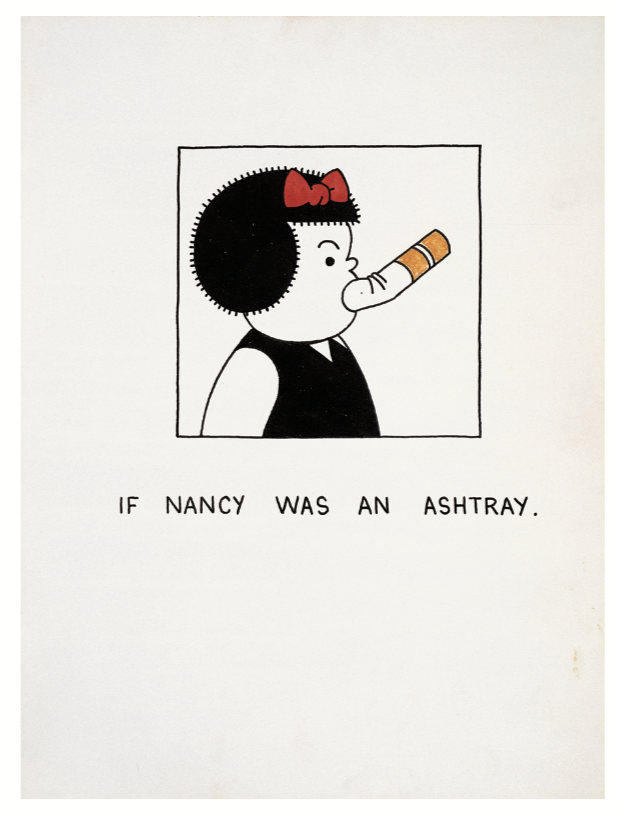

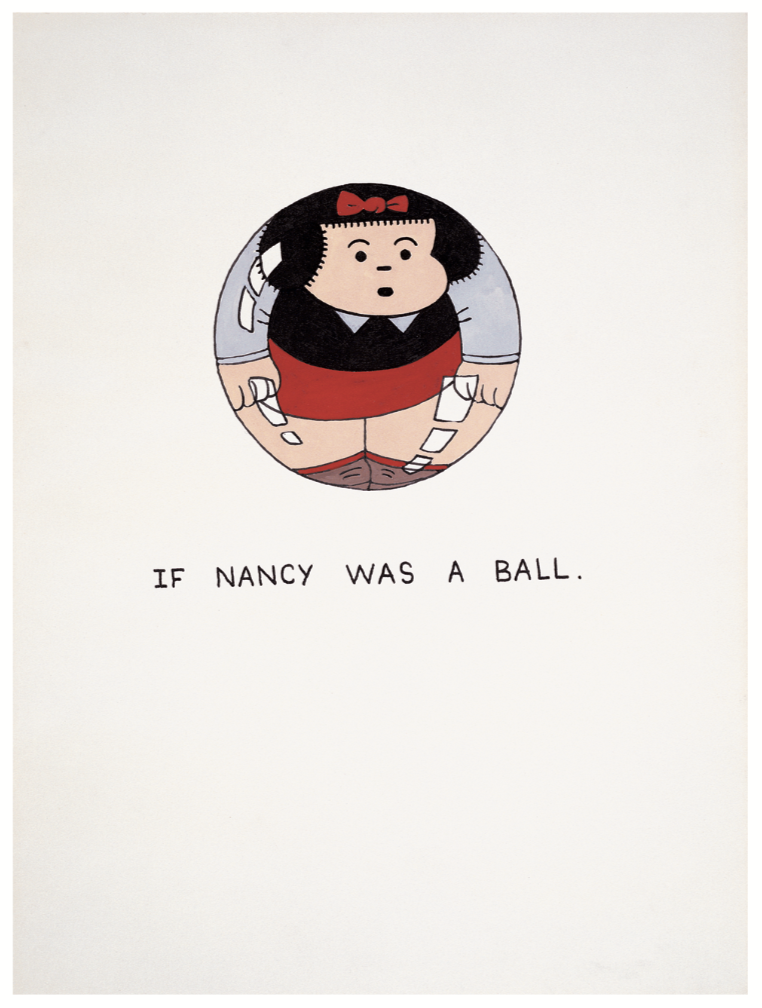

I wonder if Brainard didn’t tire of subjecting Nancy to this kind of abuse. In If Nancy Was (1972), a major suite of single-panel drawings and collages, sex is rarely far away. In If Nancy Made Blue Movies, her head is collaged onto a naked woman’s body in a stag-film ad (“TRI-SEX”) torn from Screw or something like it; in If Nancy Was an Underground Comic Character, drawn in a sub-Crumb hand, she frigs herself silly. But now the joke is less on Nancy’s soiled innocence than on the harsh and numbing unsexiness of the forms adopted. Brainard’s own brand of candor, less aggressively subversive, comes through in works drawn in Bushmiller’s manner: If Nancy Was a Boy, If Nancy Knew What Wearing Yellow and Green on Thursday Meant.

I had wondered if Nancy’s creator, who worked on the strip into the 1980s, ever saw Brainard’s work, until I checked Padgett’s biography. When he tried to buy some original art, “Joe was disappointed that the great cartoonist did not respond—until somewhat later, when Bushmiller got wind of Joe’s Nancy works and threatened to sue him. Oh well.”

I wonder if Brainard gave much consideration to the fact that both the twenty-four panels of If Nancy Was and the hundreds of disparate observations that make up I Remember are organized and to some degree generated by their respective grammatical structures:

I remember putting on sun tan oil and having the sun go away.

I remember Dorothy Kilgallen’s face.

I remember toreador pants.

If Nancy Was an Ashtray

If Nancy Was a Ball

If Nancy Was the Bright’s Disease

(Who but a pedant would point out that these titles ought to run “If Nancy were”?)

I wonder if Brainard imagined that one of his hypotheticals would someday become actual, more or less. If Nancy Was Abraham Lincoln seamlessly affixes her profile to Lincoln’s shoulders at the scale of a genuine, visibly canceled four-cent stamp. In 1995, the year after Brainard’s death, Nancy and Sluggo were among the “Comic Strip Classics” honored by the USPS.

I wonder if Brainard’s method in the If Nancy Was panels—which consists in the perfect realization of their one-line captions—is so distant from what comic artist/theorist Mark Newgarden, in his essay “How to Read Nancy,” calls Bushmiller’s “relentless pursuit of the gag.”

I wonder just how to distinguish Newgarden’s own deployments of Nancy from Brainard’s. In “Love’s Savage Fury” (1986), Newgarden mobilizes her pupil-less eye-dots, coin-slot nose and mouth, hair-nubs and bow as a concrete poet might the alphabet. Mr. Potato Head and Wooly Willy come to mind: Nanc-emes shrink, grow, and shift across her face, eventually breaking loose and multiplying like protozoa in the panels’ white space. Brainard sometimes engages in such permutations: If Nancy Had an Afro is one inevitable and rather mild distortion. More often, she remains an unfissionable particle, stubbornly herself through global transformations of style, topology, or context.

I wonder if the difference isn’t just this: Newgarden means to increase the gravity, or at least the self-consciousness, of our encounters with “graphic literature,” while Brainard would lighten the atmosphere surrounding “modern art.”

I wonder what Bushmiller would make of Nancy’s present incarnation, written and drawn by Guy and Brad Gilchrist. In the daily strips I’ve paged through online, Nancy’s resilience has become dispiritingly mindless. (When blue, she says, “I just pretend to be happy till my brain catches up.”) And her form has taken on that uncanny roundedness common to legacy characters in the age of digital graphics. (Have you seen the Campbell’s Soup Kids lately?)

I wonder why, for all his facility in multiple media, Brainard took the equation “great artist = great painter” so much to heart. In 1967, he wrote, “I can see myself as a Cornell or a Man Ray, but somehow I doubt that I’ll ever be a De Kooning or an Alex Katz.” Though a 1974 show of oils, including Nancy Diptych, was not his final solo exhibition, its cool critical reception and his own dissatisfaction accelerated his self-imposed retirement.

I hardly have to wonder if Nancy was in part a weapon for Brainard, against both the burden of art-historical “greatness” and his own ambitions toward it. There’s a “Picasso Nancy,” a Larry Rivers, and several De Koonings (though no Katz). In the well-known cover collage for the 1968 Art News Annual, Nancy intrudes, Waldo-like, on a textbook’s worth of masterpieces, modern and otherwise; she darts from “behind” one Mondrian square into another, while her head replaces those of Manet’s Olympia and every figure in a Rembrandt grouping.

I wonder whether there could be any more precise measure of how seriously Brainard took art than these works’ serial iconoclasm.

I wonder if Brainard would have found any comfort in Mel Bochner’s unpublished review of the 1969 Whitney Biennial, commissioned and rejected by Artforum. “I do not believe that painting for its own sake rates automatic credit as the sole means of making two-dimensional art…. The special place of painting in art is only by weight of consent.” Probably not: Bochner’s complaint was with the omission of work coming out of Minimalism and Conceptualism, movements of which Brainard wrote, that same year, “I suspect that years and years from now people are going to find themselves stuck with a lot of snotty art.”

I wonder, though, if the Nancys aren’t more “conceptual” than they appeared at the time, with their emphasis on text-image relationships, reliance on a generating grammar, and querulouslessness toward sensual engagement. Much of Brainard’s output, as I’ve said, pursues beauty; Nancy allows him to hold it at arm’s length. She never looks more absurd than gussied up with wig, beauty mark, and cleavage in If Nancy Was a Sexy Blond (which could as well have been titled If Nancy Went Camping).

I wonder whether a prose fragment not included in The Nancy Book—“Pat,” nominally a portrait of Ron Padgett’s spouse—doesn’t come closest to describing the Nancy that Brainard saw, and showed: “It seems to me that what she is is based totally on herself, and nothing else.”