1.

The first victim of the RMS Titanic died in 1910, two years before the ship sank. This was Samuel Scott, an Irish shipyard worker who fell off a ladder into the open hull and fractured his skull on impact. He was a teenager, earning roughly five dollars a week. The last Titanic death came a century later, in 2009: Millvina Dean, who died of pneumonia in England at the age of ninety-seven. She was a passenger on the ship as an infant; her father was coming to America to open a tobacco shop in Kansas City, Missouri. He lowered Dean into a lifeboat in a canvas mailbag, stayed behind, and drowned.

It’s possible to think of the Titanic not as a disaster that lasted a single night, then, but as a disaster spanning generations. Or, more than that, as one of our greatest cultural embodiments of the idea of disaster. This is how Walter Lord, dean of Titanic historians, came to think of it after decades of research. He wrote: “The thought occurs that the Titanic is the perfect example of something we can all relate to: the progression of almost any tragedy in our lives from initial disbelief to growing uneasiness to final, total awareness. We are all familiar with this sequence and we watch it unfold again and again on the Titanic—always in slow motion.”

Initial disbelief, growing uneasiness, and final, total awareness. This is how it feels when a ship sinks.

2.

When the boat first hit the iceberg, several tons of ice broke off onto the starboard well deck. Passengers were delighted, and began staging snowball fights and kicking the chunks around like soccer balls. It became a kind of scene. “Would you like a souvenir to take back to New York?” asked the prizewinning horseman James Clinch Smith, holding out pieces of the ice to a group of other first-class passengers. The seaman Walter Hurst woke up sharply when his father-in-law tossed a lump of the ice into his bunk, as a prank.

The editor W. T. Stead, who has been called “the foremost publisher of paperbacks in the Victorian Age,” and who frequently communicated with the dead through spiritualist mediums, emerged from his room to ask about the source of the commotion. “Icebergs,” replied the painter Frank Millet, not looking up from his card game. Stead shrugged and went back to bed.

3.

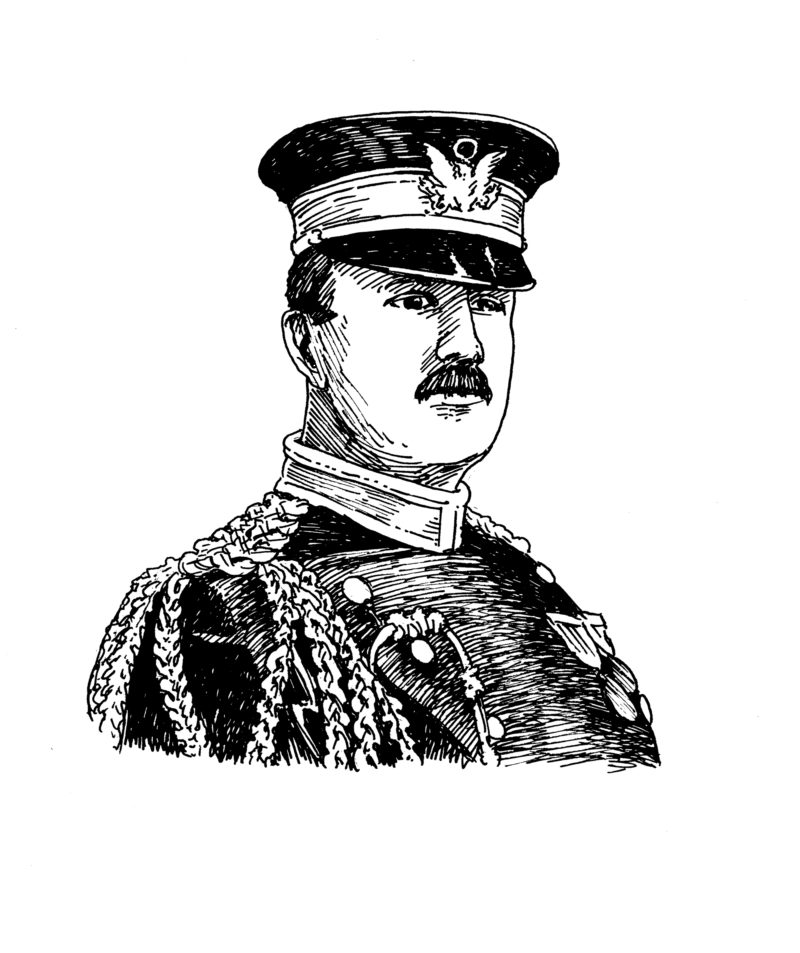

To President William Howard Taft, the most notable casualty of the Titanic was a person named Archibald Butt. “He was like a member of my family,” Taft said in his eulogy, “and I...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in