1.

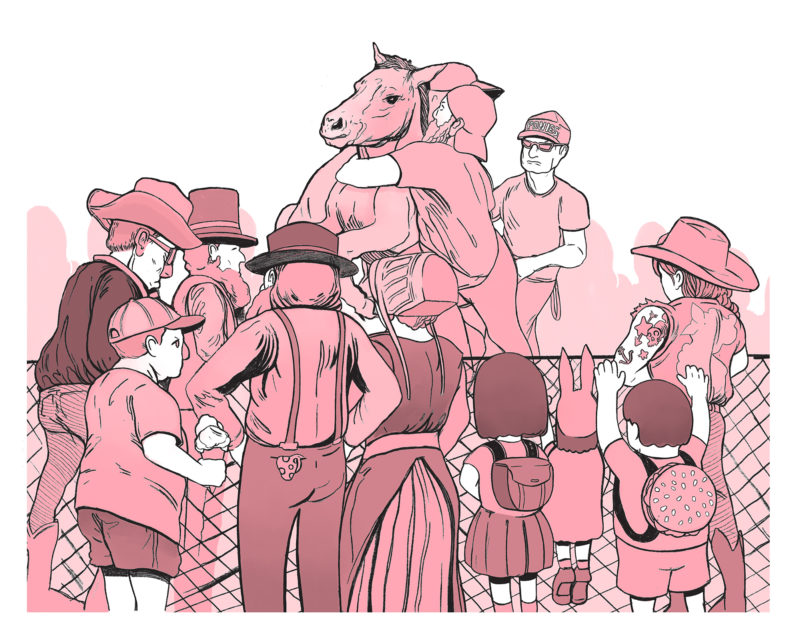

Just before dawn on a late July morning, I stood next to a Mister Whippy ice cream truck with a throng of people looking out over a swamp on the far eastern shore of Virginia. We were weighing our options. In a couple of hours a herd of wild ponies would thrash through the water and climb ashore on the other side of the swamp. A small group of people already stood there, on a strip of solid land. If we joined them, we’d be closer to the ponies, close enough to see their nostrils flare above the waterline as they pawed their way across; close enough to stroke their manes once they made landfall. We’d get to shake hands with the Saltwater Cowboys, the fraternity of wranglers who convince the ponies to swim. Every summer the cowboys round up the foals and mares on the barrier island of Assateague and swim them across a channel to the touristy island of Chincoteague. The ponies are then paraded through the winding streets to the island’s fairgrounds, and are auctioned to fund the volunteer fire department.

Not everyone who came to the Chincoteague Island Pony Swim crossed the swamp; there were other places to watch the event. Some in the crowd chose the comfort of the nearby Veteran’s Memorial Park, which was outfitted with jumbotrons and a sea of camp chairs; others stayed near the Mister Whippy truck and watched the landing through binoculars. Crossing to the far side of the swamp is for the diehards: pony swim veterans, little kids who have made their parents wake up early, as if it were Christmas morning, and horse-loving grown-ups like me who want to see something they’ve been imagining since they were ten.

The swamp, a pit of black muck, stinking of sulfur, was bordered on one side by a giant pier reserved for press photographers, and on the other side by a complex of ugly, vinyl-sided condos with a strictly enforced no-trespassing policy. I stood next to a woman from Cincinnati who was engaged in a debate with her eight-year-old daughter about whether or not to cross. The girl had liked the idea in the abstract, but now she wasn’t so sure. I understood how she felt.

“Did you read the Misty books?” I asked the girl, referring to Misty of Chincoteague, the children’s book by Marguerite Henry that forms the foundational legend of this place. Henry came to the pony swim in the mid-1940s and wrote a book about a small foal she met, and eventually bought, called Misty. The girl, clinging to a stuffed pony, nodded yes, and looked up at me. “So did...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in