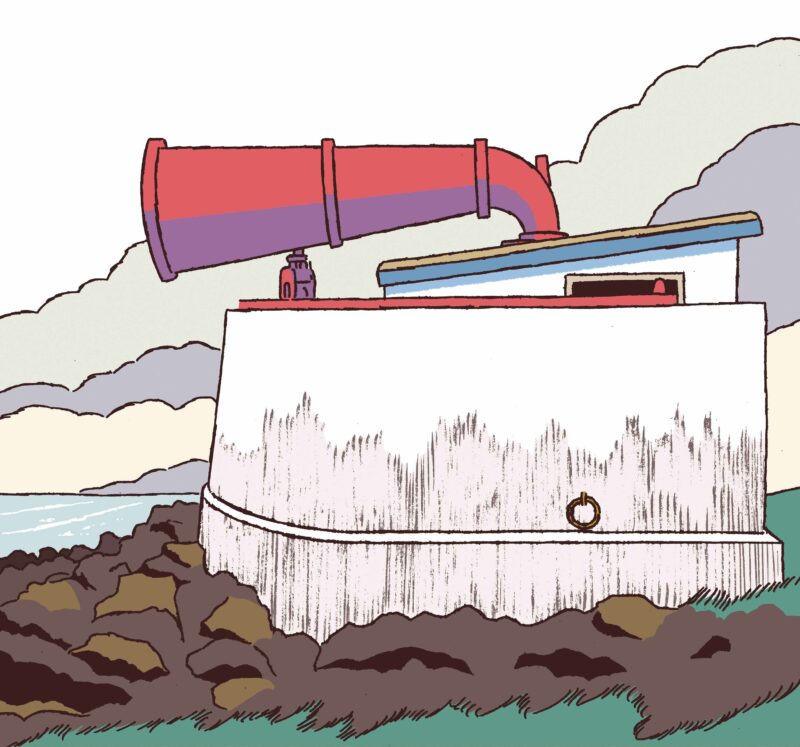

FEATURES:

- Does not resemble anything human

- Soothing

- Barely attenuated by fog

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in