I. WWDD?

After I read his memoir, Half a Life, I mentioned to the author Darin Strauss that I was thinking about writing about my “thing,” the way he wrote about his “thing”—the one thing that defines most of us (whether determined by others or by ourselves). He wrote me this: “As for what you write next: if you don’t want to write that, don’t. It seems wildly personal, and so if you feel uncomfortable, listen to that. This book took twenty-eight years for me to even start. But thanks for being so nice about it.”

So What Would Darin Do? He managed to wrestle his thing out of himself. But he also said I could wait on my thing. Or not do it at all. Somewhere therein lay perhaps just the permission I needed to type, or not type, the roman numeral I above, and begin to find out whether I even could.

I don’t really want to write about this thing of mine, but I think I might have to—to stop it from being my thing. If that’s possible. I could certainly regret it later, like I’ve regretted candor on a few distinct occasions in the past.1 It’s just that nowadays, one’s candor and the resultant exposure can end up hanging around forever for people to pick through. My kids, for example, who in five or ten years can and probably will get on the Internet to read all they can about the subject. One Google search, and something my wife and I have taken great pains and sensitivity and a bunch of time and effort to explain and share with them in the safe, accepting, and loving environment of our household could be unraveled in an instant. Because when one’s candor is filtered through another human being, especially one with a little more power,2 the results can be devastating. So I suppose this essay is an attempt to be my own filter, leaving me nobody to blame but myself when it all goes pear-shaped.

Well, me and Darin Strauss. A difference being, his “secret” (at eighteen, having been involved in an auto accident that left a teen girl dead) was something he could (and did, successfully) hide for many years after leaving home. I cannot reliably hide that I was not always the man I am today. Certainly, when I meet people for the first time, most do not know my “secret” (or, more accurately, my past, which many confuse with a “secret” if they’re not being told all of your business immediately upon making your acquaintance). But there will always be people whose history has paralleled and intersected my own—from family to colleagues to that girl Annika in the second grade who ate powdered soap at recess—and without a complete name-change and renunciation of my entire history (something I’m unwilling to do, as tempting as it sounds sometimes), it is nearly impossible for me to live completely stealthily as a man in this world, because, simply, I was not born male. Not in any conventional sense, at least. Not according to science.

II. Draft of a Letter to my Parents that I Contemplated Publishing in a Men’s Magazine

Dear Mom and Dad,

I know this is going to be a complete shock to you, not to mention a huge disappointment, but there’s something

I have to tell you, and I hope you’re sitting down.

I’m not gay.

There, I said it. It’s out there, and I can’t take it back.

But before you start freaking out, I want to give you the good news. Not only am I not gay, but I’m so not gay that I’m engaged to be married, plus am now a stepdad to my fiancée’s two beautiful blond children. We all live in a nice four-bedroom, two-and-a-half-bath house, and have two hybrid cars, two rescue pit bulls, and a gray and white cat that I don’t like very much.

It’s everything you’ve ever wanted for me! I do yard work. And carpool. I’m completely normal, as in, there’s nothing you have to be embarrassed about with friends and family anymore—no more peroxided buzz-cuts, no faux-hawks or combat boots, no bringing home anarcho-vegan dates with septum piercings. No more homo anything at all! So you can just send those PFLAG brochures back to be recycled for somebody who actually needs them.

But there’s also some bad news, and I suppose I should share that with you, too. I know it’s not really cool that you’re finding all this out about me in the pages of a magazine, but, to be completely honest, for years I’ve been worried you’d reject me for not being gay, and terrified that you might decide to cut me out of your life completely. But you raised me to tell the truth both to myself and to others, so in that spirit I feel as though I need to “come out” to you even more explicitly:

I am a heterosexual man.

Let me take you back. Remember how good I was at football? Like, really good? How I was riding motorcycles at an age when most kids were learning to bicycle without training wheels? And how you had to promise me several pairs of shorts and pants in exchange for buying one gauzy dress to wear to Spencer Presler’s bar mitzvah? Or flash forward a little, to 2002. Mom, remember when you came to one of my readings for my first book, and there was a big poster with my picture on it, and it repeatedly referred to me as “he”? You seemed very alarmed and notified the bookseller of the “mistake,” but you never mentioned it again. Or, Dad, that time years before that, when we were out at a restaurant in Santa Fe, and you thought I was the maitre d’ and asked, “Sir, when will our table be ready?” I just said, “Dad, it’s me,” and you chirped, “Oh,” and then we sat down and enjoyed the rest of our Tex-Mex dinner?

Or let’s get even more contemporary. A quick Google search will yield ample evidence that your beloved daughter isn’t so much a daughter anymore. As an author, I’m fortunate to have my work mentioned or appear in various media, and you might’ve noticed that nowadays those media refer to me as “he.” For a couple years there, there was no gender pronoun, and other times, like in the New York Times Book Review, a writer will go out of her way to make sure that her audience knows “T is a she” (the reviewer was wrong, but whatever3). Either way, I know you’ve seen a lot of this stuff, because you’ve always been supportive of me and my work and you enjoy sharing in it. But I guess what I’m getting at is whether this news is even really a surprise to you at all.

I’m not quite one of those “born in the wrong body” types you see on Oprah or TLC. I actually think I was born in the right body, my body. It’s just a little different, and doesn’t fit squarely into the gender binary. But I think you’ve suspected that all along. You of all people, in fact, have known about the kind of kid I was, and the kind of person I’ve grown up to be: mostly well intentioned and seeking to do right by others, moderately creative, often stubborn, but generally pleasant to be around. I haven’t been tortured or miserable or beaten senseless on the playground because of my life experience—in fact, quite the opposite. It hasn’t always been easy (there was the time on the subway at knifepoint), but, for the most part, I’ve been quite lucky.

In truth, the most pain I’ve had over being a straight guy comes from my fears about how you would react. I can’t front and say I haven’t daydreamed about you dying before I’d have to explain all of this to you (because it would, of course, kill you anyway). So you can see why coming home for the holidays might be a little tricky this year. There’s my mustache, for starters. Then there’s the fact that my children know me as their stepfather, and they won’t know who you’re talking about when you continually call me your “daughter,” rapid-fire repeating it to anyone and everyone as though the more it’s said, the more it might go back to being true.

You no longer have a daughter. But you do have granddaughters. And they really want to meet the people responsible for making me into the kind of person who figured out that he wasn’t what others decided he was, evolving instead into something else entirely.

Love,

T

III. Excerpts from Various Drafts of the Letter I Eventually Sent My Parents

…I don’t think it’s a big mystery to you that I don’t identify as female. Sexual identity and gender identity are two entirely different (though of course not completely unrelated) things. I know for years you’ve just assumed I was gay—because of who I’ve been romantically involved with. But it’s not as simple as that—in fact, I don’t think I ever actually “came out” to you as anything, sexual-identity-speaking. I was just me, and this was who I was dating at any particular time. In fact, I never really felt gay at all, and that’s why those words never came out of my mouth. Not once. And the word lesbian? I have never and would never use that term in reference to myself. Never. In fact, I’m probably one of the most lesbo-phobic people on the planet, because of my own fucked-up issues of not wanting to be assumed to be one. I’ve got no beef with lesbians; I’m just not one. I’ve never seen even one episode of The L Word. Never been to the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, don’t even know who Dinah Shore is, and certainly never donned a thumb ring or ear cuff….

As far as my gender goes, I know it’s been obvious to you for years that my gender presentation is not normative, that is, it has never really fit perfectly into the male/female binary… it’s always fallen somewhere in between, and, in the past decade or so, it has organically migrated to the male side of the spectrum. I don’t know how else to say it, but: I’m basically a dude now….

I love you and always will. This has nothing to do with you, anything you did or didn’t do. I’m the same person I’ve always been, regardless of gender, or who I sleep with, have relationships with, what my haircut looks like, books I write, where I live, who I socialize with—anything along those lines. I am not “a man trapped in a woman’s body.” That’s asinine. I was born in the body I was born into; I’m not trapped, but I am a man. I know you’ve heard me say stuff like this in the past, both publicly and privately; I know you’ve seen some of this material pop up in some of my writing, at readings in the form of questions from the audience about my characters, or in interviews. I know you have been with me when people refer to me as “he,” and you have flustered many a waitperson when referring to me as “she” or “my daughter” when there is nothing but what looks like a son sitting at the table next to you….

If you can, please try to hear me, and not what you might’ve seen or heard on this topic; it’s not like the pregnant man on Oprah, or the lady on Maury who didn’t know she’d married a guy who had not been born male. It’s not like you’ve read in your PFLAG pamphlets, or online, about “roid rage.” I don’t turn into the Incredible Hulk at intervals (if only). I have not been tortured and miserable for years and years, and hiding some deep, dark secret that I’ve been afraid would come out and destroy me and my family; my experience is completely my own. It’s not a “hard life,” certainly not harder than most others on this planet. I know this may be forever impossible for you to understand, but this is nothing for you to worry about: it’s simply, for me, the most natural thing in the world.

IV. Sometimes I Think the Whole of Modern History Can Be Explained by Testosterone

There have been some new truths, even if they are also stereotypes:

(1) I don’t cry as much as I used to. Or: it takes way more to make me cry.

(2) I am angry more frequently. Or: it takes way less to make me blazing mad.

(3) I don’t get as bummed out by things as I used to. Or: my mood is generally positive.

(4) I have less patience.

(5) I am not as adept at communicating.

(6) I want to have relations with my wife, all of the time, regardless of context.

(7) People defer to me more.4

(8) I am stronger.

(9) I have more stamina on the treadmill.

(10) I say less to strangers.

V. A Brief Interview I Did for Esquire’s “How to Be a Man” Issue, from which My Answers Were Excluded in Favor of Insights from Nick Tosches and Tom Cruise Instead

ESQUIRE: What’s the greatest example you know, or have witnessed, of someone stepping up as a man?

T COOPER: The first example that comes to mind is pretty much anything Johnny Weir does. Outside that, honesty always leaves a big impression. Across the board, across gender, the bravery required to be completely honest with both oneself and with others is something that is as rare as it is great. So, to me, “stepping up and being a man” is twofold: it means trying to be as honorable as possible, and, in cases where you fail to be as honorable as possible, then it means to be completely honest about that shortcoming—without being mean or punitive. It’s more about being an adult than being a man.

ESQ: What about manhood do you know now that you wish you’d known at eighteen?

TC: (1) That men aren’t right all the time, or even most of the time.

(2) That men don’t have to act like they’re right when they know they’re wrong: except in bad movies, nothing is ever lost by admitting you’re wrong.

(3) That you can still be a man even if you don’t have a manhood.5

ESQ: What’s your favorite thing about being a man?

TC: Just “being a man” is something I can’t take for granted, since I was not born a man. But you know what? It turns out nobody else is born a man, either. Sure, roughly half of us humans are born male—but only a fraction of that fraction grow into men.

So I’d have to say my number one favorite thing about being a man is being a man. Because it wasn’t something that just happened to me. I had to work for it—going against what the world was telling me I was ever since I was pushed out of my mother and into it.

Other favorite things about being a man include (in no particular order): my sideburns, my sex drive, not feeling paralyzed with worry about everyone else’s feelings all the time, and the unconditional acceptance from and love of the best woman in the world, which have probably made me more of a man than any of the other shit out there—including testosterone.

VI. The Closest I’ve Ever Come to Writing a Poem, Not Counting Being Forced to Do so in Grade School

Fear6

She has me stripped and flayed and is swinging at will from the inside of my ribcage as if on one of those geodesic playground apparatuses. Primary-paint colors and rust flakes in her hands, she’s free-climbing all limbs and laughs and smiles, and we are both eight and eighty years young, and we are also unicorns riding clouds and cotton-candy kittens, and every puppy who ever fell in love with a wiry tomboy’s skinned knees. And the air is perfect even if the walls are rattling and cells are dividing and then (somewhat hauntingly) regenerating, only with her DNA in them.

And sometimes—in fact most times, if I’m honest—when she leaves whatever room I’m in, I am instantaneously seized by the distinct notion that she might never come back. Not ever. And not quite seized, rather more like doubled over in the driver’s seat in long-term-parking row 14A, the minutes just about to click over into another day’s rate, mouth carved into a grotesque howl, the sort where no sound comes out but the hiss of compressed air. And, to be further honest, it’s not only when she leaves the room, but generally any time her eyes leave mine (to drive, to walk, to read, to see something else).

There it is, the signpost up ahead: not the man she and the world need you to be.

VII. DREAM SEQUENCE

I feel pretty strongly that whenever writers write about their dreams in essays or memoirs, the dreams are vastly fictionalized. For obvious reasons. That said, and with full recognition that every story is altered to some extent by the retelling, I am going to attempt to recount faithfully a dream I had two nights ago: I was being harassed by a few policemen on a random street. When asked,

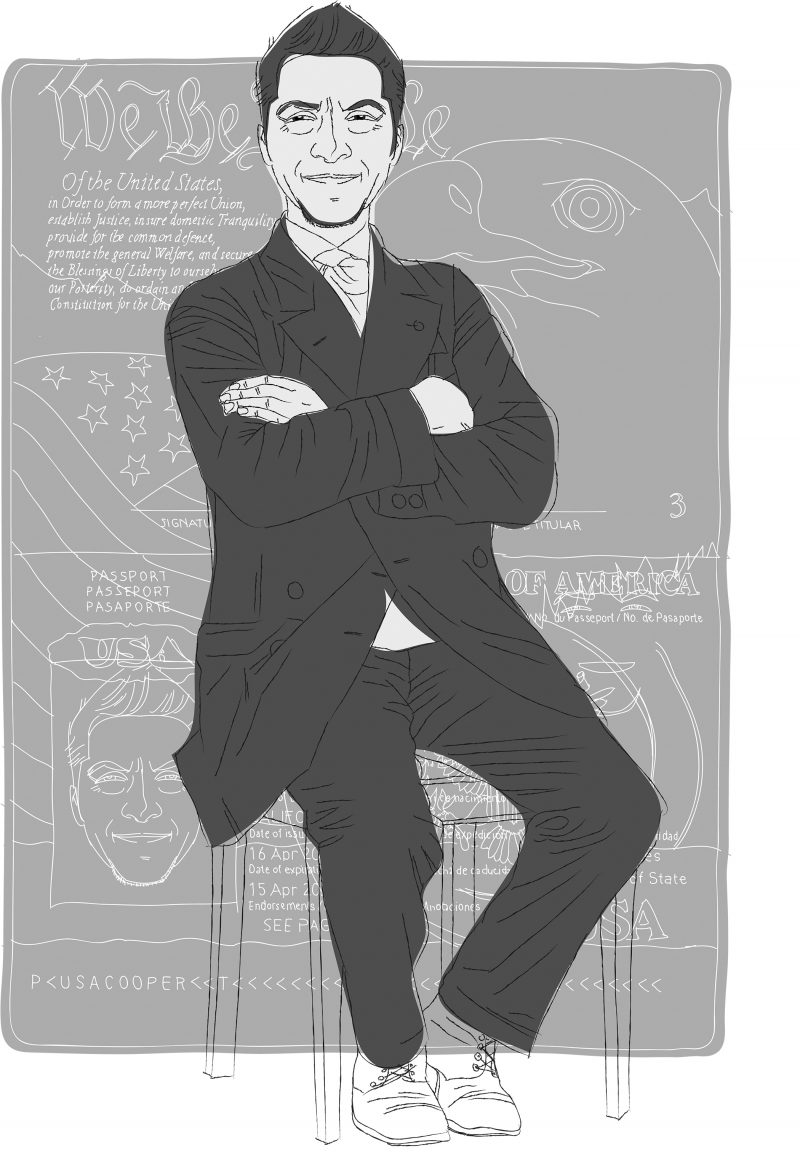

I showed them my driver’s license.7 While I was still pretty certain the policemen were going to let me go, I remember feeling relief that my paperwork was in order. I believe, but I cannot completely recall, that I was also asked to produce my passport,8 in addition to other random paperwork.

At some point I was suddenly arrested and taken into custody. I don’t know the cause, but it made some sort of sense to me as I was being loaded into an unmarked van with a bunch of other people (both males and females, all of us cuffed with hands resting in our laps) and driven to a prison that looked like a cross between San Quentin and every Midwestern prison you see on MSNBC’s Lockup. Outside the facility, we were joined by a few other vans full of prisoners, and as we exited the vehicles, we were all funneled into one line leading downhill toward the prison. After a dozen or so yards, a group of guards separated us into two lines—male and female—which fed into two different, side-by-side doors to the facility. I was put into the male line. I remember thinking all of it felt suspiciously like Buchenwald, but there was nobody to whom I might whisper the observation, as was my impulse.

The lines moved very slowly, and, for a time, the general atmosphere and my state of mind were calm. I didn’t question where I was, or fight it. I think I was feeling like I just needed to suck it up, serve my time, and then I would be free and all this would be behind me. It wasn’t like I was certain a mistake had been made, there had been grave injustice, or that I wasn’t supposed to be there (as usually is the case in my persecution dreams). As I inched ahead in line, though, and caught a glimpse of what was happening up ahead, I started to panic (only on the inside). There was a female guard with a rifle near me, standing between the two lines of prisoners, and I tried to get her attention. I was definitely the shortest and slightest guy in line. Nobody had paid me any particular mind before, but as soon as I started entreating the guard, a few people from both lines started to take notice, the way people get when somebody cuts in front of them at the movie concession stand. I coughed a few times until the female guard looked in my direction, at which point I tried to make my face really kind and open, to entice her to come over. She appeared at first impassive, but then it seemed like she might be wavering. I assumed she would ultimately decide to ignore me, but just as I was getting to the front of the line and a male guard asked me to pull down my pants (revealing just the hair on my stomach and the beginning of the trail below that), the female guard finally came over and leaned in close to my lips. I think she had seen how panicked the look on my face was as I reluctantly started to pull my pants down.

At this point the dream became more like a scene in a film, where I was observing from a different perspective than that of myself in line. Now I was one character among a cast of many. What I saw was a small dude (me) talking to a guard, but at the same time I could also see people in both the men’s and women’s lines noticing that I was talking to this female guard, perhaps trying to curry special treatment. It was like I could understand it from their perspectives, too. I don’t know precisely what was said to the guard because of that perspective—even though I was the one saying it. I did have a general sense of what was conveyed to the guard, which was that I couldn’t pull my pants all the way down for the strip-search, because then both the other men and some women would see me and know that I was different. That if that happened, I would of course be beaten and raped when we got into the general population on the other side of the male and female admitting areas.

The guard immediately understood. Not in a nurturing, kind way, but rather in a way that suggested she and the other guards must’ve had a memo or perhaps a sensitivity-training session about “these kind of people whom you might see in the prison population,” and she was just following protocol to keep me out of danger. Doing her job.

So while a few of the other prisoners looked on, again, from both lines, I was back in myself (not the actor in the scene I was watching), and the guard led me into a separate chamber to take off all my clothes and put on an orange prison uniform while she and a few other male guards looked the other way. I was given my requisite supplies and the number of my cell. And then

I was released back into the general population, among other men and women carrying their blankets and towels and soap toward their quarters. I walked by rows and rows of open cells, which were divided by gender, two or four people per cell. There was the stainless-steel toilet in the middle of each room, completely on view for all to see. I was immediately terrified by the prospect of having to sit down to pee in front of everybody, but then I remembered that the female guard had acted like everything was OK, so I told myself that it would indeed be OK, just keep walking and try to find the right cell. Two women inmates in orange jumpsuits approached me then, as I neared the common part of the prison (gym equipment, ping-pong table, TV). They spoke to me sympathetically, like they knew my “secret” and would help me keep it from the men in the joint.

One of the women looked at my papers and pointed to a small cage that was more like a compartment that you see in Japanese airports or business-commuter hotels. I had to climb the wall to enter the tiny space, but it would be all my own, no cell-mates. Just a bedroll and a small, adjacent cement surface to put things on. A notebook and pen and an alarm clock were all I really had, besides linens. As I was slowly setting these few things up in my space, the sympathetic women whispered something about how another person with “concerns like mine” had been there just the month before—and she pointed out the private, small bathroom that he’d had access to for showering and toilets. I remember feeling immense relief at this idea, but then also equal amounts of fear that guys would see me going in and out of the bathroom enough times that one or two of them would eventually figure it out, and the information about something being different about me would spread from there.

I asked one of the girls how we were supposed to know how long we were to be confined, but they said it varied. At dinner and during the free time before bed, everything seemed normal. When it was lights-out and the barred door slammed me shut in my pod, I remember feeling completely safe, but as I lay there listening to the night sounds of the prison with the ceiling alarmingly close to my nose, I was thinking to myself over and over, That door is going to fly open first thing in the morning. Thinking, I’m going to have to act tough and like nothing’s out of the ordinary. Fake irritable bowel syndrome, or colitis. I was thinking, At least I have as many tattoos as a lot of these guys, even if I can’t bench a lot, and I lay there sleeplessly trying to do the complicated algebra in my head: how many guys would see me use the bathroom and showers how many times per day, how exponentially fast that information would travel, and then how many days that would buy me before the worst would happen. Which I knew would happen; it was only a matter of how long I could last.

VIII. The Little Surfer Girl

I was recently interviewed in person by a reporter for LA Weekly, the main alternative paper in my native Los Angeles. The story was to appear in the front of the book column, just six or seven hundred words (of the style, if not the quality, of the New Yorker’s “The Talk of the Town” department). My book9 at that time had just appeared on the Los Angeles Times best-seller list for a couple of weeks, and

I had been in town for events at local bookstores a few weeks prior to that.

When the reporter showed up at my folks’ house (where I was staying), she seemed nice enough. It was my last day in town, and the last thing

I felt like doing was sitting down for an interview. But I did, for three hours. I don’t need to go into all of the details, but suffice it to say that I made a connection with the reporter, that she seemed sympathetic and easygoing, and she laughed at my jokes pretty consistently throughout the interview. She also seemed to enjoy herself, as was confirmed by a follow-up email she sent me: “It was great talking with you. A lot of people I interview get caught up in their own hype. But you say what’s on your mind. It’s refreshing.”

About a quarter of the way through the interview, the reporter mentioned that she was surprised to learn from my publisher’s publicist that I had not been born male. She then asked me, “When did you have the surgery?” at which point I calmly, nondefensively launched into the requisite spiel about how there is no “one surgery”: you don’t show up for an appointment at the hospital one day, and then leave the next morning as another gender. She seemed to get it. Yes, I explained frankly, this was a fact about me that I am not secretive about, but at the same time, it wasn’t what my book was about, and I thus wasn’t going to be comfortable if it was to be the main focus of our interview and the story. I brought up, by way of example, a few other publications (even a gay one) that had mentioned that I was transgender merely one time, and then proceeded with their review or interview. Again, the reporter seemed to feel me when I explained this, in no uncertain terms stating that all the trans-related stuff we were discussing was not intended for her story. Perhaps things would’ve been different had it been an in-depth profile, where there’s a lot more time and space to at least attempt to approximate a life; but in the space of six hundred words, I believe it is virtually impossible to convey the nuances and complexities of gender identity in any adequate way. And even more so if you don’t bring a tape recorder to the interview. Which she did not.

When the piece appeared, I was not super-psyched to see that it began: “So, there’s this man who used to be a woman, who wrote a novel about a polar bear who moves to Hollywood and becomes best friends with Leonardo DiCaprio.” Not great, but if that was to be the reference to my gender identity, then so be it. I kept reading. To spare you the torment of a 50 percent inaccurate and 95 percent snarky fluff piece, I’ll just say: in the space of six hundred and fifty words, this reporter managed to mention my gender identity nine (9) more times.

The most egregious of these: when she described me as having been “a little surfer girl” in my youth. I know this probably doesn’t sound like much, but I would never in my life use that term to describe myself. When asked if I surfed and did other ocean-related things when I was a kid, I did indeed answer in the affirmative, but I never used the word girl throughout the course of the interview—not when talking about surfing, not when talking about my youth, never. I don’t even say it in real life, outside of a formal interview context. Because it’s simply not accurate, doesn’t begin to tell the whole story. And it’s not a term that feels particularly good, either, like any time I hear the words she or her in reference to myself. It’s all more complicated than that, and I took a lot of time explaining this to the lady, because it seemed like the right thing to do if she was going to be asking about it.

To call me “a little surfer girl” was like, I don’t know. I just don’t think you do an interview with a now-skinny person and constantly bring up how they were fat in their youth, and how everything they do now must relate to that transformation. You don’t keep banging that same “fat” note over and over. Especially when asked not to. You also wouldn’t mention ten times in six hundred words if I were physically challenged in some visible way, or had epilepsy. You wouldn’t go ten rounds about my race if it were a difficult or fraught aspect of my past; you wouldn’t even do it with a gay person anymore—the one punch line over and over to make sure everybody knows: freak! In addition to my gender status, I also happen to be Jewish—and I didn’t see the reporter referencing my being Jewish ten times, either.

I am certainly not the first person “of difference” who does not want to be known only for that difference. I am reminded of a time in early 2007 when I did a reading in Los Angeles with the author and poet Chris Abani.10 We went to coffee after the event, and this subject came up. Chris remembered reading that review of my (then) new novel in the New York Times Book Review, wherein the reviewer took time out to tell the reader that I, the author of the book in question, was female. Chris recalled thinking that was odd when he originally came across the review. He told me he was likewise getting tired of reviewers or interviewers insisting upon “reviewing my body” instead of the work. In fact, he was surprised when his physical body wasn’t the subject of reviews and interviews concerning his body of work.

At a certain point I’m just a man who writes books, advocates for pit bulls, likes both early-twentieth-century jazz and hip-hop as well as old airplanes, has a lovely wife and two kids—and not a transman who is all these things. Transgender is a term that implies an identity forever in transition. But I cannot think of a living person who is not in transition to some extent, regardless of gender. That’s what we do as humans: we evolve, constantly.

Dr. Marci Bowers, the rock star of the transgender-surgery world who you see on all the TV shows about the subject, seemed to suggest as much to me when I spent a few days in Trinidad, Colorado, interviewing her for a profile I was writing about her. I didn’t completely understand it at the time, a couple years ago, but I think I’m starting to now. She insisted she was just a woman. Not a trans woman any longer. Not even really transgender. It’s just one aspect of your history, being trans, like you were born in California, were orphaned at age eight, or you were adopted, had some all-consuming illness, went to Harvard, went vegan, lived abroad, accidentally killed a girl with your father’s Oldsmobile. Just one of the many things on the way to becoming the person you are today, man or woman—or anywhere in between. Because every day is filled with transitions, from the tiniest and most insignificant, to the largest thing you can possibly imagine (and, for some people, going from one gender to another is The Biggie).

I don’t want to perpetuate any secrets, and I don’t want to straight lie to anybody, but I sometimes wonder if and when I’ll ever just be a man in this world.

IX. A Few Words About Pronouns

What’s the first thing people ask when a woman is going to have a baby?

Is it a boy or a girl?11

Sure, the halfhearted “Is it healthy?” question is usually soon to follow for good measure and/or manners, but mostly folks want to know what the sex of the baby is. Or they don’t want to know what the sex of the baby is. All about the sex: We told the doctor not to tell us! We wanted to be surprised! Well, I’m here to tell you that gender surprises can happen anytime. Just ask my parents.

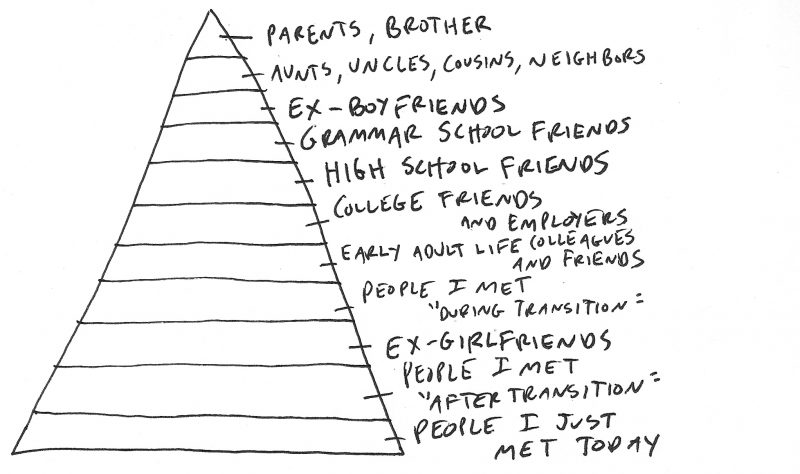

A few years back, if I had drawn a pyramid to represent who has it “hardest” with respect to the subject of me and pronouns (with “most difficult” on top, and “not really difficult at all” on the bottom), it would look have looked something like this:

Notice that I am nowhere on the pyramid. This is because for many years I was generally apologetic about my situation. I didn’t want to make anybody feel uncomfortable, ever, so I readily shelved my own discomfort with being referred to by the wrong pronoun. In my early twenties, I had been in a boy-band called the Backdoor Boys, so being a guy was all just in the name of satirical performance! And for years after that, I minced around my preference about gender pronouns in real life, splitting the difference, perhaps to make it less jarring for people, asking for no gender pronoun to be used in reference to myself. But that got tricky: “T said T wanted to stop at T’s house before we go to bingo.”

Closer friends naturally transitioned into calling me he, which felt best, but when other people messed it up, I was always like, “Whatever! You can even call me ‘asshole’ if you’d like—I’m sure it’s gotta be really hard for you!” As for my parents, I remember saying to them one time early on, “You don’t have to call me he if you can’t bring yourself to, but please try not to use she.”

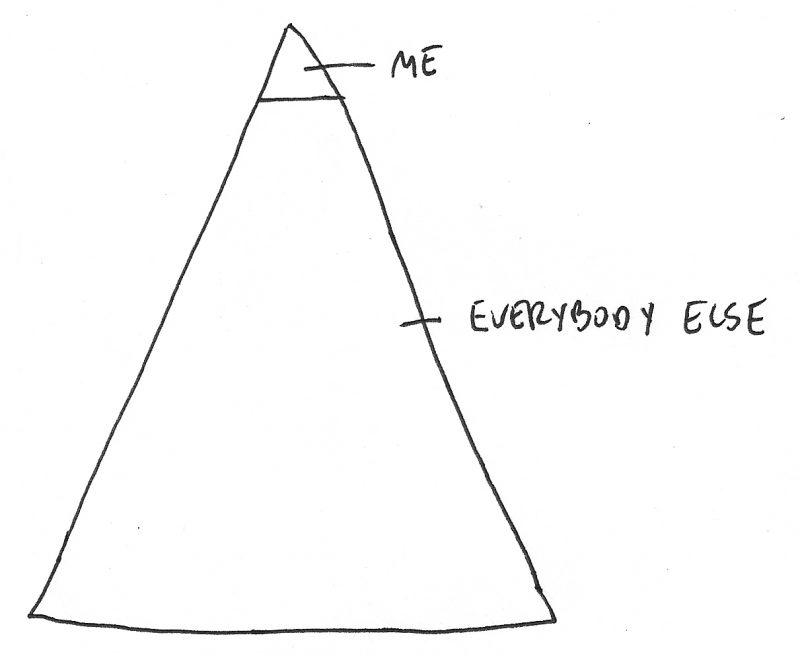

But now I wish I hadn’t said any of that. And if I were to draw that pyramid now, this is what it would look like (most days):

Once I switched over to he, and let people in my life know about it (of course in a self-mocking way that let everybody off the hook except myself), that’s when I got off the apologetic train. After scores of “It’s so hard, because I’ve always known you as she,” and “I know it’s no big deal for you, but it’s really hard for me,” I stopped being so goddam accommodating, and started gently correcting people, even if it made them mildly uncomfortable in the moment. Because you know what’s mildly uncomfortable? Not being seen for who you are, especially by people who are supposed to know and love you. You know what else? People insisting you are something you are not, and likely never have been. Meeting somebody who has been explicitly told you are male, and then hearing him or her refer to you as she within five minutes of the introduction.

I’m sorry, but I don’t understand what’s so fucking hard about calling me what I am, what I prefer. If you are introduced to somebody as John, it’s not cool to decide to call him Sally, or even David instead. Or, say you have a good friend you’ve known for years. You used to go out to bars with this guy, snort drugs, hook up with strippers, and then wake up and do it all over again the next night. If this guy is now five years sober and happily married with 2.5 perfect children, you probably wouldn’t call him up every day and ask him to score some coke and go whoring with you. (Especially not if his wife answers the phone.) It’s not the world he lives in, even if you think or wish he still did. Maybe it never was him, it never quite fit, and he had to go through all that to get to the happy-rainbow place he is today.

Or say you always played basketball with a buddy; that’s all you guys did together—played on your high-school team, at the Y, down on the corner, at Chelsea Piers, in one of those oppressive adult leagues where everybody has to buy the uniform and celebrate at the sponsoring Irish pub after all the games. But then your buddy is in a gruesome Staten Island Ferry accident, leaving him paralyzed from the waist down, exiled permanently to a wheelchair. Would you forevermore go up to him, see him sitting in that wheelchair, and then be like, “Yo, you wanna go down to the corner and play some pickup? Oops! I didn’t mean to say that! Sorry, it’s just so hard to get used to!”

No, it’s fucking not. You know who it’s hard for? The dude who never gets to walk again, never gets to play pickup hoops with his buddies again, never gets to use his dick again for anything outside of involuntarily urinating into a bag. That’s who it’s hard for.

All these not-quite-right analogies are just an incredibly grating way to say that it always makes me feel like shit inside when people refer to me as she. It doesn’t matter if it’s with the best of intentions, or whether it’s obvious to those in earshot that I am male, and nothing’s technically been lost, that there’s clearly been a mistake. Or even if they are talking about the past. So as usual, I’ll leave it to my unbelievably intuitive and intelligent wife to say it better (and more generously) than I ever could, better than I’ve personally ever heard anybody—trans or not—put it:

I think about this sometimes. How I would feel if I were called sir while I was on a date, wearing a dress and heels and cherry lipstick. How abnegating it would be to have the world look at you and decide, no matter how many signals you give, that you are something you are not. There is this misbegotten notion that trans men and -women are about playing dress-up and fooling people. But to be trans is to feel the truth so acutely you can’t fake it. It is to be so consumed with the truth of who you are that you are willing to risk everything to inhabit it. To refuse to be what other people have decided you are—this is an act of courage few individuals dare try. I know I didn’t.12

X. Some Things People Assume I Must Understand about Women but Actually Don’t13

(1)The physical pain involved in menstruation

(2) The emotional pain involved in menstruation

(3) How to comment properly on an outfit, hair, shoes, makeup, dress, etc.

(4) How much sex is enough

(5) How completely natural it is to feel one way but then also feel the complete opposite way simultaneously

(6) How it feels to be dismissed

(7) How stubble feels against softer skin

(8) What people think of you if you dare to argue for what you believe in

(9) How certain tasks, by default (or perhaps through the fault of history), tend to fall on women

(10) The tyranny of hormones

XI. A Brief Interview with my Wife14

TC: When you first saw that photo of me—before we ever met or you knew who I was, or I knew who you were—what did you think of me? When I tell the story, I always say you just thought I was “some writer guy.” Is this close to accurate?

AGC: It is and it isn’t. I did think you were a guy. But there was always something else there. Something that made you magnetic in a way I’d never felt before. I don’t think this has to do with your being trans (more to do with falling in love), but I suppose, now that you are asking me to consider it, it could, if only in that something about you radiated infinite possibility.

TC: Do you think everybody who came to our wedding “knew” about me?

AGC: Yes. First, because they were our closest, dearest friends. Second, because information like this travels. It is such a core issue, and it brings up so much inside folks, that I can’t imagine it being tamped down. Lastly, it was likely a great comfort to our parents to have a chance to talk about all this complicated (for them) stuff in a safe, understanding place, during one of the most traditional rituals on offer.

TC: Do you believe there’s something different about my biology? Like, do you think I may not have the typical XX chromosome setup that those designated as females at birth have?

AGC: That is a good question. I know you are resistant to the biology is destiny argument. As am I. But that is probably just stubbornness and ego. Fuck you, genes!

I don’t care what you say I’m meant to be: an addict, a depressive, slope-chinned, acne-prone, a cheat, a girl. Then you read the medical journals.

TC: How many minutes do I have to be in a public men’s restroom before you start picturing me being raped and killed?

AGC: On average, three. Five if I can see the line. Two if we are at a dodgy truck stop.

TC: How many times a day do you worry about something violent happening to me? Is this number compounded by my being trans, or would you worry anyway?

AGC: I worry with every breath. The only time I am not worrying is when my brain is being distracted by other, lesser attentions, like reality TV or my work or what to make for dinner. But the hum of fear is always there, as it is for the children. Sometimes it is manageable. And other times, say, after reading the newspaper, or another study about girls and rape, or watching something hateful happen on the street, it washes over me how thin the line is between our happy, sweet lives and the moment that could end all of it forever. Because of my experiences and natural inclinations, it isn’t challenging for me to imagine the worst. Sure, I would do this no matter what, but the undeniable fact that trans men and women are statistically more likely to suffer myriad abuses doesn’t exactly help. Just as having been the victim of violent crime myself doesn’t make me inclined to be comfortable releasing my girls into the world. And yet, what choice is there? So we truck along, hoping, praying, studying the truth from the corner of our eyes. There aren’t enough fingers to cross.

TC: List five ways that I am “typically male.” It’s OK to use stereotypes and add a sixth if five seems inadequate.

AGC: (1) You are self-involved.

(2) You watch TV with your hand down your pants.

(3) You never worry about how much you’re eating.

(4) You get territorial and jealous.

(5) You don’t apologize for yourself.

Bonus: You spit on the sidewalk.

TC: Are you secretly waiting for a man who’s taller, bigger, smarter, richer, tougher, more handsome, more talented, and—most important—was born male, to come along so you can leave me and run off with him?

AGC: No.

TC: Do you think your mother thinks I’m good for you?

AGC: Yes.

TC: What if one of our kids turned out to be transgender? (For the record, I don’t want that to happen.)

AGC: I’ll blame you.

TC: How happy are you that this is the last question?

AGC: As if.

XII. But What about the Children?

I’ve been thinking I should probably include something about the children here, perhaps something funny, like when I had to, for the first time, explain the definitions and purposes of periods, cramps, uteruses, and vaginas to the girls while the three of us were on an emergency mercy-mission to the pharmacy to buy tampons for their mother one rainy night.15 Or something heartbreakingly sweet, like how soon after I started living with them and my voice wasn’t as low as it is now, the older one expressed to me that she wasn’t uncomfortable with my being “a different kind of boy,” but that her sole concern about it was that she worried that it made me sad if a waitperson mistakenly called me she when we were out to dinner.16 Or perhaps I could include some sort of sociological observation, like how I noticed early on that being with the kids made me pass more readily than anything else when out in the world: for example, in the bubble of Disney World, where nobody would ever question that I—even with a voice that didn’t entirely match my body—was anything but a real, normal, standard-issue dad, standing in the blazing sun with his wife and kids on line for Big Thunder Mountain Railroad.

But you know what? I’m feeling particularly protective of the children right now, and likely always will, so that’s all I’m going to say about them right now.

XIII. Another Excerpt from a Draft of the Letter I Eventually Sent My Parents

I don’t really know how to continue to “protect” you from this information, which is not new and has been out there for a long time. But I can say that some of your past reactions to the details of my life have colored my willingness to continue to share those details with you. I take responsibility for my side of that; it has been a default choice on and off to include only information that I know will go over without an emotional explosion—it’s exhausting for me to constantly be teetering on the edge of disappointment. I’m sure the denial is equally exhausting to you. As a result, it’s frequently been easier not to reveal all things to you. In the past, the negative reactions involved (often to any change, big or small) have included fear, skepticism, and anxiety—in lieu of things like acceptance, or a willingness to try to understand, or to be happy because I am happy and able to be myself in the world. Life is short, and who knows how much of it is left at any given time. You raised me to be strong and smart enough to know and be myself. Not to live a half life.

XIV. Six Fears (in no particular order)

(1) That I might be trading in a couple years at the end of my life so that I can live in a body more aligned with who I am now, while I am relatively young and healthy.

(2) That my kids will hate me when they “find out” that I’ve been lying to them about who

I am, even if I haven’t been lying—the way my brother was angry with my parents when he “found out” he was adopted, even though they’d been telling him as much since he could speak.

(3) That my wife will leave me and I will end up a sad, lonely tranny freak with nobody to truly understand and love me in my dying days.

(4) That, like Sarah Kurtin in high school, whose only wish was not to be remembered for her perfect score on the SAT (and yet that is all I seem to remember about her), I will always be known primarily for the thing I’d like not to be known for.

(5) That I’ll end up in the ER after some grave motorcycle accident, and I will be unable to speak or advocate for myself and my physical situation while heroic efforts are being made to resuscitate me, and my clothing will be haphazardly cut off my body with the help of those EMT scissors that can cut through virtually anything, even a penny.

(6) That just as quickly as I think I’ve managed to capture something here, it will be gone. For one, because I could wake up tomorrow and my feelings about all this (not my gender identity, just the business surrounding it) could change. And, second, that even if I’ve managed to capture anything here, I’ve squandered my one opportunity to do so, because I will have done a mediocre job of it. The impudence of trying to encapsulate a life at all, whether in the space of six hundred words—or sixty thousand.

1. See section VIII of this essay, for example.

2. See: all of history.

3. Actually, not whatever. That was fucked up, and it has eaten at me for years. I have considered writing the Times to ask for a correction, but what’s the use? How would I explain to them that in their reviews of “normal” people, reviewers don’t take the time out to straighten out readers’ assumptions about an author’s identity: “By the way, Jonathan Franzen is a straight, white male.” There was no gender pronoun on my book at the time; there was certainly no female gender pronoun on any of my own press materials or website. It was a violation for the reviewer to state unequivocally in a paper of record that I am female. It was simply not true. Not then, nor ever, really. It’s just never been as simple as that. I keep hoping one day I’ll stop caring, but short of a complete correction in that goddamn review that will likely be around for the rest of time (plus a gilded letter of apology and fruit basket from the reviewer), I don’t know if that particular parenthetical will ever stop bunching my boxers.

4. This may seem far-fetched, but just ask my wife: she’ll gladly confirm it happens all the time when we are out in public, or meet new people (and she is no shrinking violet).

5. While I know these three things in theory, that doesn’t mean I am very good at them or necessarily remember them all of the time in practice.

6. Written a few months after meeting my wife.

7. Which lists me as male (both in real life and in the dream).

8. Ibid.

9. A graphic novel called The Beaufort Diaries, about a polar bear who attempts to escape extinction by going Hollywood. There is nothing in the book explicitly transgender at all.

10. Who is black and was born in Nigeria. A fact I never would’ve mentioned here if it weren’t actually relevant to the story. Now I’m going to attempt to resist mentioning it nine more times in the space of this short paragraph.

11. Coincidentally, a question I used to hear, often out of the mouths of children, and often in public women’s restrooms, but always in reference to me. This was years ago, though, when

I didn’t pass as obviously as male and thus was using about 70 percent men’s and 30 percent women’s restrooms, depending on the seeming safety of the situation—and when I probably didn’t know what the fuck I was either.

12. This is a tiny excerpt from a much-larger essay my wife was asked to write for O, The Oprah Magazine, about falling in love with a trans man. I was not identified by name in the piece, though there were a couple photos of us accompanying the essay (of course my hair looked bad because the stylist insisted on pouffing it).

13. As my wife has said to me, in the heat of some stupid argument in which I was likely being a dick: “It’s astonishing how little you know about women.”

14. Containing far fewer questions than I probably should ask her; there are a lot of questions I’m just not sure I want the answers to. Starting with: “Do you sometimes wish I were a ‘real’ man?”

15. “It’s not fair you’re a boy and don’t have to bleed,” observed the little one, age seven at the time.

16. To which I responded by explaining that it didn’t make me sad at all, that it was completely normal for those mistakes to occur, and that there was nothing for her to worry or concern herself about. So basically all lies, except the last bit.