When I was still a fresh-faced young tot, I became obsessed with this curious little book called Maze, by Christopher Manson. You also might be familiar with it. Maybe you, too, spent countless hours hiding in the chicken coop with this handful of bound pages, a mere forty-five of them in all. It was not by choice, this obsession—I would have much preferred to be playing Ghostbusters on my friend’s Commodore 64 or watching Three’s Company or Dirty Dancing on our shitbox Panasonic television so as to absorb a pathological sexual tension that I craved yet still didn’t understand. But both of these activities were lightly forbidden, or perhaps heavily curtailed would be a better adjective to describe my parents’ well-intentioned, pseudo-relaxed, post-hippiedom style of child rearing, and so I was left with my crappy wooden toys and my books, and, in particular, Manson’s beguiling Maze.

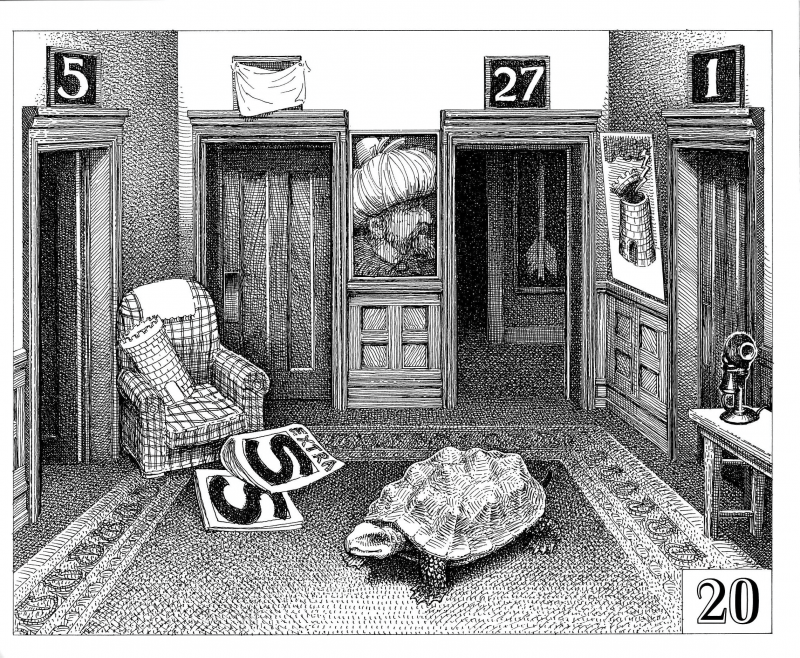

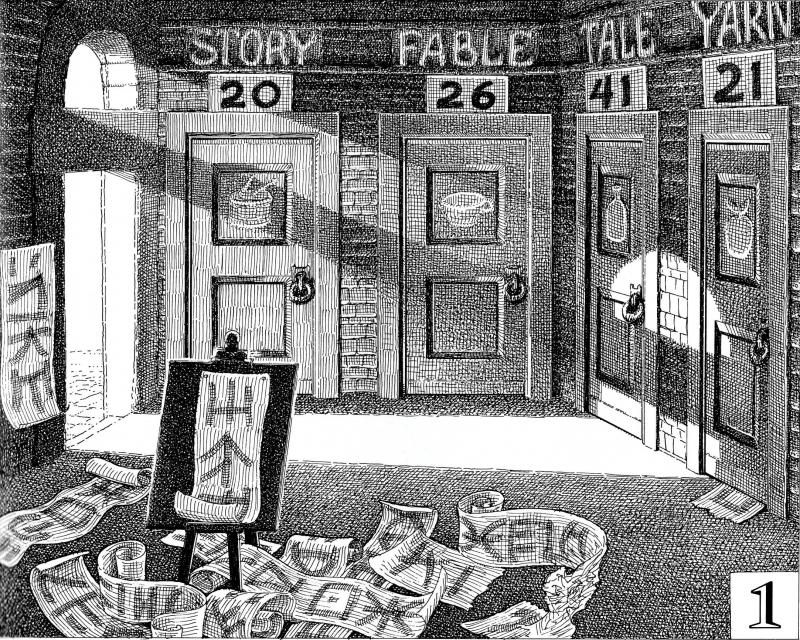

On the first page of Maze, the reader is invited into an old, sinister labyrinth by a mysterious host who speaks in riddles and looped syntax: “Like all the others they think the Maze was made for them; actually, it is the other way around,” our guide declares at the maze’s entrance. Each page of the book depicts a different room of the maze in an intricate black and white woodcut, and each room has a series of numbered doors that lead to other rooms. When you choose door 20, for instance, you turn to page 20, where a new room with new doors awaits you. Such a simple, beautiful idea for a book. The rooms are laden with peculiar, often-creepy clues that haunted my dreams—torn fedoras, handless statues, an abandoned cane, stuffed birds. When pieced together, the clues are supposed to lead you eventually to the glorious center of the maze, on page 45.

I never arrived at page 45. Legitimately, that is. I was never even sure you could actually do it, but I remember the naughty feeling of turning to page 45, breaking the thread of my path as if boring a hole through the creaky walls of the labyrinth, and wondering how I could ever get there without cheating. What was amazing about this book was the powerful, unbreakable illusion it cast on my tender mind. Something about its perfect containment in a slim little book and its potent suggestion of this vast, three-dimensional labyrinth of silent nightmares caused me to return to its serpentine pages again and again, and, in the end, with much more frequency than to any quick-fix video game or illicit Patrick Swayze photoplay masterpiece.

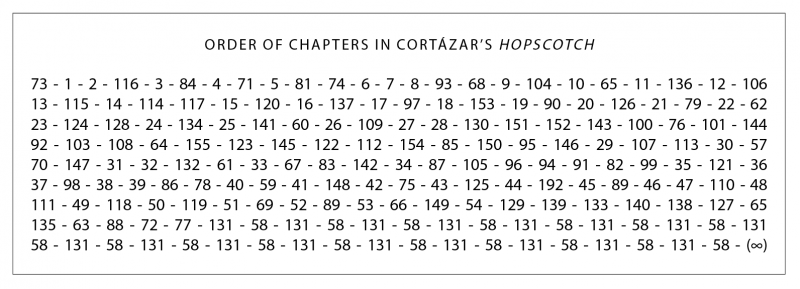

Julio Cortázar casts a similar spell in his contranovela Rayuela (or Hopscotch), a wandering meditation on Paris, Buenos Aires, jazz, unrequited love, and yerba mate-drinking, in which you as a reader are faced with a choice: read the book straight through “with a clean conscience,” ignoring the last ninety-nine “expendable chapters,” or follow the directions at the end of each chapter (chapter 2 leads to chapter 116, which leads to 3 and then to 84, and so on), bouncing around the book seemingly at random, until you are finally caught in an infinite loop between chapters 58 and 131. One can argue about the success of the venture, but I happen to find it heartbreaking and moving in its convolution, in its suggestion that any and all stories are possible, and, in the end, no matter who the storyteller is (writer, reader, or both), all narratives fail to capture our ethereal, drifting experience on this planet. Cortázar manages to pull off these maneuvers because he never loses sight of his characters: our antihero, Horacio, and his supporting cast of lonely urban misfits are perfectly embraced by the haphazard form and nonlinear delivery of the book itself. Then again, maybe my weakness for the Hopscotch experiment was due simply to a lingering nostalgia for my beloved maze, and I knew Cortázar was trapped in the same dilemma of pining for his own ever-elusive page 45.

I find myself again recalling the tender allure of page 45 as we stand on the precipice of reinventing the book. This sounds dramatic, and perhaps it is, for I have no doubt the book in its current printed form will endure probably as long as we manage to keep ourselves alive on this planet. There have been many announcements about the death of the printed word, about the death of the publishing industry, about the death of the novel, about the death of good literature. This is what we do whenever we sense a change in the sea. It happened with the invention of the printing press, and the blasphemous migration of books out of the hands of the priests and into the homes of common folk; it happened with the invention of the telegraph and the perceived bastardizing of the language through abbreviation and code; it happened with the invention of the telephone and the perceived collapse of social propriety and the death of letter-writing; it happened with the invention of radio and the perceived horror of a culture falling victim to lazy mispronunciation, immigrant accents, and the overall collapse of the English language; it happened with television and the perceived deaths of radio and the imagination; it happened with the ubiquitous growth of the Internet and the mass proliferation of cell phones and iPods and robotic dogs (actually, I am still terrified of robotic dogs). So fear and technology are well-acquainted bedfellows—in fact, if a new technology does not send people into a tailspin of doomsday scenarios, then chances are this technology is not going to have any sort of pervasive cultural impact (sorry, Segway).

And yet, somehow the rise of e-books feels different from the quaint technologies I have listed above. This time, it’s personal. I say this first and foremost because I am a writer and this is my domain, and so it is my turn to push the panic button and rue the loss of this brilliant technology. And, yes, let us be perfectly clear: the printed book is a brilliant technology. An old technology, a relatively simple technology, but a technology that has stood the test of time. Let us do our duty and sing the praises of books.

(1) Books are portable—they fit nicely into most modern handbags; we can stack at least twenty of them on our bedside table before it becomes dangerous; they can easily be loaned to friends; they can be infinitely rewound without the aid of machines; you can even continue to read them during take-off and landing.

(2) Books are palpable—their golden-ratio dimensions feel right in the lap and the hand; they smell scrumptious and unsolved when you first buy them; you can scribble notes in their margins; the turning of their pages is a metronome for the arc of our narrative processing; they get marked with the fingerprints and coffee stains of our love and neglect; you can even burn them for warmth.

(3) Books are vessels of the imagination—they are inherently limited by their boundedness, and it is this very boundedness that gives them their great power; they allow our imagination to erect the intricate walls of the maze beyond the beautiful white margins of the page. By not showing us everything (as those uppity photoplays do), by denying us through their inherently limited evocation, books ask us to do the heavy narrative lifting, and this is why literature will always outstrip other storytelling-delivery systems in terms of imaginative lasting power and the intimate, voluntary story-world participation by the reader.

For the bibliophile in all of us, this list makes us feel warm and fuzzy inside—ah, nothing like a good book in the lap, finger and thumb poised, waiting for your eyes to catch up so that they can flip the page—but in fifty years, this list will most likely seem ridiculous, like a Victorian-era man arguing the benefits of candlelight over Edison’s newfangled electric lanterns. When I conjure how people will take their literature in the future, I see humans clutching their beloved screens or wearing their beloved Immerso-Goggles™, making gestures at a glowing, multimedia splash page that looks not unlike the three-dimensional sexed-up opening menu of a DVD.

“The reader” gestures to cue the ka-bling of the book trailer (which is now the new book cover), before moving cautiously into “chapter 1,” which, unfortunately, still demands actual reading, though it is now heavily supplemented by an (optional) roving narration by “the author,” pictures and music videos of the actual neighborhood the book takes place in, several risqué deleted scenes, options to improve the story on your own, and a side-panel of real-time Twitter reviews. At the end of “chapter 1,” the reader makes a split-second thumbs-up/thumbs-down decision to download the rest of the book or move on to the next expendable media morsel. Given this (admittedly somewhat dramatized) vision, I am both appalled and excited—for from a storyteller’s point of view, the opportunities to engage a reader in new story-worlds seem simultaneously limitless and horrific.

Indeed, the voice of the storyteller appears to be the missing one in this cacophony of press around the latest e-book–reader release. The media are obsessed with examining the economics of e-books (will the Jurassic publishing industry survive?), the technology (e-ink v. LCD?), the corporate controversies (Apple v. Amazon v. Google!), the delicious apocalypse of the moment. But what about the actual delivery of the story? The intoxication of narrative; the unsettling shiver of formal ingenuity; the silent beauty of sculptured, deeply flawed characters; those Dada-esque metaphors that are so wrong and yet so right; those juicy, perfectly nonsensical slices of dialogue (I can hear it! I can hear it!)—in short, what about this slow-burn addiction so many of us suffer for the unending power of words? What challenges do we writers face when writing for the blinking, beeping, infinitely reframeable screen instead of for the static, four-cornered, flammable page? Will we have to bend and shape our craft to the new devices, or will the new devices bend and shape to us?

One starting point seems to be the persistence of the page as a delivery device. “The page” has been around in one form or another for thousands of years, and while there are some theories that the page’s particular rectangular shape and orientation found their roots in the natural layout of sheepskin parchment (how wonderful: books are books because of the shape of sheep), I find it more plausible that the page’s form came about the way most brilliant things come about: through slow trial and error and gradual improvement until the efficiency, design, and cost of a technology achieve optimal stool-like triangulation. And in Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg, the perfecter of movable type, we were lucky to have not just a visionary inventor but a master designer, in that he imposed a strict ratio onto his page’s dimensions: the golden 5:8, which happens to nestle nicely into hand and elbow and the very skeleton of our humanness. In fact, a study by designer Jan Tschichold found that many medieval manuscripts conformed to a series of intricate ratios that he identified as “the Van de Graaf canon.” Every aspect of the page was highly purposeful, particularly the ample size of the margins, which allowed for “illuminated” illustrations to augment the manuscript, or beautiful, intricate “glosses” or commentaries to literally enfold and surround the main column of text. Tschichold, bemoaning the lost elegance of these designs, writes: “Though largely forgotten today, methods and rules upon which it is impossible to improve have been developed over centuries. To produce perfect books, these rules have to be brought back to life and applied.”

When I look at these old illuminated manuscripts, I wonder at their simultaneous utility and elegance. Confronted with such considered balance, we readers secretly sigh with relief. As is the case with all of the best design, the form of the book fades into the background, allowing the content to shine through, and yet a part of us is still deeply aware that we are experiencing an object of great mindfulness, that this story will be delivered to us in the proper way, and we feel that imperceptible hum of form and content uniting in concert.

As I write this, e-books have not been able to achieve the same sangfroid delivery hum of the book. Perhaps it is no surprise then that e-readers are currently obsessed with mimicking the printed page as best they can. The animation present on the iPad, on which you literally can watch the page turn with your fingertip, was cited as “comforting” and “satisfying” and “just like reading a book in real life” by early reviewers. Of course, this is nothing like reading a “real book”—whatever that means. Nor should it be. This kind of thinking is a lingering form of the “horseless carriage syndrome,” in which we are trying to reconstruct old technologies in a medium that does not do old technology well. The screen cannot be fondled or written on, folded or torn. The screen does not smell (not yet, at least). We should not simply re-create the sparse beauty of the printed page on the screen. We can learn from the page’s minimalism, from the power of its margins, but if we are to be true storytellers in this new medium, then we must embrace the power of the medium and move into new standards of delivery that use the page only as an instructive starting point.

Writer/designer Craig Mod, one of our most thoughtful voices investigating the future of the book, echoes my wariness of attempting to just imitate the printed book on the screen. He writes: “The canvas of the iPad must be considered in a way that acknowledges the physical boundaries of the device, while also embracing the effective limitlessness of space just beyond those edges.” Mod suggests, “One simplistic reimagining of book layout would be to place chapters on the horizontal plane with content on a fluid vertical plane.”

Again, when I hear this, the simultaneous excitement/horror bells go off. Content on a fluid vertical plane? But what about the tangible boundaries of my beloved page spread? What about the narrative beat of the page flip? Limitlessness of space ≠ powerful story space.*

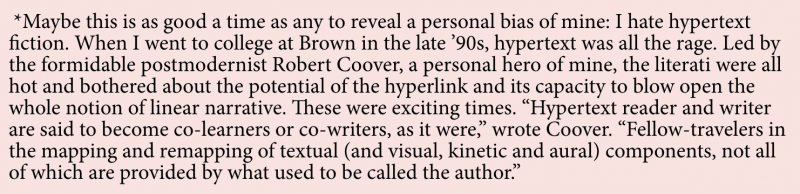

What used to be called the author? Excuse me? Although I can’t help but be a little offended by the elimination of my job, I also can’t help but be swept up in the excitement of Coover’s declaration: it all sounds so amazing and subversive and incredibly geeky. But as I walked into my first hypertext “show” at Brown, in which students were demonstrating their hyperspace stories (several of which were just borderline cybersex Choose Your Own Adventure pieces repackaged as groundbreaking postmodern electronic literature), as a “reader” of these stories, I came up against the obstacles that have, at best, prevented hypertext fiction from blossoming beyond the geekworld, and, at worst, sunk the ship before it ever set sail. That is, hypertext fiction, with very few exceptions, was mostly bells and whistles, fireworks and birdcalls, virtual heavy petting and mouse clicks. These stories lacked the sense of urgency, the deep conscript of heart that traditional print narrative cultivated. Yes, there was co-learning going on; yes, the reader had become a navigator of sorts; but unlike Cortázar’s Hopscotch, in which the inherently limited interactivity was actually raising the emotional stakes of the story, the form of these hypertext stories was dominating the content of the narrative. You were becoming a curious tapper of mouse buttons instead of an immersed, obsessive reader. If you click on this link… it shows you a naked woman. If you click on this link… it shows you a naked woman with the head of a walrus. Interesting, but like most art that is produced in the world, these hypertext creations seemed to be much more engaging to create than to consume. So I left that wildly hip hypertext show at Brown and swore off the technology. If I am going to be a writer, I thought, then I can’t get distracted by the bells and whistles. I need to learn the craft at its most bare-bones.

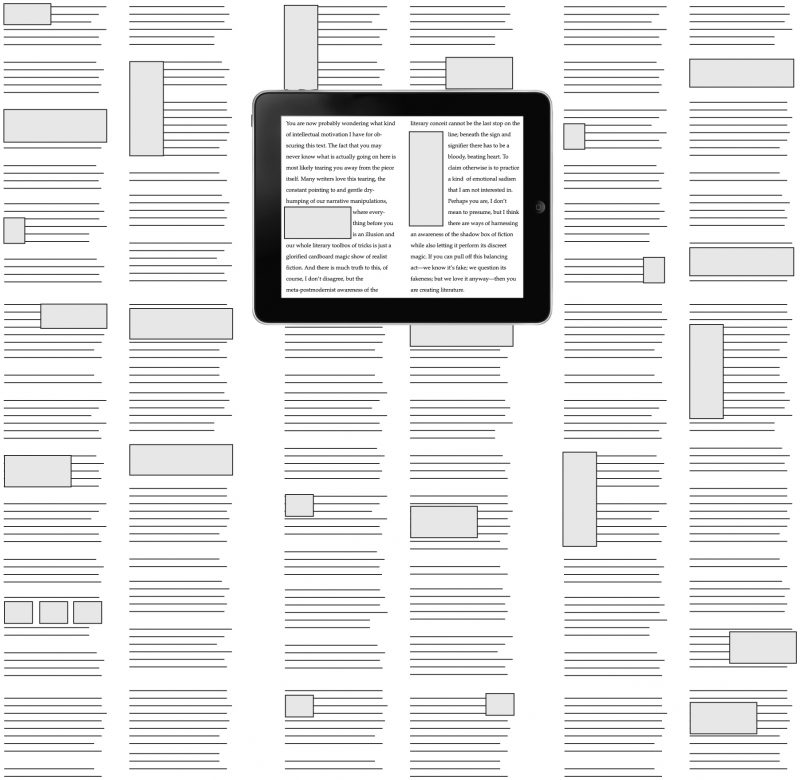

And then a funny thing happened. Eight years later, my first novel, The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet, came out, concerning an obsessive twelve-year-old cartographer liv-ing on a ranch in Montana. And you know what? It was essentially an exploded hypertext novel. I had circled back around to the very thing I disdained. The key difference here appeared to be in the explosion part. In Spivet, all links had been expanded and mapped out on the page, and somehow the technology of the printed page really mattered in this regard—it was important to see these links laid out on a page spread, as if the reader were viewing an instruction manual of how to put together a person’s mind. At the time, this formulation was a gut reaction to the needs of the character and the story, but the process of writing that book has since given me insight into my allergy to the hypertext stories of the ’90s and perhaps some useful counsel when the time comes to reach for our Immerso-Goggles™.

As writers, we are constantly battling hidden and less-hidden subtexts. The art of cultivating narrative is essentially an art of choosing what not to say and how not to say it. By allowing the reader to actively navigate these subtexts (at least those that are provided), hypertext fiction promised to dismantle the autocratic paradigm of suppression and, in a subversive, post-Freudian maneuver, invite the reader/navigator to become a collaborator of his or her own unconscious. The problem with this model is that while readers like the idea of control, what they really want is just a taste of this control and then they want to be shown the goods.2 With Spivet, I was attempting to straddle this line between volition and orchestration. It was up to the reader to break the narrative flow by following the arrow into the subconscious arena of the margins, but in doing so, he or she also knew this disruption was scripted and somehow purposeful to a larger whole.

As Nicholas Carr points out in his book The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, we face a world increasingly built on the currency of disruptions—tumblruponmydeliciousfarkdiggandtwitterallovermyfacebook—that seems destined to rewire our brains to the point where it will be impossible for us to finish Moby-Dick anymore. Carr reminds us that even David Foster Wallace, the guru of narrative digression and recursion, declared, in his Kenyon commencement address: “‘Learning how to think’ really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. Because if you cannot exercise this kind of choice in adult life, you will be totally hosed.”

I’m not going to enact the moralist hand-wringing routine over our dwindling capacity for attentiveness (which may be our greatest asset), but given the trajectory of things, it does seem important for fiction writers to take a step back and survey the task at hand.

For one, we are, and will continue to be, storytellers. And successful storytelling will continue to rely upon certain pillars: the slight, gnawing fishhook of suspense; the fleshing out of complex, world-weary characters; the withholding of information; the measured lusciousness of language; the upending of expectation; the shifting of pace, mood, and scene; that counterweight loneliness of the final sentence.

Let us also not forget that despite the great movement to share all aspects of our lives via our magical devices, the actual act of reading is (and always will be) an intimate act. We read and create our story-worlds in the infinite privacy of our own minds. It is my hope that the iPad and the inevitable flood of touch-sensitive e-books may soon be able to embrace the intimacy of the act by giving us an immediate, palpable story-window that can literally be held and brushed up against. The tactility of touch screens may finally make overlapping narratives accessible where other technologies have failed. Instead of clicking a link with a mouse, you literally touch a word, conjuring a note card that can be easily expanded, collapsed, or filed away.

This dance between form and content will continue to shift and shiver: a story about a blind woman growing up on the sea may include quiet moving images of knots and wind speed, either embedded on the page or floating above it, and in moments where our protagonist is reading herself, braille dots may ghost in behind the letters of the story, almost imperceptible to the eye. The possibilities are endless. So, too, are the opportunities for restraint. Indeed, knowing when to harness the power of the new media and when to let the simplicity of text work its magic may well be our greatest challenge as we continue to erect the walls of our labyrinths, searching for a solution that will never come.

2.

2.