I.

I thought I had The Canyons’ number.

Last winter I picked up Lunar Park, Bret Easton Ellis’s faux-memoir-slash-Stephen-King-gorefest-rip-off-slash-surprisingly-moving-story about fathers and sons. In it, the central character, Bret Easton Ellis, writer of Less Than Zero and American Psycho, is working on a new book called Teenage Pussy, which will, he promises, contain “endless episodes of girls storming out of rooms in high-rise condos and the transcripts of cell phone conversations fraught with tension and camera crews following the main characters around as well as six or seven overdoses… There would be thousands of cosmopolitans ordered and characters camcording each other having anal sex and real-life porn stars making guest appearances. It [would] make Sodomania look like A Bug’s Life.” At the end of this description two words were flashing in my brain: oh and wow. I headed on over to Amazon, all set to place a rush order. Teenage Pussy, though, wasn’t available on that site or any other. Turned out it was a fictional work of fiction. Tough luck for me, I guess.

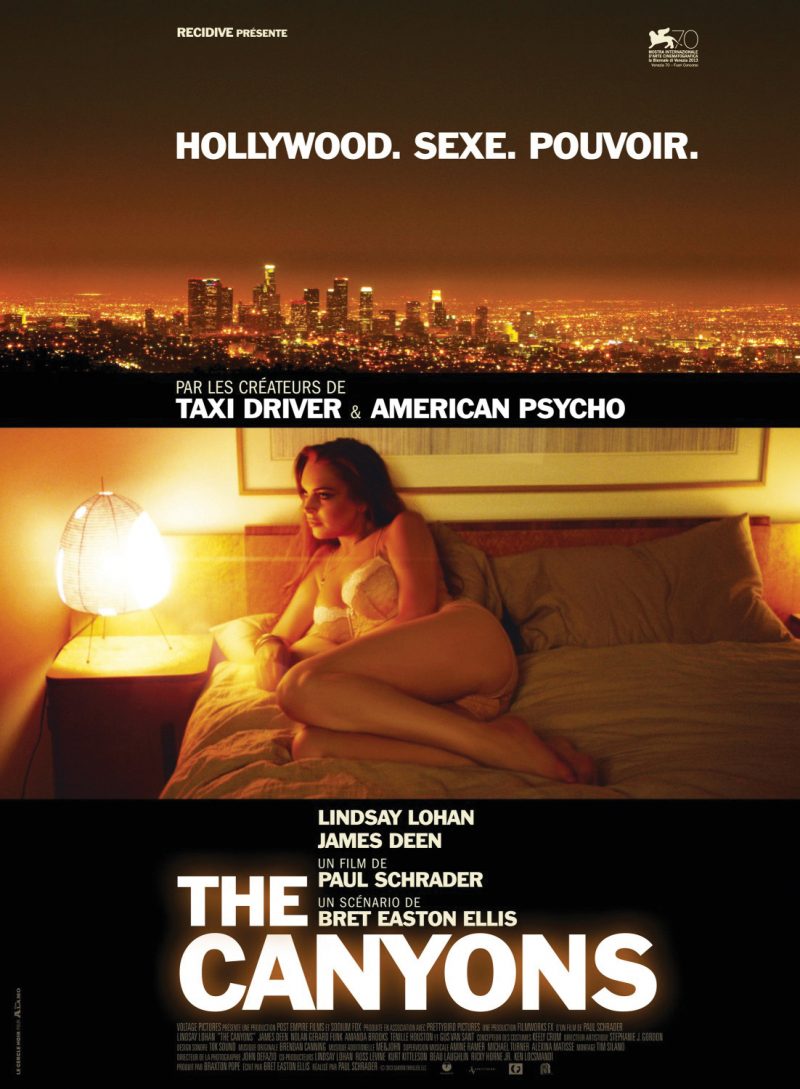

A few months later I came across a piece in the New York Times called “Here Is What Happens When You Cast Lindsay Lohan in Your Movie.” The article chronicled the troubled young actress sometimes keeping her shit together though mostly not while shooting what has been described variously as an “erotic thriller,” an “L.A. neo-noir,” a “psychosexual drama,” and “cinema for the post-theatrical age,” scripted by Bret Easton Ellis, directed by Paul Schrader, starring, in addition to Lohan, porn star James Deen, and financed in some crazy way I only vaguely understood but that seemed mainly to involve spit, string, and the popular funding-platform Kickstarter. As I raced through the story, my excitement mounting, I became convinced that this movie (The Canyons) was that book (Teenage Pussy).

Art wasn’t just about to imitate art. Art was about to cannibalize art, then wear art’s skin like a flashy new suit.

II.

Bret Easton Ellis is modern literature’s little rascal supreme. He seems to do things for no reason other than the fun of it. Take, for example, the many references in his books to his other books, references made in such a super-subtle yet obsessive way he could be doing it only to amuse himself. His minor characters are often recurring. Sean Bateman, for example, one of the protagonists in The Rules of Attraction, has, it is glancingly mentioned, an older brother, Patrick, the gifter of a brown Ralph Lauren tie about which Sean has ambivalent feelings. Patrick then lands the lead role as the Psycho who also happens to be an American in Ellis’s next work. Ellis did the same thing with Victor Johnson, Lauren Hynde’s mostly offstage boyfriend in The Rules of Attraction, moving him from the periphery of that novel (he’s backpacking through Europe for much of the narrative) to front-and-center in Glamorama. Ellis even gives him a stage name, Victor Ward—which is stronger, more macho-sounding, and, with fewer syllables, fits better on a marquee—as is commensurate with his change in status from bit player to star. What or whom, one wonders, did these characters have to do in order to secure their big breaks? If any writer would have a casting couch for his fictional creations, it would be Ellis.

And the little rascal thing is why Ellis is such a terror on Twitter. He picks fights with girls (Kathryn Bigelow, he said, would rate no higher praise than “mildly interesting filmmaker” if not for the fact that she is “a very hot woman”); with dead guys (he regularly puts dents in the halo of David Foster Wallace); with gay people—and he is one, sort of!—proclaiming the casting of Matt Bomer for the lead in Fifty Shades of Grey “absolutely ludicrous,” as the role requires a performer who is “genuinely into women.” You talk trash, you’re going to make people mad. Ellis is all right with that. He’s cruising for a bruising, he knows it, and he doesn’t bitch when he gets one. For being a meanie to Wallace, he was branded “jealous,” “a has-been,” “a dumb motherfucker,” and worse, all of which he shrugged off. He may be a pot-stirrer and a pain in the ass, but he’s not a whiner.

For me, his refusal to repent or back down is one of his most impressive features. Sure, after the controversy surrounding the Bigelow comments refused to subside, reach–ed unignorable proportions, he did issue an apology on the Daily Beast. It wasn’t so much for what he said, though, as for the way he said it. And it was more of an I’m sowee—“It is what it is,” he stated at one point—than a please forgive me. And when the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) uninvited him to its media awards and asked him not to tweet about it, he promptly tweeted about it, and a few weeks later wrote a witty, angry, devastating little piece for Out magazine concerning the fascist tendencies and general humorlessness of the organization, which he dubbed “the Gay Gatekeepers.”

Nor is Ellis nervy only in his private life, or at least the portion of his private life conducted in public, over Twitter, and in newspapers and magazines. His novels, whatever you think of them, couldn’t be accused of a lack of boldness or energy or pulse. Or guts. (American Psycho wasn’t just dumped by its first publisher, Simon & Schuster, and boycotted by the National Organization for Women, it also inspired actual death threats filled with detailed descriptions of tortures that would be inflicted on his living body and then his corpse. Ellis didn’t bat an eye.) The novels couldn’t have been written by anyone else, either, though Glamorama might have been written by an Ellis parodist. And because they’re different, they’re frequently misunderstood. The reviews he gets are often more than simply not good; they’re flat-out disrespectful. I’m looking at you, Michiko Kakutani.

III.

Since making mischief is clearly Ellis’s idea of a good time, I assumed that’s what he was up to with The Canyons: penning a script for a movie that is an adaptation of his fictional novel that his fictional self never actually completed (the character Bret Easton Ellis in Lunar Park suffers from writer’s block). Not that he was copping to it, of course. The funding on his previous project, another collaboration with Paul Schrader, Bait, a revenge thriller about class rage and bloodthirsty sharks, had fallen through at the last minute. “[Schrader and I] were never going to go through it again,” he vowed. They’d had it with executives who mistook themselves for artists and movies made by committee. Self-financing seemed the only way to save their marbles and their cool. And as Schrader pointed out to Ellis, “What you do isn’t that expensive. Beautiful people, nice rooms, bad things, and sharp talk. How expensive is that?” Ellis got to work. “I began to basically construct a Paul Schrader script,” he said.

My suspicion, however, was that though he was hanging back and acting low-profile, embracing his status as the humble writer, a mere tool (in Imperial Bedrooms, the protagonist, Clay, in the same line as his creator, is asked if he knows the one about the Polish actress, the punch line being she came to Hollywood and fucked the—wait for it, wait for it—writer), the instrument of the director and of the director’s vision, in fact he was the controlling intelligence behind The Canyons. First off, this movie is just so perverse an undertaking, and in such a specifically Ellisian way. It’s all very post-Empire, a concept Ellis invented by way of Gore Vidal and one he declines to define directly but rather allusively, through example. Empire is Madonna. Post-Empire is Lady Gaga. If Ellis won’t attempt a direct definition, though, I will: America, as an Empire, is finished, and post-Empire artists make their art out of Empire detritus, i.e., they are the cultural equivalent of Dumpster divers.

I can’t imagine a project that follows these guidelines more assiduously than The Canyons. No one involved in the movie is quite respectable, including Ellis, a major American writer who’s never won a big-time literary prize. And while Schrader has been involved in several movies with monster reputations—he scripted both Taxi Driver and Raging Bull—his work has yet to be been sanctioned by the Academy.

Then there are the movie’s stars. You’ve got James Deen, porn-industry It Boy, as the male lead; such outré casting is possible only because the movie was being financed not in the traditional way, through a studio, but, as already mentioned, through Kickstarter primarily, the principals auctioning off everything from cameos to novel critiques to tchotchkes given to them by major-league celebrities (10K would get you the money clip De Niro presented to Schrader during the making of Taxi Driver). Deen was purely Ellis’s doing. Two years ago, Ellis tweeted, “in the canyons james deen as christian would have to do full frontal nudity and scenes with both girls and guys.” Deen tweeted back a single word, “party,” and it was on. (Or almost on. Schrader still had to be convinced that the X-rated Critics Organization’s Unsung Swordsman of the Year, performer in over four thousand adult movies—“That’s a lot of pool boys and pizza delivery men,” the director understated—was the thespian for the job. It was on eventually, though.) Ellis has called Deen his muse and stated that when he wrote the script he was “picturing no other actor.”

You’ve also got Lindsay Lohan. According to the Times piece, after Ellis got his way with Deen, he tried to veto the casting of Lohan. Schrader and producer Braxton Pope had to talk him into the hire. Unh-uh, I was thinking as I read this. He pulled a fast one, I was thinking. He was letting Schrader and Pope believe they were in control, running the show, but au contraire, I was thinking. He was working them and it worked, I was thinking. Lindsay Lohan is an ingenue from hell, Ellis’s kind of ingenue: a freckle-faced cutie-pie turned zonked-out zombie sexpot seemingly overnight, a Disney darling who now looks like she should be under contract at Vivid, a rising star at the tail end of a spectacular flameout. But she has a swagger to her, too, an I am not ashamed defiance. And it’s this fundamental refusal to shape up, to get her act together, to be a Nice Girl, that finally redeems her. She’s the female Charlie Sheen, basically, the actor Ellis wrote so admiringly about in Newsweek in 2011, referring to Sheen as “the new reality, bitch,” and to Sheen’s very public meltdown as “performance art.” Ellis is going to put the kibosh on Lohan? Not a chance in hell.

And what was up with him partnering with Paul Schrader on such a high-libido, ooh-baby-type project? Schrader, after all, is the guy who made Hardcore, a movie that Pauline Kael savaged for its “frigid sensationalism,” famously concluding her review with the line “For Schrader to call himself a whore would be vanity: he doesn’t know how to turn a trick.” Essentially, she was informing Schrader, along with every single reader of the February 19, 1979, issue of the New Yorker, that he was sexually inept, certainly as a director and very likely as a man as well. He was a prig, a fuddy-duddy, a cold fish, almost pathologically unsuited to the task of telling a tale centered on erotic obsession, erotic degradation, erotic anything.

To me it was unlikely to the point of inconceivable that someone as pop-cultured as Ellis would be unaware of Pauline Kael’s review when he got together with Schrader, especially since he once quoted her in a tweet: “Hollywood is the only place where you can die of encouragement.” So, unless Ellis was following the Andy Warhol dictum about getting it “exactly wrong,” which was, actually, precisely what I suspected he was doing, Schrader seemed like a willfully—nay, deliberately—bad choice for the subject matter.

Then there was The Canyons’ tagline: “It’s not The Hills…” What was an allusion to the undeniably compelling and even less deniably pea-brained MTV reality show doing on the movie’s poster? Ellis must’ve put it there. (Clay, the writer stand-in character in Imperial Bedrooms, watches it, so it’s obviously on Ellis’s radar.) Why? Because he was eradicating distinctions. A half-hour program in which a camera crew followed around a couple of listless Southern California girls as they made the smallest of small talk—what Ellis characters would sound like if he wasn’t writing their dialogue—and a film scripted by the guy who produced what is arguably the definitive novel of the 1980s, directed by the guy (semi) responsible for numbers 24 and 47 on the American Film Institute’s 100 Greatest American Movies of All Time list? Same difference. Movie stars are passé. So why not use a fallen one and an adult one? In fact, movies themselves are passé—done, over, next. So why not turn the movie into a reality show? Lohan’s life already is one. She’s been a tabloid cover girl since before she was legal, the paparazzi dogging her every move, her most banal activities not just newsworthy but headline-worthy: LINDSAY LOHAN DUCKS UNDER A TABLE. DID LILO COP A FUDGIE THE WHALE??? (FYI, a Fudgie the Whale is a type of ice cream cake made by Carvel.) LINDSAY LOHAN SPOTTED SMOKING ON BALCONY OF MALIBU REHAB FACILITY.

Or turn the movie into a porno? The Canyons contains extensive nudity and a foursome. So it’s already in soft-core territory. And porn would appeal to Ellis for reasons in addition to the obvious ones. The porn industry is without question a post-Empire conceit. There’s a hipness to it, an honesty. It’s Hollywood stripped of the hypocrisy, the arty airs and high-minded intentions. In fact, the two are mirror images of one another, only porn is the fun-house-mirror image, all of Hollywood’s ugliest, crassest features distorted and magnified. Porn performers don’t pretend to be artistes. They’re on-screen purely to serve as objects of fantasy and desire. And porn movies are overtly about what mainstream movies are covertly about: exploitation, voyeurism, commercialism, sex for fun and profit, big lips and bigger tits, fake tits and faker lips. The rumors floating around about how it works in Hollywood, the things actors and actresses have to do in order to get the part, are the parts for porn actors and actresses. The porn industry is up front about its sleaziness. And it loves to kid its twin brother, a scumbag, too, but pretending to be respectable, puckishly churning out spoof after spoof of Hollywood’s most earnest offerings: Forrest Hump, Schindler’s Fist, Drilling Miss Daisy, The Curious Case of Benjamin’s Butthole.

So with The Canyons you’d have a movie, but you’d also have the reality version of the movie, and the porno send-up as well. It would be three for the price of one.

IV.

Like I said, I thought I had The Canyons’ number. Turns out I didn’t. Or rather, I did and I didn’t. I did have The Canyons’ number about certain things. Ellis knows his Pauline Kael, for example. When we met at his apartment in West Hollywood, I saw that the shelves in his office didn’t hold just her book of greatest hits, For Keeps: Thirty Years at the Movies, or her book of capsule reviews, 5001 Nights at the Movies, but her book books, too.

Other things, though, I was wrong about. Lindsay Lohan, for one. Ellis really did try to block her casting initially. When I asked him why, he said, “I didn’t want her, for the same reason that Paul didn’t want James [Deen]. Because I thought it would backfire. And I liked Tara [the character Lohan plays]. I was protective of her.” His explanation was surprising in two ways: for its lack of cynicism and its essential sweetness. (He had tender feelings for Tara! Tara, a quasi-starlet and straight-up gold digger!)

More surprisingly, I was also wrong about him being the brains behind the “It’s not The Hills…” slogan, even though he confessed that he’d “watched every episode, some seasons twice.” Turns out that The Hills reference was all Schrader. Schrader, who didn’t see his first movie until he was eighteen because his Dutch Calvinist family regarded them as sinful and who cites the Bible and The Pilgrim’s Progress as his two biggest influences, apparently is an avid follower of the breakups and makeups, high jinks and low jinks, of L.C. and Lo and Audrina. Of Brody and Justin-Bobby. Of Speidi.

Then again, when it came to Schrader, I missed the mark all over the place. I blame it on my relationship with Pauline Kael, which is passionate and obsessive and has been going on since my jailbait years and exists purely in my imagination.

First, though, a word about the relationship between Schrader and Pauline. The two went way back, starting in his undergraduate days. She functioned as a friend and mentor, almost a mother figure, talking him out of becoming a minister and into becoming a movie critic, using her influence to get him admitted into UCLA film school, and then, later, a job reviewing for the Los Angeles Free Press. She cooled a little when he tried his hand at screenplays. She cooled a lot when he began to direct those screenplays.

That Schrader had once used her living-room sofa as a bed gave Pauline an excellent excuse for recusing herself from reviewing his work. She didn’t take it, though. She opened her assessment of his first movie, Blue Collar (1978), with a fast jab: “Blue Collar has to be one of the most dogged pictures ever produced… the ultimate overdue term paper.” Next came a series of body blows as she took him to task for his “nighttime fatalism,” his “jukebox Marxism,” and for “impos[ing] his personal depression [!] on characters who, in dramatic terms, haven’t earned it.” And then, in case by some miracle he was still standing, she delivered a closing knockout punch: “People can be impressed by a movie this low in entertainment value; they can assume that it’s thinking of higher things. But chances are that when Paul Schrader gets his bearings as a director he’ll put his manipulative cynicism to more sparkling uses.” And that was Pauline holding back!

Hardcore, Schrader’s next feature, was where she really let him have it. (That last line, already quoted, has to be the kiss-off of all kiss-offs.) As subpar and disappointing as the movie might have been—and Schrader himself admitted he was never happy with it—it’s difficult to believe he was getting a fair shake. Not that giving one of those ever interested Pauline, who famously referred to objectivity as “saphead objectivity.” Still, this review was beyond subjective, beyond biased. In fact, this review wasn’t a review at all. It was an indictment. No, even indictment is too mild a word. What was going on in this piece of writing was a whole lot darker and weirder and wilder than that. On the surface, Pauline appeared to be coolly logical, offering a point-by-point takedown of the film, articulating everything that was wrong with it in terms of style, sensibility, and execution in her crisp, lucid, no-fuss prose. But underneath that icy, formal rigor there was a heat, an excitement. Listen closely and you could practically hear the sound of panting. This was passion. This was bloodlust. A whore who doesn’t know how to turn a trick? She was feminizing Schrader and then telling him he was a flop at being a girl, too. It was the kind of analysis that didn’t cause just depression but impotence as well. Who but Pauline would dare?

I’m giving all this telenovela backstory—Pauline’s feelings about Schrader, my feelings about Pauline—as a way of explaining why I was unfamiliar with much of Schrader’s oeuvre. Or, to put it more succinctly: yada yada yada, I’d never seen American Gigolo.

I watched it the day before Schrader and I were scheduled to meet. By the time the credits rolled, my jaw was swinging on its hinges. I was knocked out by the movie qua movie, certainly. But also now I understood what Ellis was doing with Schrader. This match wasn’t, as I’d originally thought, a perverse experiment in odd couple-hood. It was a love match. The two are soul mates, their sensibility not just shared but very nearly the same.

American Gigolo has a plot in the same way that, say, Imperial Bedrooms has one. Julian Kaye, a high-priced hustler with even higher-priced tastes, falls in love with a senator’s wife and nearly becomes the patsy in a murder case—but it’s not really what the movie’s about. What the movie’s really about is mood and atmosphere and menace; about striking a pose and holding it so the terror doesn’t show; about designer labels and dressing to kill or be killed; about Los Angeles as a city that looks like a dream but feels like a nightmare. Even the carnal qualities of Schrader’s movie and Ellis’s books are similar: heterosexual on top but only on top, underneath ambiguous leaning toward gay. So, too, with their affects, which I find strangely emotional and upsetting, soulful, as well, surprising in works ostensibly so concerned with surfaces. “The better you look, the more you see,” says Victor Ward again and again in Glamorama, a thesis the structure of the book doesn’t quite bear out. And my sense is that the poignancy creeps up on you because Ellis’s protagonists, like Richard Gere’s Julian, initially seem to be the final word in narcissism, but are, it turns out, self-absorbed out of fear rather than choice—they’re afraid to connect or don’t know how to—and come off as spiritually bereft when in fact they’re in spiritual crisis.

American Gigolo was an undeniable influence on Less Than Zero (Less Than Zero even has a male prostitute named Julian), and Ellis doesn’t try to deny it. Of the movie he said, “It was a revelatory look at LA, the way [Schrader] photographed it, so gorgeous, so druggy, so gay. And Richard Gere was so beautiful. I’d seen women photographed like that before but never a man. It was radical and unnerving at the same time.” He acknowledged, as well, the overlap of his sensibility with Schrader’s, but quickly added with a laugh, “Obviously I’m not so Calvinistic.” When he said it, I laughed back and nodded, because, yeah, of course, obviously.

But, on reflection, maybe no, not of course. Ellis—an original Valley Boy, a Literary Brat Packer and bud of Jay McInerney’s, an almost-threesome partner of Molly Ringwald’s and Rielle Hunter’s—is an irreverent, ironic writer and secular to the point of profane. At the same time, though, there’s a religious quality to his work, something fevered and ferocious, borderline messianic. And often in his books there’s a need for spiritual purification so powerful it manifests itself in physical violence à la Travis Bickle’s bloodbath shootout at the end of Taxi Driver. The most obvious example is American Psycho, about an investment banker by day, a homicidal maniac the rest of the time, the pressure inside him mounting until he erupts in a bout of fury that’s positively biblical in its no-holds-barred savagery; but it’s there in Glamorama and Lunar Park and Imperial Bedrooms, too. Ellis’s protagonists are also as solitary as Travis. The Bret Easton Ellis of Lunar Park is verbal and charming, a husband and father and famous writer, a party animal and professional provocateur—almost a cartoon extrovert—but at the same time always moving in the direction of being alone, of asceticism. “People are afraid to merge.” These are the first five words of Ellis’s first book, and they could be the first five of every subsequent one.

V.

All of this brings us to the million-dollar question: how’s the movie? According to the critics, not so hot. (“A dispiriting, unpleasurable work,” raves the New York Times. “Corners the market on lethargy,” lauds the Los Angeles Times. “As much fun… as… Chernobyl,” coos the New Republic.) Whatever. I enjoyed it. It’s trash but it’s pretty good trash—lively and entertaining—and it’s trash that’s not pretending to be anything else. The plot’s like a compilation of classic noir plots without suggesting any one in particular, all the tropes present and accounted for: there’s the Woman With a Past, the Sexy But Dangerous Boyfriend, the Sweet, Lunkheaded True Love; there’s a romantic triangle with angles so sharp somebody gets cut, bleeds to death; there’s a frame-up and two kinds of behavior, bad and worse.

The premise beneath the premise, too, is an intriguing one. This is a movie that’s hyper-aware of movies as a medium that has one foot and four toes in the grave. (The only way it could be any more aware, in fact, is if it made that death its explicit subject.) The credits, both opening and closing, play out over abandoned, trashed-looking suburban multiplexes; the characters, all Hollywood bottom-feeders involved in the production of a low-budget slasher film, are in the business not because they’re passionate about the chosen mode of expression of Ozu, Renoir, and Welles, but because they want fame or money or sex partners, a way to pass the time, break up the monotony of the gym and the mall; and the scenes are filled with dialogue like this: “I guess [movies are] just not my thing anymore.” Basically, The Canyons is a movie about people who make movies and work in movies and would do anything to be in movies and yet don’t give a shit about movies.

The performances in The Canyons are also solid. In spite of a distractingly odd makeup job (it’s like she didn’t wash her face after appearing as Elizabeth Taylor in Lifetime’s Liz & Dick, kept the cat eyes and batwing lashes), Lindsay Lohan does an effective job of acting alternately smoldering and petrified. James Deen is convincing as a snaky-sexy sociopath with daddy issues. Gus Van Sant, who essentially predicted Lindsay Lohan and TMZ and US Weekly with his 1995 film To Die For, is as unsettlingly weird as you could hope in his cameo as Deen’s shrink. And Nolan Funk, as the male ingenue—well, he looks good without a shirt on.

Looking good, too, is the movie in general. I’d never have guessed it was made on such a skimpy budget. Schrader’s visual style is spare and streamlined, yet somehow lush at the same time. And if the movie didn’t linger in my mind, never once was I bored or impatient with it. Here’s the assessment Ellis gave me: “I’m totally fine with it. I don’t have negative things to say. It’s gotten better as Paul’s edited it. But I can certainly imagine people feeling that it was a Paul Schrader and Bret Ellis film and expecting something a lot slicker and wilder. I can understand a certain kind of disappointment.” That about covers it so far as I’m concerned.

In any case, I’m not sure how much good or bad really figures here. Not for Ellis, at least. All the tomato throwing has, I’d guess, been harder on Schrader. My sense from my talk with him is that he saw The Canyons as a legitimate contender, up to the standards of his past work. Ellis was under no such illusion. In an interview with the Aesthete magazine, he said, “How we made it is the real subject of The Canyons for me.” He’s dead-on. The making of the movie is the art. The movie itself is, finally, incidental, beside the point, which is why the criticism of it is, too. Or, as Bret Easton Ellis—the character, not the person—says in Lunar Park, “Deal with it, rock ’n’ roll.”