The woman looks into the camera with an expression somewhere between contentment and apathy. With her thick brown hair and floral dress, she could pass for Party of Five–era Neve Campbell, or a blowsier Natalie Merchant. She is holding a sign on which she has written in Magic Marker: IT’S OK FOR YOU TO THINK I’M NOT OK BUT I AM. Nothing in the photo suggests the presence of a beverage, but it is, nonetheless, an ad for a soda.

The year was 1994—My So-Called Life, Kurt Cobain’s suicide—and the Coca-Cola Company, smarting from a recession, was attempting to reach a new demographic of disillusioned young people known as Generation X. The previous year, Coke CEO Roberto Goizueta had rehired Sergio Zyman, the Mexican marketing guru, despite the fact that his last brainstorm, New Coke, had nearly toppled the company. Nevertheless, Zyman was tasked with overseeing a new brand that would appeal to the MTV generation, one inoculated against the standard advertising language of shiny packaging and jingles.

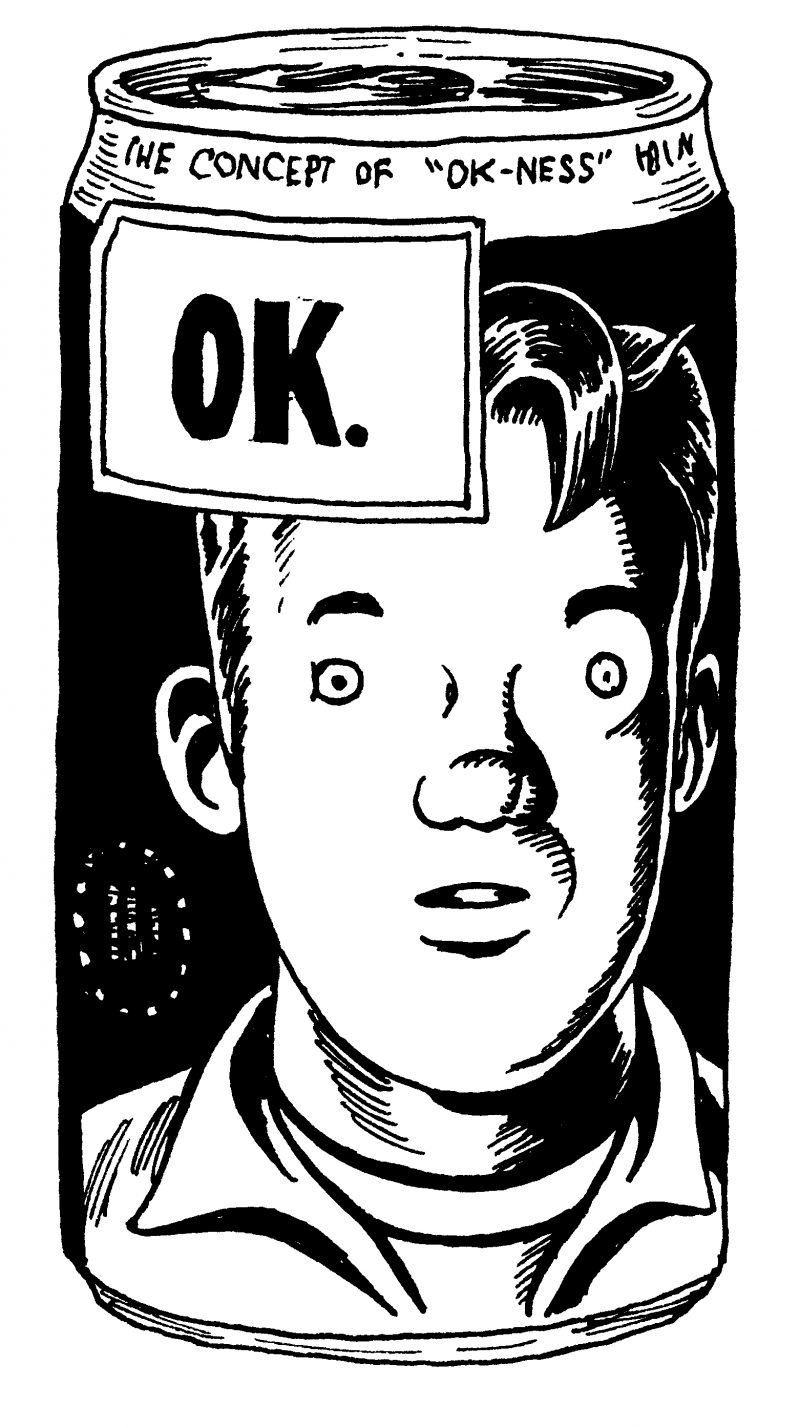

The result was OK Soda. As Mark Pendergrast writes in For God, Country, and Coca-Cola, “the drink was deliberately positioned to be blasé. It wasn’t exciting, delicious, or sexy. It was just OK.” Where other brands courted teens with empty promises—This sneaker will change your life—OK Soda appealed to their innate skepticism. “It underpromises,” one Coke executive, Brian Lanahan, told Time. “It doesn’t say, ‘This is the next great thing.’”

Depending on whom you ask, the product was either groundbreaking or doomed: a jaded soda marketed to people distrustful of marketing, with accompanying advertising designed for people who hated advertising. When it launched, Zyman predicted that OK Soda would garner a billion dollars and 4 percent of the US soft-drink share. But by 1995 it was off the shelves: another Zyman misfire. Twenty years later, it maintains a cult following, with old poster art fetching hundreds of dollars on eBay. What OK Soda represents is surely failure—of a giant corporation pandering to the margins—but the kind of failure so brazen, tone-deaf, and strange that its legend survives as a kind of marketing performance art, utterly endemic of its time.

When OK Soda was introduced, of course, Coke executives were certain they had it right. Drawing on a study from MIT, the company had pinpointed what Generation X was all about. “Economic prosperity is less available than it was for their parents,” Lanahan theorized. “Even traditional rites of passage, such as sex, are fraught with life-or-death consequences.” Tom Pirko, a Coke marketing consultant, told NPR, “People who are nineteen years old are very accustomed to having been manipulated and knowing that they’re manipulated.” He described the soda’s potential audience as “already truly wasted. I mean, their lethargy probably can’t be penetrated by any commercial message.”

How to sell soft drinks to such people? The answer was to embrace the angst. Coke turned to Wieden + Kennedy, the ultra-hip Portland, Oregon, ad firm that had devised Nike’s “Just Do It” campaign. The agency’s pitch has become the stuff of soda lore: research had shown that Coca-Cola was the second most recognized term in the world. The first was OK, which, the firm pointed out, was also the two middle letters of Coke. So why not combine the two? The drink was christened OK Soda, and its semi-reassuring motto was “Things are going to be OK.”

The soda would be introduced in nine test cities, including Gen-X strongholds like Austin, Seattle, and Denver. Instead of showing beautiful people drinking soda on the beach, the ads would feature surly black-and-white graphics that barely acknowledged the product at all. The idea was to create the feeling of a movement—and, like any movement, OK Soda had its own manifesto. Its precepts, which appeared on and even inside the cans, were like slacker koans:

1. What’s the point of OK? Well, what’s the point of anything?

2. OK Soda emphatically rejects anything that is not OK, and fully supports anything that is.

3. The better you understand something, the more OK it turns out to be.

4. OK Soda says, “Don’t be fooled into thinking there has to be a reason for everything.”

5. OK Soda reveals the surprising truth about people and situations.

6. OK Soda does not subscribe to any religion, or endorse any political party, or do anything other than feel OK.

7. There is no real secret to feeling OK.

8. OK Soda may be the preferred drink of other people such as yourself.

9. Never overestimate the remarkable abilities of “OK” brand soda.

10. Please wake up every morning knowing that things are going to be OK.

The OK manifesto was written by Peter Wegner, the campaign’s associate creative director. Wegner has since quit advertising and is now a multimedia artist living in Berkeley, California. When I talked to him recently, he sounded like a misfit philosopher. “The nature of OK-ness is that it comes and goes,” he explained. “It was just an intriguing notion of something you may have glancing contact with if and when you got around to drinking the beverage.” Even now, his work inspires the kind of scrutiny usually reserved for Pynchon novels. “Every once in a while, someone will send me a link to a professor contemplating some odd little cul-de-sac in the brand—just some little footnote curled up within a footnote.”

Wegner’s collaborator was Todd Waterbury, now the executive creative director at Target. To hear Wegner and Waterbury tell it, the campaign was the work of two punch-drunk troublemakers trying to amuse each other from adjoining cubicles. “It really was the most fun we’ve ever had making work,” says Waterbury, who was in his late twenties when he worked on the account. If Wegner was the campaign’s in-house poet, Waterbury was its visual mastermind. Poaching from indie culture, he hired graphic novelists from the Fantagraphics stable, including Daniel Clowes (who went on to publish Ghost World) and Charles Burns (longtime Believer cover artist), to draw a series of unsmiling Gen-X portraits that resembled WANTED posters.

Clowes remembers getting a FedEx package one day with a mock-up of some of his drawings on a soda can. The images were adapted from his graphic novel Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron. The book’s noirish plot involves a snuff film, sexual fetishism, and horny mutants. “I was like, Is this for an office party at Coke or something?” Clowes recalled. “It seemed like some rich guy’s prank.” When he reached Waterbury, he was surprised to learn that the product was real. “I knew full well that what they were trying to do was not possible, that you could not market to cynical hipsters by being cynical and hipsterish.” But the pay was good—more than Clowes had made on his last five comics—so he took the job, not imagining that the product would ever see the light of day. In a reflexive act of subversion, he drew his OK Soda mascot with the eyes and nose of Charles Manson. “They made me sign all this nondisclosure paperwork and stuff,” he said, “but nothing ever said, ‘Don’t put a mass murderer on the can.’”

Not that Waterbury and Wegner weren’t planning their own kind of insurrection. The cans and posters were scrawled with absurdist messaging, including so-called “coincidences”—surreal stories, written by Wegner, about OK Soda drinkers experiencing peculiar twists of fate. Coincidence number fourteen: “The night he first tried ‘OK’ Soda, Rick B. of Aurora, Colorado, put a full can under his pillow and went to sleep. He dreamed he was crawling through an endless gravel pit, parched with thirst. When he awoke, his thirst had disappeared, and he felt strangely satisfied. Note: the can of ‘OK,’ still unopened, was empty. This is only a coincidence.”

Even stranger were the campaign’s interactive elements, including a hotline, 1-800-I-FEEL-OK. Callers would follow a chain of true/false prompts (“I’d rather be a flower than a shovel, but I’d rather be a shovel than dirt”; “I like cardboard”), inspired by the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. You could also leave messages describing your own “coincidences,” with the disclaimer that “your comments may be used in advertising or exploited in some other way we haven’t figured out yet.” From a caller in Arkansas: “I started drinking OK two days after my boyfriend and I broke up, and ever since I started drinking it, bad things happened to him. He even broke his leg. That’s pretty good.” At one point, Wegner was getting daily stacks of transcribed responses three or four inches high. Some reports even had it that OK Soda was planting its own hostile messages in an effort to foment faux backlash. From Pam H. of Newton, Massachusetts: “I resent you saying that everything is going to be OK. You don’t know anything about my life.”

At the same time, Coke mailed out promotional chain letters featuring more “coincidences.” One of them described a man called Paul S., of Grafton, North Dakota, who followed the letter’s instructions carefully. “Within a week, he found his vocabulary had significantly increased. Within two weeks Paul was, in his own words, ‘No longer shy.’ And within a month, he’d appeared on nationally syndicated talk shows as an unlikely sex symbol.” Recipients were urged—somewhat threateningly—to keep the chain going. “Imagine how crazy that made the phalanx of lawyers in Atlanta,” Wegner said.

The chain letters then appeared on TV commercials, a concept that was purposefully oxymoronic. “What does it mean to receive a chain letter in the context of a thirty-second spot?” Wegner said. “It’s completely, utterly meaningless.” A man’s voice would read an epistolary text in Courier font as it scrolled over a black background. One ad related a “coincidence” from Tom B. of Little Rock, who declined a can of OK Soda and then got stuck in an elevator with a group of third-graders telling knock-knock jokes. In a follow-up ad, the voice-over turned menacing:

To Whom It May Concern:

For the past few weeks, a chain letter promoting “OK” Soda has run on local TV. Despite an outpouring of support, there have been detractors, notably Americans Mad About OK (A.M.O.K.). They have compared our campaign to a virus, and to “the notorious kudzu plant, creeping everywhere, strangling all it touches, needing only dirt to survive.” To this, we can only offer the following response: Things are going to be OK.

Needless to say, A.M.O.K. didn’t exist. The campaign was a series of non-sequiturs, tethered only to one another. If anything, it had more in common with underground art movements than with advertising. Wegner kept books in his office about Dada and Fluxus, which also spelled out their principles in manifestos, and whose notions of “anti-art” gave rise to the idea of “anti-advertising.” “Dada and Fluxus were two historical moments when art didn’t quite know what to do with itself,” Wegner said. “It looked outside itself, laughed at itself, argued with itself, fell all over itself.” The chain letters were reminiscent of “mail art,” started by Fluxus artist Ray Johnson in the ’50s, while the hotline was inspired by the Apology Line, a project by the conceptual artist Allan Bridge. Starting in the early ’80s, Bridge advertised a phone number on flyers around New York, urging potential callers to “get your misdeeds off your chest.”

The “coincidences,” meanwhile, were clearly styled on urban legends, but another reference point was Alcoholics Anonymous. “I had friends in AA and had tagged along to several meetings,” Wegner recalled. “In AA, as in my OK coincidences, you use only first names and last initials. The AA founder is always referred to as ‘Bill W.,’ even though everyone knows his name is Bill Wilson. In the AA testimonials, miraculous things happened to people once they got sober, and apparently it was because they had stopped drinking. With OK Soda, that logic was inverted: the miracle of OK-ness didn’t happen unless you drank the stuff.”

Dada, Fluxus, Alcoholics Anonymous: few ad campaigns boast such influences. Still, what’s shocking now isn’t how outlandish the campaign was but that Coca-Cola went along with it—that is, until it didn’t.

So why did OK Soda fail? The theories are legion. One is that the Coca-Cola Company was too impatient, expecting unreasonable sales numbers for what was essentially a niche product. Between July 1994 and September 1995, OK Soda sold more than one million cases—little more than a rounding error for a multibillion-dollar corporation. Another theory is that cynicism, no matter how clever, is a tough way to sell a soft drink. Waterbury described his concept as “a more relevant version of optimism,” which surprised me. The graphics, which came in stoic grays and reds, look dour, even despairing. Clowes used one image of a man sitting on a rock in Thinker position with an empty word balloon over his head, a scene he describes as “absolute emotional devastation.”

Compare Fruitopia, another brand that Zyman launched for Coca-Cola the same year, in a bid to rival Snapple. With its psychedelic graphics and new-agey flavors (Fruit Integration, Strawberry Passion Awareness), Fruitopia drew on the sunnier side of indie culture: Lisa Loeb to OK Soda’s Daria. The brand remained popular throughout the ’90s, with ads featuring Kate Bush songs, kaleidoscopic fruit imagery, and taglines like “If you can’t judge a fruit by the color of its skin, how can you judge a person that way?” No one ever went broke selling idealism.

Perhaps the target age group was wrong. According to Pendergrast, “millions of kids” called the hotline “just to see what happened.” Preteens, not young adults, may have been OK Soda’s ideal audience: what better way to waste time as a suburban sixth-grader in the pre-internet age than to call a weird hotline over and over? (As Coke discovered, this didn’t translate to sales.) These days, thirty-year-olds are more likely to remember OK Soda than forty-year-olds. For members of Generation Y, it was a chance to play dress-up as Generation X, which couldn’t be bothered to care.

The more likely—and obvious—problem was that the very skepticism that OK Soda sought to exploit ran too deep. As an NPR host asked Tom Pirko in 1994, “If you were nineteen years old and in this category, this market category, wouldn’t you feel a bit manipulated… [that] they were coming after you so blatantly?” However tongue-in-cheek, the message was still coming from a global corporation. Mistrust could breed resentment, even hostility. The graphic artist Shepard Fairey, who thought the ads ripped off his Obey Giant project, tried to sabotage the campaign by posting replacement ads in Boston and Providence that subbed “AG” for “OK” and bore the face of André the Giant.

Of course, it’s the fate of every countercultural group, from hippies to punks, to become a commercial demographic. Generation X defined itself outside the mainstream: it lived on the streets and in garages. Jenny Moore was one of the curators of NYC 1993, a recent exhibit at the New Museum whose thesis was that the year 1993 represented a critical moment of “exchange between mainstream and underground culture across disciplines.” “Everybody was trying to retain this sense of authenticity,” Moore told me. (The exhibit’s subtitle, Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star, came from the title of a Sonic Youth album.) On the top floor, a video timeline showcased 1993’s dizzying cultural output: Björk, Beavis and Butt-Head, Lorena Bobbitt, Waco. Although the exhibit did not include the conception of OK Soda, Moore was reminded of similar efforts to co-opt the counterculture: grunge models in Vogue, AIDS-themed Benetton ads. “Alternative culture became a catchphrase in the early ’90s in a way it hadn’t before,” she said.

Moore, who was nineteen in 1993, grew up in a beach town and remembers seeing a Banana Republic ad showing sexy surfers emerging from the ocean. She recalled the disorienting feeling—a loss of innocence, really—that comes with realizing that your own culture is being “marketed back” to you. A similar paroxysm might have greeted OK Soda drinkers. When presenting his portfolio, Waterbury has juxtaposed the OK Soda ads with a SPIN magazine cover of Beck from the same time: the composition is nearly identical. The point is to dispel the notion that OK Soda misread the counterculture, but the problem may have been less what it got wrong than what it got right. By mimicking youth culture, OK Soda held up a mirror to Generation X, with jarring results: Coca-Cola has your number.

Anaheed Alani, who in 1994 was a twenty-three-year-old grad student, recalled seeing Reality Bites for the first time. “I was like, Fuck you, man! You don’t know what we’re about!” she told me, adding: “I watched it again recently and was like, This is a really good movie and it really does get it right.” Alani is the editorial director of Rookie, an online magazine for adolescent girls founded by the teen fashion blogger Tavi Gevinson. The site often draws on Gevinson’s alt-’90s obsessions (The Virgin Suicides, Winona Ryder). Alani, as resident adult, often vets—and rejects—potential advertisers, who rarely know how to speak to discerning teens. “The minute that they smell advertising,” she says, “they protest vociferously: ‘What the hell is going on here?’”

Alani believes that her generation and millennials have more in common with each other than with those generations in between: namely, a resistance to mass marketing. Still, it’s possible to imagine a contemporary version of OK Soda catching on in the era of viral videos and Tumblr. “We used to think of brands as being this monolithic edifice,” Wegner told me. What Wieden + Kennedy set out to do was the kind of interactive, grassroots marketing that thrives nowadays: what is YouTube if not a hive of “television chain letters,” suitable for forwarding? The absurdist humor of Wegner’s “coincidences” might seem commonplace during commercial breaks for Parks and Recreation. And hipster capitalism doesn’t seem so contradictory in an age when Vice magazine has a show on HBO. Maybe OK Soda was ahead of its time.

Or maybe it just tasted awful. Though you’d be hard-pressed to find a drinkable specimen nowadays, the soda is usually described as citrus-based, with hints of cola and Dr Pepper. In yet another touch of DIY appropriation, its taste was modeled on the “suicide” or “graveyard”—the names of the drink made by mixing together everything from the soda fountain in one cup. At the time, an Atlanta newspaper surveyed teens and found that none of them liked the taste. “It’s better than water,” one said.

Waterbury believes that OK Soda might have sold better had it been a variant on a known flavor—say, a cool root beer. “People would ask, ‘What does it taste like?’” he said. The singularity of the flavor, coupled with the eccentricity of the advertising, was just too hard to grasp. One reason the ads were designed in grayscale was that, even as the campaign gestated, Coke hadn’t decided what color the drink would be. (The final version was reddish brown.) As Wegner put it, “You can’t make people want to consume something they don’t want to consume. The thing they didn’t want to consume was the drink. The thing they very much wanted to consume was the brand. So the product died. The brand lived on.”

So it did. The death of OK Soda coincided with a much bigger phenomenon: the rise of the web, where every arcane interest suddenly had a makeshift community. As the ’90s wore on, OK Soda memorabilia was traded on eBay, and tribute websites sprang up, including the newsgroup alt.fan.ok-soda, which was later swamped by spammers and porn. Like other retro junk, the product had, and still has, an afterlife online. It’s ironic, though, that a brand founded on resistance to advertising turned out to be nothing but advertising. The drink itself was an afterthought.

Clowes never got to see his cans in the store. His hometown of Berkeley, California, was not among the test markets, so the company sent him a six-pack. Hoping to preserve as many as possible, he opened just one can and threw a tasting party for friends. “Each of us got a sip,” he recalled. “We all were like, ‘Eww, what is this?’” For the past two decades, he has kept an unopened can on his bookshelf. A few months ago, he picked it up and found that it was empty. “Like, it had evaporated through the lid somehow,” he said. “Really mysterious. But it’s still sealed. So God knows what was in there.”

Coincidence?