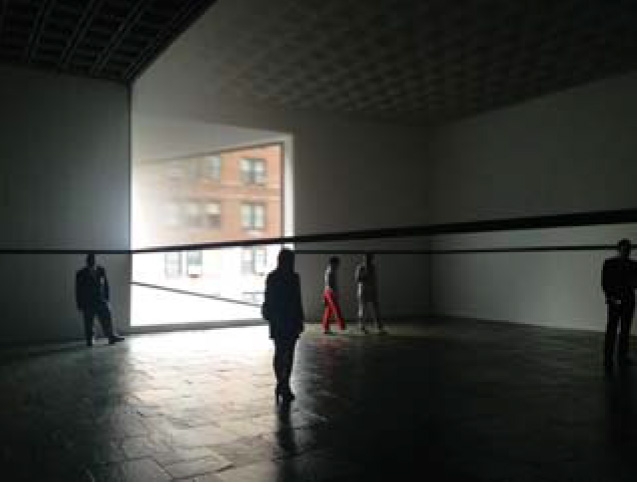

A few months ago, early one midsummer evening, I happened to be up on the fourth floor of the Whitney Museum in New York, experiencing—or perhaps I should say reexperiencing—its restaging of Robert Irwin’s legendary 1977 Scrim veil—Black rectangle—Natural light installation, the piece in which the California artist had emptied out virtually the entire floor, stripping it down to its barest essentials (the dark slate flooring, the gray hive ceiling, that stark trapezoidal window off to the side) and then bisected the resultant vast empty space with a shimmering, pearlescent expanse of white scrim, held taut from ceiling down to eye level by a black metal bar, which in turn echoed the black painted stripe he’d applied to the perimeter of the rest of the room: that and nothing more. A piece, in short, that forced one to find one’s bearings in the midst of a free fall in one’s initial expectations (and to savor the marvel of how one is always having to adjust one’s bearings like that: falling, gauging, steadying)—and then, beyond that, that allowed one to experience the sheer hushed marvel of natural light itself, spreading (as if in a Vermeer) like a tide across the scrim-cut room.

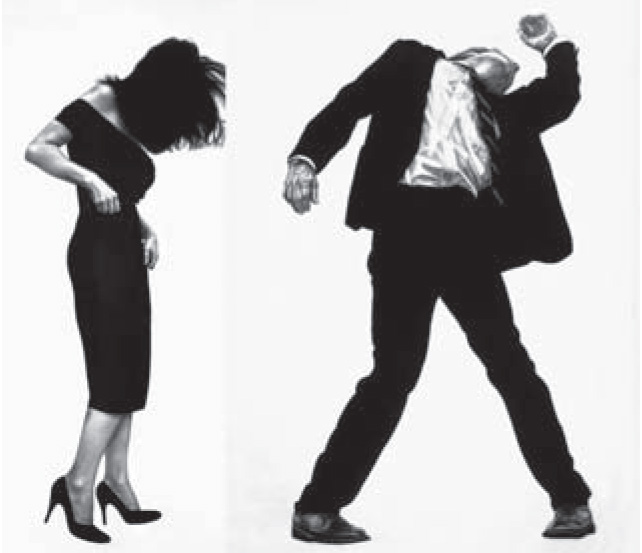

I say “happened to be” there, but actually I was there because a half hour hence, downstairs in the basement, I was going to be delivering a talk on Irwin, the subject of my first book, from 1982, called Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, which in fact had culminated with a depiction of the original rendition of this very piece. Many of those who would soon be in the audience were likewise milling about, taking in the approaching eveningtide, and presently I found myself conversing with one of them, a compact gentleman in a leather jacket, who turned out to be the eminent ’80s-generation artist Robert Longo, famous, for example, for his startlingly realistic depictions of snazzily dressed urban men and women, eerily arrested in mid-swoon.

Longo began to tell me a story about the first time he met Irwin, back in 1977, and it was getting to be a good story, so I interrupted him and asked whether he’d be willing to share it with everyone later, down at my presentation. And he said OK.

So, about an hour later, when I got to the part in my talk where I described how across the ’60s and into the early ’70s Irwin had systematically dismantled all the usual requirements of the art act (image, line, focus, signature, object) till he got to the point where he abandoned his studio altogether and simply announced that he would go anywhere, anytime in...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in