In the “Oxen of the Sun” chapter of Ulysses, James Joyce presents sound-bite snippets of voices that move chronologically from Anglo-Saxon straight through to contemporary speech. I had a similar sensation of working through layers of literary history while reading Vladimir Sorokin’s Ice trilogy, three interlinked novels published together for the first time this year by New York Review Books and fluidly translated by Jamey Gambrell. The eponymous narrator of Bro, the first novel in the series,1 enjoys an idyllic childhood of privilege in the twilight of czarist Russia, as the son of a wealthy merchant. This life, beautifully evoked by Sorokin in full Nabokovian mode, is quickly obliterated, along with the narrator’s immediate family, by the Bolshevik revolution. Orphaned and traumatized, Sasha Snegirev is drifting through university in the new Soviet world when a classmate recruits him for a scientific expedition to Siberia under the charismatic Leonid Kulik (the scientist who led the real-life trek this story draws on). Its mission: to locate the remains of the meteorite whose explosion in Earth’s atmosphere is presumed to have caused the great fireball that appeared over the Tunguska region in 1908, flattening more than eight hundred square miles of forest.

Known in UFO circles as the “Russian Roswell,” the Tunguska event has long been a magnet for esoteric speculation, in large part because no fragments of the giant meteor, nor even its impact crater, have ever been found. (In his 1946 story “The Explosion,” Alexander Kazantsev famously styled the Tunguska event as the massive nuclear explosion of an extraterrestrial spaceship.)2 In what will prove to be no coincidence, our hero was born on the day of this catastrophic historic event. He’s been haunted throughout his young life by a vision of a “Light” at the top of a great mountain, and finds his only deep pleasure in astronomy classes where he tells us, in the distinctive style of typographic emphasis Sorokin favors, “I simply hung among the stars.”

Selected mainly because of the apparent good omen of his birth, the merchant’s son embarks on a fateful journey that initially offers further echoes of Nabokov (the lepidopterological expedition to Central Asia in The Gift, a work dismissed by a character in the third novel of Sorokin’s series as boring). But in Siberia, Nabokov and modernity get kicked off the wagon for good as the story takes a completely different turn to—what? That is the great aesthetic and moral question of these novels.

*

Here’s what happens: Approaching the impact zone, the young man feels strange inner stirrings. His childhood dream of the Light recurs, he quits talking and eating; finally, he abandons the group in search of what he calls the huge and intimate, the mysterious energy that is calling to him. Striking out alone across the empty taiga, he plunges into a bog and swims wildly until he reaches the tip of the meteorite. Against all reason, it’s not made of stone or iron but Ice, “an ideal Cosmic substance generated by the Primordial Light” now safely preserved in the Siberian permafrost. In his excitement, he slips and falls, hitting his chest hard and thereby unlocking a mystic connection with the Ice, which gives him his true name, Bro.

Singing the “Music of Eternal Harmony,” the Ice reveals to Bro the secret cosmogony of the universe. In the beginning, outside space and time, there was only the Primordial Light. This Light consisted of exactly twenty-three thousand rays, one of which was Bro. Their function was to create worlds, and this they did, stars and planets beyond number, all radiating Eternal Harmony. Then they made Earth, a creation that became their “great mistake” because they made it out of water. This unstable medium mirrored the rays back to them with the catastrophic result that they got trapped in their own reflections and incarnated as mortal creatures on Earth—first as simple amoebas, then evolving over billions of years into humans, soulless carnivores who engage in the mindless, repetitive acts of killing and birthing, all the while exploiting the natural world around them.

The 23,000 rays of Light, the Ice voice goes on, have been trapped in these sordid bodies, their hearts asleep like those of humans, until that pivotal moment in 1908 when the “huge piece of Heavenly Ice,” encased in a protective hard shell of cosmic dust, dropped to Earth on a mission: to recover the rays so that they, in turn, might save the “perishing Universe.” Bro’s mission is to find and awaken the other 22,999 rays hidden in their fleshly prisons. Once these blond-haired, blue-eyed children of the Light are able to gather in one place and join hands, Earth will dissolve. The liberated rays will regain their identity in the essential world and will go on to create a “New Universe—Sublime and Eternal.”

Presented in the same breathless, breakneck prose as the rest of the story, this information comes across more plausibly (if that’s the right word) than a summary might indicate. Still, as a reader who had settled comfortably into adventure-on-the-tundra reading mode, I found the sudden left turn into Gnostic fantasy startling. My reaction put me in mind of the shock I felt in my first encounter, circa 1980, with the work of the dissident émigré Russian artists Komar and Melemid: a lovingly socialist realist rendering of a World War II partisan in greatcoat and rifle standing heroically vigilant in the night forest. (At the partisan’s feet, unnoticed by him, a tiny dinosaur cavorts.) Resetting my reading dials for that distinctive K & M brand of subversive irony, I readied myself for postmodern satire and a parable of the authoritarian political system that ruled Russia for seventy years, so often compared (by Eric Voegelin and others) to a Gnostic elite claiming the special knowledge needed to bring about apocalyptic changes in humanity’s condition.

Once again, my expectations were confounded. This is no clever allegory of communist idealism gone wrong, or even a parody of Aryan Übermenschen, though the genetic exclusivity of the children of the Light is a tipoff that something’s not quite kosher about them. Sorokin is not being ironic about Bro’s membership in the children of the Light; he is, to channel Bro’s voice, dead serious. Not that 23,000 cosmic rays incarnated as humans exist anywhere outside his own imagination, of course, but rather that experiential mysticism is a real phenomenon whose personal, social, and spiritual implications deserve to be examined and critiqued.

Though Sorokin writes within a literary culture of postmodernist irony (and his works show the distinctive high lit/pop sci-fi mix that usually earns this label), this trilogy draws its deepest inspiration from the symbolist/apocalyptic tradition of Andrei Bely and other Russian writers of a century earlier.3 (Let it be noted that these days, presenting transcendental experience as real is a far more subversive and unsettling proposition than any of the conveniently shifting positions taken inside the boundaries of late-twentieth-century postmodernism.)

It’s more fruitful, then, to look directly at the ways Sorokin presents Gnosticism as a worldview here. Gnostic thinking has never been monolithic, but as a tradition it has long carried the all-purpose label “world-hating.” In most Gnostic systems, the more physical something is, the less “being” or ultimate reality it possesses; perfection is to be found only in the transcendent realm, from which the soul descends to incarnate on Earth, and to which it ascends when its earthly sentence is over. Some Gnostic adepts over the ages, including Bro and his brethren, have forsworn sex and meat-eating on the principle that any substance generated by sexual intercourse is more deeply tainted by the inherent corruptibility of matter than plant life is.

For the early Gnostics of late antiquity (who often called themselves “children of the Light”), the material world was an accidental creation not of God, but of a clumsy intermediary. The Apocryphon of John 4and other Gnostic texts of the third and fourth centuries CE, tell the story, in various complicated versions, of the first human created as a reflection of God on the watery matter of this world. Then the ignorant lower god Yaldebaoth (a stand-in for Jehovah), offspring of Sophia (Wisdom), who is herself the daughter of God, tries to go one better by forming a fleshly man out of this divine reflection. The demiurge’s creation doesn’t come to life, however, until Sophia breathes her own essence into it. Thus humans, paradoxically, have more of the divine in them than does the false creator who made them, inspiring his envy and leading to endless repercussions—repercussions that play out in the Ice trilogy as well as in the ancient texts.

As visitors from the world of Light accidentally trapped in the watery prison of matter, Bro and his cohort of blond-haired, blue-eyed, celibate vegetarians are clearly modeled on the teachings of these early sects. Sorokin’s Gnostic cosmogony, however, offers some interesting new features. Most notably, he presents his children of the Light not as human believers but as the incompetent demiurges themselves, sucked down to Earth by the narcissistic pull of their reflected images and imprisoned in human bodies. In keeping with the older tradition, these clumsy creators ultimately reveal themselves to be false, unreliable, and faithless, both to the higher God they serve and to the spirit of the Light they embody. In the end it will fall to the human “meat machines” they despise to take up the search for the true God.

To return to the story: Handed his marching orders by the Ice, Bro sets off at once to locate his sisters and brothers around the world and reawaken their hearts to the Light. When Bro initiates his first sister, a runaway peasant, with a blow of the Ice to the chest, they have an ecstatic nonsexual experience of transcendental union, rapture that quickly converts into the burning desire to find all the others. Devising an “Ice hammer” with a chunk of the meteorite lashed to a wooden handle with straps of animal skin, they locate their brethren in the unlikeliest stations of life, from a bandit captain to the head of the Cheka for the Far East. Deeply and painfully aware of the cruelty of humans toward each other, the children of the Light soon reveal an equal ruthlessness in achieving their goal. When he kills his first man (in self-defense, fighting bandits), Bro realizes, in Sorokin’s inimitable typography, that “we would NEVER be able to REACH AN AGREEMENT with people.” Instead, he decides, they must begin “a long, persistent war against humankind.”

This marks the first of many progressively darker moral turning points for Bro and his fellows. As they move out into the world with their Ice hammers, power, not love, becomes the brethren’s first priority. “In order to sift through the human race, searching for the golden grain of our Brotherhood,” Bro declares, “we had to control this race.” In 1920s Russia, this means aligning 100 percent with the state: “We couldn’t allow ourselves to become underground members of a secret order, hiding in the dark corners under the hierarchical ladder of power. That road led only to the torture chambers of the OGPU [Cheka] and the Stalinist camps. We had to clamber up this ladder and stand solidly on it.” In Sorokin’s fictional universe, the head of the Cheka, once awakened to his cosmic identity, does not throw over his blood-soaked duties to become an ascetic meditating in the forest. Rather, the newly christened Ig, né Comrade Deribas, continues on his merry path of torture and execution and so is able to provide invaluable protection to his cosmic Brotherhood.

The reuniting of the children of the Light will take the next eighty years and all three novels to accomplish, an epic quest whose devolution from idealism to fanaticism to base and cynical brutality—as the alphabet soup of power they parasitically attach themselves to morphs from OGPU to NKVD to KGB—makes for riveting reading. Ice, the second novel, picks up the story in the 1990s, with flashbacks to the postwar Soviet era. Over the decades, the tone of the great mission has altered from mildly compromised exaltation, with only the odd chauffeur or army colonel executed to preserve secrecy, to ugly expedience. The brothers and sisters wield their Ice hammers brutally and carelessly in a ritual that’s become cruel, unexplained, and frequently lethal. Still boasting of their love “as large as the sky, and as sublime as the Primordial Light,” they now so despise the “meat machines” or “empties” (as they call humans) that potential recruits are often simply killed if they don’t prove to be part of the chosen 23,000. In their quest for the Great Transformation, the new female seer Khram admits, they “were merciless to the living dead.”

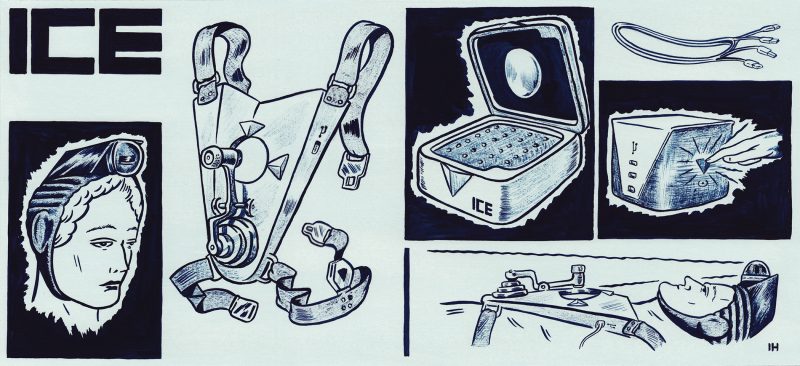

After the fall of communism, the children of the Light all too successfully transition into the Wild West era of post-Soviet capitalism. Under Boris Yeltsin, they are able to create “mighty financial structures” within the new oligarchy within the new oligarchy, operating under the same conditions of corrupted absolute power as previous regimes. They drive the same fancy cars as the thugs, pimps, and thieves who deliver the dwindling stores of their precious Ice. The Ice is mined by convict labor in the Tunguska region, where imprisoned scientists also craft Ice hammers for mass distribution in a home kit called the “ICE Health Improvement System.” Touting the benefits of being struck on the chest with the Ice hammer, the kit is a covert form of recruitment that becomes a worldwide commercial success. Sorokin’s chameleon style has shifted to on-screen webspeak replete with bolded words; the novel ends with their website’s array of testimonials from customers around the world (perfectly mimicking the random cluelessness of the average Amazon product-review section), and the discovery of a mentally disabled boy who is the long-sought male seer to be paired with Khram after Bro’s death.

The final installment, 23,000, ends in 2005, almost a century after the Tunguska meteorite event. Peppered with shifts in point of view, the story mainly contrasts the exalted rhetoric of Khram with the matter-of-fact perspective of a Russian “empty” named Olga. (The humans, who make their first appearance in this last novel, are rendered not in the exclamatory “I” voice of the rays, but in the more distanced third person.) By now, the children of the Light have incorporated into a multinational conglomerate, and Olga finds herself enslaved, along with a few hundred other blond, blue-eyed failed recruits, in an outsourced Chinese factory, grotesquely consecrated to skinning the dead dogs whose hides are used to strap the handles of the Ice hammers.

Meanwhile, the day of reckoning has come. (If you do not want to know what happens next, reader, stop right here.) The last rays are located just as the final shipment of Ice arrives from Siberia. The entire group gathers on an island off China for their long-awaited ascension. As “part-hammered” humans who begin to share the rays’ “longing for the Light,” Olga and her Swedish coworker Bjorn are recruited to hold “awakened” ray babies in the Prime Circle where the rays stand naked. The Twenty-Three Words are recited, Earth shudders, and Olga and Bjorn open their eyes to discover the human bodies of all 23,000 lying dead around them, faces frozen in grimaces of suffering and bewilderment. The ascension, if that is what happened, was apparently not a pleasant one, and Earth itself remains intact.

This denouement irresistibly recalls the fate of real-life contemporary Gnostic cults, such as Heaven’s Gate and the Order of the Solar Temple, whose apocalyptic millennial quest to reach the “Next Level” moved many of its followers to hasten the process with mass suicide. Sorokin, however, has asked us to accept the 23,000 rays not as a deranged human cult, but as exactly who they say they are—nonhuman energies from somewhere other than Earth. So what went wrong for these incarnated cosmic rays?

They “crashed against” what they created, Bjorn tells Olga. As in the ancient Gnostic stories, the 23,000 rays, aware only of their own cosmic identity, labor under the delusion that they alone have created the universe. Beyond the reach of these clumsy cosmic demiurges, who further compromised themselves with vile deeds while incarnated, lies a true, or higher, transcendence. It is known by the word that is never uttered until the last page of the third novel, and only, significantly, by human “empties.” Humans alone have the ability to apprehend their true creator, God, because humans possess a greater share of divinity than their immediate overlords.

The unhappy demise of the children of the Light was done “for us,” Bjorn cries, “and this was all done by God!” His declaration triggers the following remarkable exchange:

“By God?” Olga asked cautiously.

“By God,” he declared.

“By God,” Olga answered.

“By God!” he said with certainty.

“By God,” Olga exhaled, shaking.

“By God!” he said in a loud voice.

“By God!” Olga gave a nod.

“By God!” he said even louder.

“By God!” Olga nodded again.

“By God!” he shouted out.

“By God,” she whispered.

Both agree their next step must be to talk to God themselves. To find out how to do this, they must return to the “World of People” and ask other humans. And off they go, “their bare feet stepping across the sun-warmed marble.”

Sorokin’s parting message—that the task of the new Adam and Eve, expelled from the dreadful underbelly of the children’s Paradise, is to go forth in the world and discover the ways of accessing the transcendence known as God—is unlikely to sit well with a secular humanist intelligentsia such as our own. Contemporary works of serious literature with mystical import are few and far between in the West, though Gnostic fantasy abounds in twentieth-century American popular culture, including Thomas Pynchon’s exuberant 1961 conspiratorial historical fantasy, V., and Theodore Roszak’s Flicker (1991), an ingenious Gothic romance about a two-thousand-year-old Gnostic cult responsible, among other things, for German expressionist film. Alexander Key’s Escape to Witch Mountain (1968), a tale of a brother and sister from another galaxy cast away on Earth and searching for the others of their kind, is better known through its film adaptations.5 The 1995 movie version reframes the story more explicitly as a Gnostic metaphor: groups of brother-sister twins exiled and scattered in our world reunite and happily ascend two by two back to their true world via a column of purple iridescence known as the Light.

Closer to Sorokin’s home base, the children of the Light share a few resonances with the popular Night Watch series (1998–2005) by Russian science-fiction writer Sergei Lukyanenko (adapted into global hit films by the director Timur Bekmambetov), about a supernatural horde divided into two groups, Light Ones and Dark Ones, locked in eternal combat on Earth. The rays’ demiurgic fashioning of a watery planet also finds some echoes in Polish writer Stanislaw Lem’s 1962 novel Solaris (made into films by Andrei Tarkovski and Steven Soderbergh), about an oceanic world consciousness that tunes into the deep obsessions of the scientists come to study it and reflects them back in the form of human simulacra.

The story Sorokin himself singles out, however, is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s strange 1920s fantasia “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz.” With its uneasy worship/critique of the condition of limitless wealth, this capitalist fable of a man who owns a mountain made of a gigantic diamond could have served equally well as a popular classroom text in Soviet times or as a cautionary tale for the new Russia. Reading this story of a “stingy, powerful man” whose fantastic treasure turns him into a monster, Olga reflects on her own fate serving the Ice elite: “Diamonds look like ice… But diamonds don’t melt… the ice mountain. And we live under it…”

It’s much easier, though—especially because of the dense and dark Russian sociopolitical matrix the Ice trilogy is embedded in—to back off from cosmic considerations entirely and read these novels simply as social metaphors. Sorokin himself has called them a “metaphor more than anything else,” a “discussion of the twentieth century… a kind of monument to it.” His two other novels available in English also feature dubious collectives as their main characters: an elite force of despicable thugs who enforce the will of a new absolute czar in a futuristic Russia in Day of the Oprichnik (2006) and a marginally more benign multivoiced entity in his first novel, The Queue (1985). In his afterword to a new edition of The Queue, Sorokin proposes that the “collective body” formed by the endless lines of people waiting for goods and services in the old Soviet society represents a “new type of object or metaphorical subject.” The queue itself, he suggests playfully, neatly replaced the services of the Russian Orthodox Church (during which the congregation traditionally remains standing), dispensing cabbage and American jeans instead of the Eucharist.

The Queue and Day of the Oprichnik are indeed metaphors, parables, fables of a Russian society separated by thirty years but unchanged in certain grim fundamentals.6 Both works, however, differ strikingly in tone from the Ice trilogy, and from each other. In the over-the-top, heavily satiric Day of the Oprichnik, which Sorokin says he composed in a single month, “like an uninterrupted stream of bile” after five years of writing the Ice trilogy—and as part of a conscious decision to become more politicized in his writing—the elite cadre of Day of the Oprichnik experiences a profane sacramental ecstasy as a consequence of group bonding even as it extols its own purity in the wake of unspeakable crimes. Where Bro and his brethren are entirely chaste (“No earthly love that I had ever experienced before could possibly be compared with this feeling,” he cries. “I ceased to be a two-legged grain of sand. I became we! And this was OUR HAPPINESS!”), the oprichniki indulge in a ritual sexual orgy of male bonding. Here the (relatively) innocent image of the “many-headed caterpillar” of collectivity invoked in The Queue gets played out in the form of a sodomizing “caterpillar” copulating and climaxing in its secret bath. It is a damning emblem of the consequences of absolutism in Russian society past, present, and future.

Are the 23,000 rays of Light, then, simply a metaphorical subject—yet another incarnation of the Russian caterpillar—or are they the real thing? (Those italics are contagious.) Is Sorokin passing judgment on the perils of human absolutism, or (more fancifully) on the failings of the Gnostic archons, the intermediate gods who created our world? Answer: Both. The children of the Light are metaphorical subjects and “real” at the same time, but the deeper subtext is the transcendental one. In the Ice trilogy, Sorokin is using the outer manifestations of Russian society to critique inner and transpersonal experience, not the other way around. In 2008 he told an interviewer:

I believe that humanity is not yet perfect, but that it will be perfected, that contemporary humans are thus far imperfect beings, that we still do not know ourselves or our potential, that we have not understood that we are cosmic beings. We are created by a higher intelligence, and we have cosmic goals, not just comfort and reproduction. We are not “meat machines.”

But this astonishing (to some) declaration only raises more questions. Does evil arise automatically from the energies of the collective, regardless of whether it’s human or cosmic? For that matter, which part of the incarnated rays, their human bodies or their cosmic nature, brings evil to the table? Khram is scathing on the subject of humanity’s capacity for evil: “There could be no brotherhood between meat machines,” she declares. “Each meat machine wanted happiness for his own body above all… And they constantly killed each other to achieve the body’s happiness.” Does this mean that the children’s originally pure cosmic essence has been corrupted by their human, all-too-human, incarnated nature? The humans in the Ice trilogy believe the opposite—that the cruelty of the Brotherhood stems precisely from their nonhuman nature.

Sorokin himself splits the difference, and this is what I think his “metaphor” amounts to: The children of the Light are us. We humans, all of us, are part meat machine, part cosmic ray. The quest that Olga and Bjorn embark on in the World of People is no final ironic twist, initiating another spiral into deluded religious fanaticism. Nor is it an adjuration to turn away from the evils of fanaticism for the joy and comfort of secular humanism. Olga and Bjorn have a serious task before them that is anything but postmodern. It is to understand their natures as “cosmic beings,” and that means finding God.

Where do we find God? In the World of People, as Bjorn says, but most certainly not in any of the usual places, including the Russian Orthodox Church. A priest who has sampled the ICE “Health Improvement” kit screeches about it as an implement of the devil. Though he is weirdly right about the children of the Light, he hates them for the wrong reason, namely, because they don’t follow the Church’s precepts. But if traditional religious institutions are useless, must Olga and Bjorn, following Bro’s example, form a new ruthless elite in service to their cosmic nature? Is the Ice story merely starting all over again? Or can there be another way?

The trilogy reveals itself at the end as a manifesto against its own story’s premises, anti-Gnostic and anti-apocalyptic. The children of the Light, all of us, belong on corrupt, compromised Earth, because it makes up half our nature. We access the Light not by escaping but by being what we are. Knowing the world they are walking back into, we tremble for Olga and Bjorn—but the hope and energy they exude is unmistakable. Sorokin leaves them on the brink of a future that is wide open and, as yet, untainted.

And is this God they’re looking for, finally, another metaphorical subject, or is he/she/it the real thing? To answer this question in any way other than with our own knee-jerk humanist biases, Sorokin suggests, we must make the same journey ourselves.