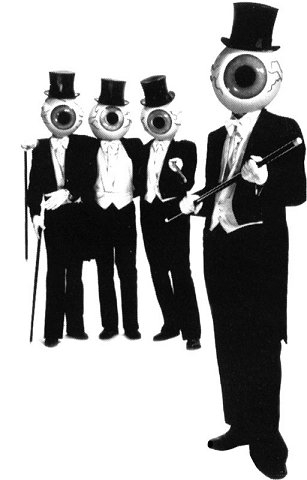

The Residents announced their presence on the subcultural landscape in 1972 with the release of Santa Dog, a four-song double single that was simultaneously catchy, abrasive, and confounding. Over the course of the next forty-six years, the legendarily anonymous, eyeball-headed San Francisco-based avant-pop performance quartet has released roughly fifty-musical albums, each radically different from all the others, and each in some way an experiment. Imbued with an aesthetic and mindset that seems to be based in some other dimension, their videos have been added to the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection. Their wildly theatrical performances fit Richard Wagner’s definition of a Gesamtkunstwerk with their blend of music, poetry, dance, acting, costuming, and visual art. They created award-winning animated CD-ROMs when CD-ROM was poised to be the next generation home entertainment platform. They’ve posted several innovative, mind-bending series online, including a serial radio drama. There have been several international exhibitions of their painting and elaborate costume designs. They’ve scored ballets. They made, well, at least a good chunk of the classic cult film Vileness Fats, And are presently at work on a new feature, Double Trouble. They’re also currently completing their next studio album, Intruders, and overseeing the development of a stage adaptation of their 1989 album God in Three Persons.

For all their forays into nearly every imaginable art form, it wasn’t until 2013 that The Residents published their first novel, Bad Day on the Midway. Bad Day was in essence a novelization of the interactive 1995 CD-ROM of the same name, a complex murder mystery involving, among others, a serial killer, a young innocent named Timmy, sideshow freaks, and a red-headed rat carrying the plague, all set at a seedy roadside carnival.

“Bad Day was a fully developed project that was floundering in oblivion,” says The Cryptic Corporation’s Homer Flynn, longtime manager and spokesperson for the fiercely reclusive band. “Nobody could play [CD-ROMs] anymore, but The Residents felt more could be done with it to keep it alive, so they turned it into an old-fashioned novel.”

Now, five years later, Feral House/Process Media has just released The Residents’ first wholly original novel, Brickeaters. The Bad Day novel was not only based on pre-existing material, but also originally conceived as an interactive eBook that would employ the rich computer animation of the CD-ROM. Brickeaters, on the other hand, was from the beginning conceived as a physical book, with a cover and pages and a story. It seemed an odd step into the archaic for a band long associated with cutting-edge technology.

“The Residents are voracious readers,” Flynn...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in