I. The Back Paddock

The grassed back half of the school where we played when I was a child was called the Back Paddock, and sometimes we found things there. The Back Paddock bordered a quiet suburban street on one side, and on the other was the high barbed wire of one of the state’s largest juvenile-detention facilities. Teenagers broke into the Back Paddock at night. It must have been perfect in the privacy of the dark. In the mornings before class began we would find beer cans and broken bottles of rum, KitKat wrappers, syringes, and wet condoms filled with semen. These, and the strange things that sometimes happened, like the teenage boy who once bicycled naked past the window of my grade-two classroom, were frequently attributed to the juvenile-detention center next door. There was, in the end, no real way of knowing where the bicyclists and beer cans and condoms came from. Besides, it was never those things that rattled me. What rattled me was the clothing.

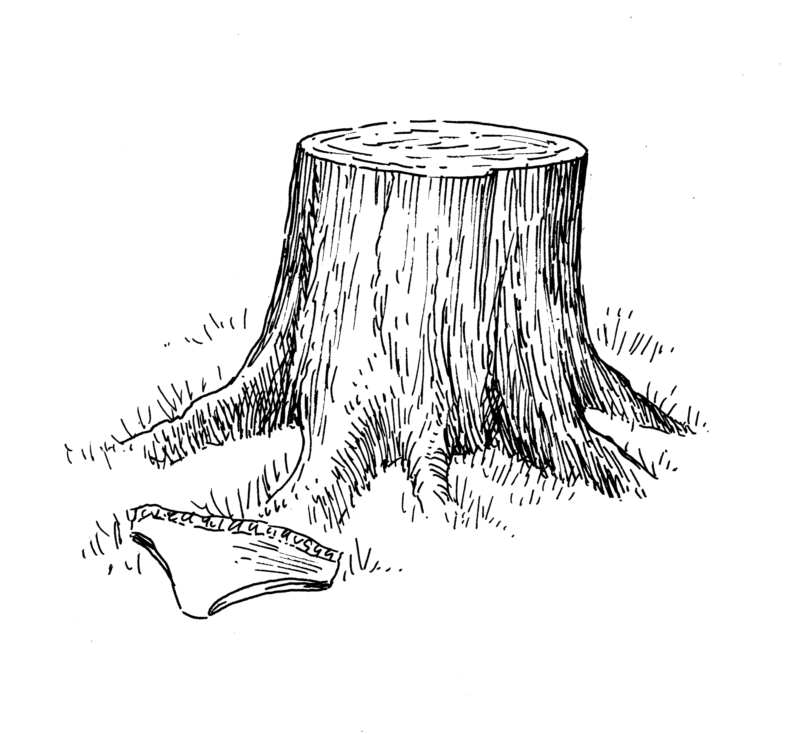

When I was six, I found a pair of pink underpants by a tree stump. The next year, I found a pair of adult men’s track pants. I was eight when the clothing began migrating from the Back Paddock proper to the concrete playground outside my classroom doors. One winter morning I arrived early to school and found an entire outfit outside the grade-four classrooms. There was a blouse, a jumper, jeans, a bra, socks, and underwear. I remember that the underwear was dirty and had been left crotch-up on top of the pile. The pile frightened me for reasons I couldn’t articulate, and I backed away from it to the wet-weather shed, where I waited for the other children to arrive.

I asked our teacher later that day about the woman those clothes must have belonged to, and whether she was naked now. I was worried because it had been so cold the night before. Why were the woman’s clothes there, I asked, and not on her body? And where was that body now?

II. Faces in the Rock

There is a scene in Picnic at Hanging Rock in which Mademoiselle de Poitiers, the French tutor at Appleyard College for Young Ladies, is overcome with horror. In Peter Weir’s 1975 film version, she looks around and shakes her head, but in Joan Lindsay’s original 1967 novel, the tutor’s thoughts are explicit. She stands by the edge of a creek, looking up at the rock overhead, and wonders “how anything so beautiful could be the instrument of evil.”

That nonspecific evil is at the center of both the novel and the film. Both follow a group of schoolgirls...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in