CENTRAL QUESTION:

Can the weird world be made manifest through language?

John Olson’s poetry is a linguistic burlesque show. Every aspect of the English language gets done up in feathers and spangles to shimmy and titillate, and you can almost hear the bawdy trombone accenting John Olson’s poststructuralist puns, his sonic shenanigans. He announces as much in the first line of this excellent compendium: “The exhilaration of poetry is in its gall, its brassy irrelevance and gunpowder vowels, its pulleys and popcorn and delirious birds.”

This exhilaration is far from what critic Ron Silliman calls the “School of Quietude.” With every word and part of speech, nothing is commonplace and everything is loud and out of school. Olson makes a poem by recording his superhuman sensory experiences as accurately as possible. Here is “Xylophone”: “a hive of bells / pollinating rhythm / and beryllium / beaten into rain.” Can you hear it?

To call this kind of work clever would be a massive understatement. Olson employs delicate shades of irony, from light self-consciousness to savage parody. His language is constantly in pursuit of the ineffable, though so playfully, and so relentlessly, that reading his work for any length of time is likely to scramble your brains. He’s a master of the late-capitalist lyric—a surplus of music and meaning is a fact of life. The sanest thing to do in such a world is to laugh to keep from crying. But this isn’t snickering over a thin veneer of sarcasm— it’s a Marx Brothers belly laugh.

“For sale the rusted artery of a galactic bulldozer replete with insignia, crowbar, and dreary motel curtains.”

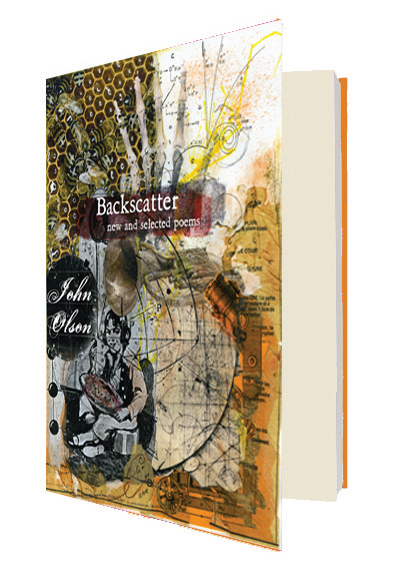

Clearly, Olson’s far too playful a poet to ever get his critical due in polite society. Nonetheless, he is a true catawampus heir to the American lyric tradition of Dickinson, Poe, Stevens, and Ashbery (by way of Robert Desnos and Raymond Roussel, among many gleeful others). He’s also crept up on this world, having slipped six books under the radar in the past decade, most of which escaped the notice of anyone outside of the select coterie who fawn over books by his previous publisher, Black Square Editions. (Hello, dank apartments!)

In those books, readers saw how Olson could uniquely construct a reading consciousness from scratch. Though he is clearly well versed in literary theory of the French persuasion, he doesn’t take any of the gleaned insights for granted. He earns each frisson poem by poem, often taking an everyday moment or object to build upon.

In the poem “The Mystery of Grocery Carts,” for example, he writes, “I look to the left and notice beads of water dripping from the wires of the...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in