Central question:

Who is Pippa Lee?

Rebecca Miller is a writer first—first she writes the book, then she makes the movie. As a fiction-writer/director, she’s no moonlighter. She’s taken multiple turns in the desk and director’s chairs, and her process calls to mind the way Graham Greene approached his film treatment for The Third Man: “To me it is almost impossible to write a film play without first writing a story. Even a film depends on more than plot, on a certain measure of characterization, on mood and atmosphere; and these seem to me almost impossible to capture for the first time in the dull shorthand of a script.” So Greene wrote a novella. Done with that, he wrote the screenplay. Miller has done Greene one better: she’s directing the movie of her screenplay adapted from her debut novel.

Doting mother of two, devoted spouse, Pippa Lee has a complex past. She suffers from an “excess of empathy. Sometimes, she found the mystery of other people almost unbearable to contemplate: rooms within rooms inside each of them, an endless labyrinth of contradictory qualities, memories, desires, mirroring one another like an Escher drawing, baffling as a conundrum. Kinder to perceive people as they wished to be seen. After all, that’s what Pippa wanted for herself: to be accepted as she seemed.” At fifty, Pippa has moved to a Connecticut retirement community, and she’s not adjusting. Her early entry into the sagging, slowing ranks of old folks—having left behind, without a backward glance, the social and kinetic extremes of Manhattan privilege—is necessitated by the bad turn in her husband’s health. Herb Lee, nearing eighty, is a publishing scion, “heroic owner of one of the last independent publishing houses in the country.” Herb has edited most of the literary lions, Sam Shapiro among them, “probably the finest fiction writer in the country.” Sam and Herb have a kind of Thomas Wolfe–Maxwell Perkins co-dependence. “Sam had been so loyal to Herb, in fact, that people began to wonder if the great Shapiro needed his editor a little too badly.” This becomes the emotional crux: all of the characters need one another more than is healthy—all of the characters, it would seem, except Pippa.

Miller constructs her novel like a screenplay—in three acts. Part one: Pippa in the present, before her hushed breakdown and backward spiral. Part two: Pippa in the past, the chronicle of her coming-of-age. Here the point of view shifts, from the third-person position of psychological remove in part one, suggesting the emotional distance of Pippa’s adulthood, to the first-person egocentricism of Pippa’s youth. This shift, and her command of language, proves Miller’s flair for the finer points of novel writing, but it also—here and elsewhere—puts on display her tendencies as a director, the way moving pictures and their makers play loose with point of view.

Part three picks up where part one left off—back in the present as it falls entirely apart. There are surprises, but they’re of character, not plot, and in the end, just as John Updike has so often given voice to the second acts in men’s lives, Miller beautifully renders an American woman’s grab and grab again at happiness. Given this day and age—of multimedia and “musical hearts,” to borrow Miller’s phrase—it makes perfect sense that the second life offered by the film version is in the immanent offing, as the first life, which is the novel, takes off.

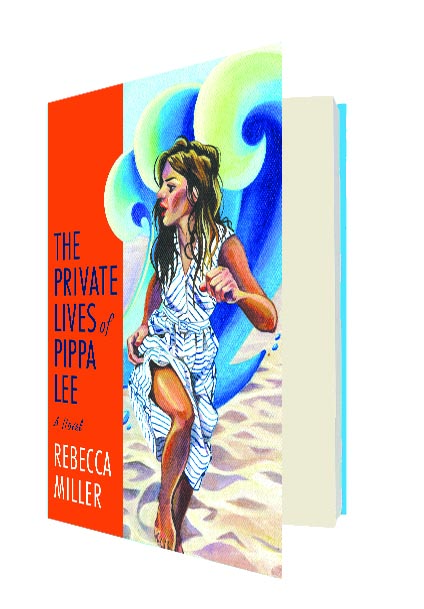

Format: 256 pp., hardcover; Size: 5 1⁄2” x 8 1⁄4“; Price: $22.00; Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Editor: Jonathan Galassi; Print run: 30,000; Book design: Charlotte Strick; Typeface: New Caledonia; Author is married to: Daniel Day-Lewis; Author is daughter of: Arthur Miller; Point in the writing when the author was certain she would direct the film adaptation: second draft, second year; Representative sentence: “Lucy admired the symmetry of the book, the careful pacing, the slow but steady drip feed of information—not too much, not too little; she called it a ‘mystery of character.’”