On the perfect spring morning of May 21, 1933, a gaggle of well-wishers and reporters gathered at Stag Lane Aerodrome, just north of London, to see a pilot off on an epic flight. In the excitement of his departure, he headed down the runway in the wrong direction, with the wind rather than into it. The crowd watched his tiny biplane lurch across the grass as it struggled to gain enough speed for takeoff, its wings flexing as if trying to lift off like a bird. Only at the very last moment did it finally claw its way into the air. This inauspicious start must have left those present wondering if they would ever see Maurice Wilson and his plane, Ever Wrest, again.

Two years later, British climbers approaching the foot of Mount Everest’s North Col found the body of a man dressed in a mauve pullover and gray flannel trousers sitting by the tattered remains of his tent. He had been deep-frozen in the process of removing his boots. They guessed immediately that this was Maurice Wilson, reports of whose death on the mountain had been circulating since the previous year. After recovering his diary and some other effects from his pockets, the climbers buried his corpse in a crevasse. Eric Shipton, one of those present, wrote: “Where we tipped it in, it completely disappeared. There was no hole where it fell. Just plain white snow.”

In the years since, Everest has become a vast mortuary where climbers step over their fallen predecessors on their way to the summit, but for these men the discovery of the body of a fellow countryman in this remote and hostile place was still a shock, and cast a pall over the group that evening as they huddled in their tents, taking turns reading from his diary.

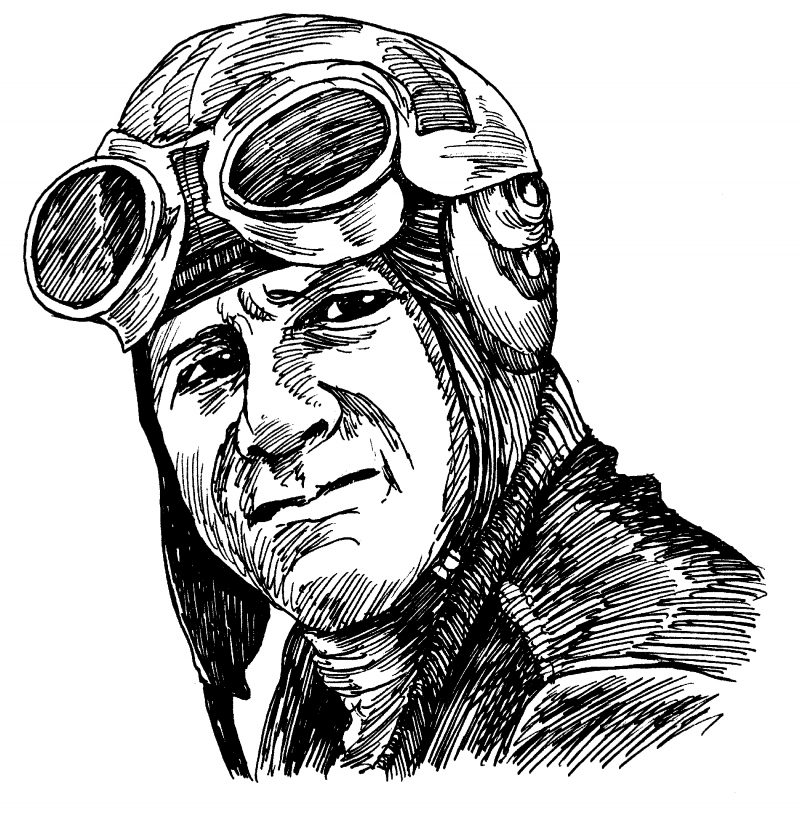

Wilson’s was not the only, nor the most famous, corpse on Everest. The British expeditions of the early 1920s had been dogged by ill fortune. In 1922, seven Sherpas had been swept away by an avalanche, and in 1924 Andrew “Sandy” Irvine and George Mallory had disappeared during their bid for the summit. But where Mallory has become the object of an almost cultlike following, Wilson has been relegated to a humorous footnote in the history of Everest, forever known as “the Mad Yorkshireman.” Mallory was an elegant figure, much admired by the Bloomsbury set for his good looks, easy charm, and breeding; Wilson was a tall, blunt man with doughy features, from a stolid, respectable Yorkshire family that made its living managing textile mills in Bradford. Where Mallory was a fine mountaineer with a laconic turn of phrase, Wilson attempted to...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in