The auditory capacities of teeth may be demonstrated through a simple test. First, find a quiet room to sit in. If you are wearing an analog watch, remove it from your wrist. Open your mouth wide and suspend the timepiece inside your mouth without actually touching your teeth. You will hear a quiet ticking. But close your teeth upon the watch, and you will hear a loud ticking.

This is because you are hearing with your teeth.

The Austro-Germanic Era of Dental Music

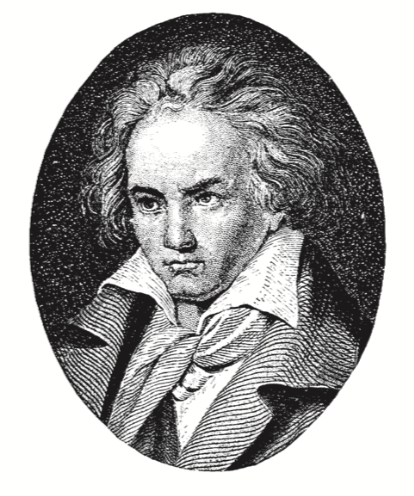

After the onset of hearing loss in 1798, Ludwig van Beethoven listens to his compositions by jamming a wooden rod between his teeth and resting the opposite end on his piano’s soundboard. The concept is known as bone conduction: by passing vibrations through his mandible and into the cochlea, Beethoven circumvented his damaged middle ear and routed sound directly to the inner ear. His method may have been inspired by a 1770 volume by countryman professor Andrew Elias Büchner, author of An Easy and Very Practicable Method to Enable Deaf Persons to Hear. Büchner, in turn, credited the discovery to a deaf merchant in Wesel in 1749. After finding that a tobacco pipe held against a piano soundboard would transmit sound right into a smoker’s head, the merchant also tried capturing sound from the air by clenching a hearing-trumpet in his teeth. This worked poorly; what worked well, however, was biting down on a thin and resonant scrap of wood. Buchner also notes that “the deaf person may hear very well by holding, by the lower rim, a beer-glass to the upper-teeth.”

After the onset of hearing loss in 1798, Ludwig van Beethoven listens to his compositions by jamming a wooden rod between his teeth and resting the opposite end on his piano’s soundboard. The concept is known as bone conduction: by passing vibrations through his mandible and into the cochlea, Beethoven circumvented his damaged middle ear and routed sound directly to the inner ear. His method may have been inspired by a 1770 volume by countryman professor Andrew Elias Büchner, author of An Easy and Very Practicable Method to Enable Deaf Persons to Hear. Büchner, in turn, credited the discovery to a deaf merchant in Wesel in 1749. After finding that a tobacco pipe held against a piano soundboard would transmit sound right into a smoker’s head, the merchant also tried capturing sound from the air by clenching a hearing-trumpet in his teeth. This worked poorly; what worked well, however, was biting down on a thin and resonant scrap of wood. Buchner also notes that “the deaf person may hear very well by holding, by the lower rim, a beer-glass to the upper-teeth.”

The Auditory Teeth Explosion of 1879

Buchner’s work on bone conduction is revisited by Viennese physician Ádám Politzer in 1864, but little more comes of the idea. Anecdotal usage abounds, however, with one Philadelphia doctor reporting of a deaf patient who bites railroad tracks to hear approaching trains. A more practical approach emerges in the 1870s, when deaf Chicago resident R. S. Rhodes experiments with a vulcanized rubber fan held by a wooden handle and clenched in the user’s mouth. By 1879 mail-order sales take off for Rhodes Audiphones at $10 each (or $15 for a Double Audiphone “for Deaf Mutes, enabling them to hear their own voices”). The invention is lauded in the press with heartwarming scenes of entire classes of deaf children, fans clenched in their mouths, hearing music for the first time.

Wooden rivals immediately follow: the Bostwick Audiphone uses a wooden rod connected to a telephone-style diaphragm, while Fiske’s Dental Attachment for Telephones actually connects a bite-rod directly to a working phone receiver. For those seeking convenience, Graydon’s Dentaphone is a pocket-sized hinged...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in