Young Jean Lee’s straight black hair is decisively asymmetrical, cut from one ear to swoop around the back of her head before angling down, brushing the opposite shoulder like the tip of a raven’s wing.

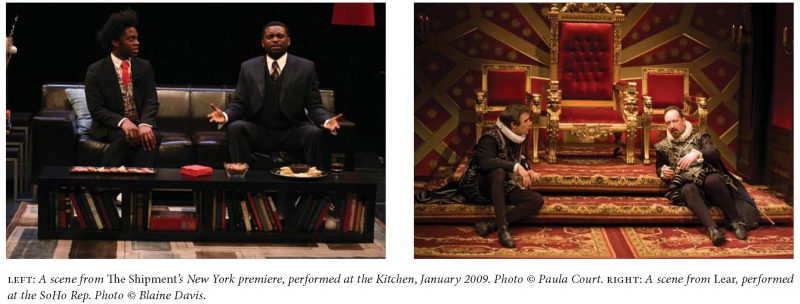

In Lear, Lee’s uncanny and profound 2010 adaptation of Shakespeare’s tragedy, a character, richly corseted in a jewel-hued gown, interrupts a conversation about funerals to declare, “Sometimes I feel sad at them, but other times I feel like: look at all the fashion!” There is a lot to look at, and as much to listen to, in Lee’s work—presumably only a keyhole glimpse into her wonderful, if terrifying, imagination. She once told the Nation how in an early work, Songs of the Dragons Flying to Heaven, she began with an image of several traditionally dressed Korean women “scuttling around the stage like crabs” to Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas Is You” and, in her words, “miming gruesome suicides.” It doesn’t really make any sense when you hear it, she said, but when you see it onstage, that song goes perfectly with the image. Lee’s theater presents a physical and psychic space where grief, insanity, and comedy run together without clear boundaries, alternately shocking and delighting. The songs go perfectly with the images.

In addition to exploring the seriously mixed bag of human feeling, Lee possesses an unrelenting interest in identity politics. It carries through much of her work, from the hilarious and harrowing Songs to the recent Untitled Feminist Show. This interest is perhaps best exemplified in Lee’s most well-known work, The Shipment, a witty examination of the many ways that African Americans were, are, and continue to be shaped by roles assigned to them by non–African Americans. The Shipment is political without being prescriptive, and with it Lee revitalized a form that has been overshadowed by nearly every other modern artistic medium.

Lee doesn’t strive to suppress her theatrical impulses. Instead, she figures out how to commit the most meaningful versions of them. She upholds the fantasy that a true artist possesses some preternatural creative capacity, as well as the conscious ability to make work that is politically lucid. But, like her hair, the power of Lee’s theater doesn’t lie strictly at either of these points but in the exhilarating arc between.

—Naomi Skwarna

I. PRISON GUARDS HAVING DRAMA

BELIEVER: I like this story that’s out there about you at 26, somewhat disaffected with academia and your dissertation, going to a therapist. The therapist asks you what you want to be, and you say “playwright.” What was it like – that period after you’d acknowledged that you wanted to do something different, and had to figure out how to do it?

YOUNG JEAN LEE: There was a long gap between that moment in the therapist’s office, the actual acceptance of it, and making the decision. It was really terrible. I think a lot of people in their twenties feel like they have no idea what they’re doing with their lives, and that was my experience. It was pretty typical, except that I had invested almost ten years of my life into pursuing – very single-mindedly – this goal of being a Shakespeare professor. The amount of work and passion I’d put into a goal that I ultimately didn’t even want was just so… when I think about it now, it’s crazy how hard I worked. I don’t know, it was such a terrible period. I remember talking to some of my friends on the phone – I was married at the time – and they were still in their twenties and struggling with relationships. They were like, You’re so lucky. You’re married—at least you’ve got that locked down. But it’s so much worse to not know what you’re going to do with your life than to be single! I remember it being such an unbelievably horrible time.

BLVR: How did you begin that shift from academia to theatre?

YJL: When I was in grad school at Berkeley, I joined a weekly playwrighting club that was started by Julia Cho, another playwright. I wrote a little one-act play and did a staged reading of it. I think I directed it? It’s very vague in my mind. But that’s one little step that I took towards the idea. Then after I passed my prospectus conference and I advanced to candidacy for my dissertation, I got married. My now ex-husband went to Yale Law School, so I moved to New Haven with him to work on my dissertation because I was done with all the university-related stuff. When I was there, I found out about a playwrighting group in a local newspaper—some listing. A bunch of local people had formed a playwrighting group in a little community theatre, and I just showed up. Most of them were amateur playwrights and they were all much older than I was, in their forties and fifties. They wrote incredibly, you know, just really, really straight plays. I was bringing in the weird writing that I was doing. My plays were so weird, and so it was just like—

BLVR: You were the young weirdo in the group?

YJL: Yeah, yeah! I was with these middle-aged people, and it’s like: plays about grieving spouses suffering through 9/11, or prison guards having drama together. And I was just bringing in these completely surreal, crazy things. And then they kicked me out.

BLVR: In a kind way? Like, they didn’t ask you back?

YJL: No, the leader of the group who I’d initially contacted, who had formed the group, sent me a letter saying that I was no longer wanted because my work was too weird.

BLVR: It’s a funny story to hear you tell it, but that must’ve been quite hurtful… or, I don’t know. Maybe you responded to it well. [Pause] Because you’re a badass.

YJL: I think I had a mix of emotions. The whole experience was really funny—it was absurd. It was an absurd situation. Me sitting in a tiny community theatre basement with all these middle-aged people writing 9/11 plays. It was just ridiculous, me bringing my writing in there. I think there was a part of me that felt the absurdity of it all along. It softened the blow, the fact that it was not something I took very seriously. Getting kicked out was sort of the perfect, absurd cherry on top of the sundae.

BLVR: It meant that immediately your work was having some kind of effect, you know? Enough that people didn’t want you around.

YJL: Right, right, right, right. And I think it was around the time they kicked me out that I had already made contact with Jeffry M. Jones at Yale University, who gave me a list of names of theatre people to look into…

BLVR: And that was shortly after you had said “playwright” to the therapist?

YJL: Oh no, it took years of therapy to get to the point where I could join the playwrighting club, or even try to write anything.

BLVR: The instinct when you hear yourself say something like that is to assume you’re crazy, to think that you’re being fanciful or something.

YJL: Especially if you’re in academia studying Shakespeare, and you’ve never written a play before, and you’re like I want to be a playwright! It’s kind of frowned upon in academia. Like, We study the Greats, and you want to be this… dabbler?!

BLVR: I’m sure all that studying was pretty important in relation to the work you did later.

YJL: Hugely important! I think I found out in therapy that the reason I was doing it was because I wanted to write plays. It wasn’t like I wanted to be a Shakespeare scholar, changed my mind, and then it came in handy for being a playwright. I wanted to be a playwright all along—I just couldn’t admit it to myself.

II. SO BANANAS

BLVR: It was around that time, I think, that Jeffrey M. Jones gave you that list of people to check out—Richard Foreman, The Wooster Group, Mac Wellman. Did you seek out other contemporary playwrights before that?

YJL: No. I don’t even think I’d heard of Richard Foreman or The Wooster Group. I hadn’t heard of any of those people! It was all news to me. I think the most contemporary playwright I’d read at that point was Beckett.

BLVR: And then you did an internship with Soho Rep. in New York. Were there any notable early experiences after you started working with them?

YJL: I was an arts administration intern at Soho Rep., but one day they sent me to see this show by a company called The National Theatre of the United States of America, a little experimental ensemble company. They’d made this show called Placebo Sunrise, and I just went bananas over it. I still think it’s the best thing I’ve ever seen in theatre, ever in my life. It was amazing. So I asked them if I could get involved and I ended up running the sound and light board for them.

BLVR: What was the show like?

YJL: They’d rebuilt this small space on 42nd Street into a posh little theatre with its own little stage. You’re looking at these two characters on this teeny-tiny stage, thinking that it’s just the two of them and that’s what it’s going to be. Then the curtains open and there’s this set behind it with a bunch of other characters. Suddenly, they burst through the back wall of the theatre and there’s this incredibly long corridor that goes back forever. The set was gorgeous, amazing—all these doors along the walls; it’s the best set I’ve ever seen. They’d created a world for all these weird people on a cruise ship! The run kept extending because it was packed every night. People went so bananas over it. I think it was literally the first night after I saw it that I started running the sound and lights for the show.

BLVR: How long did you do that for?

YJL: The rest of that extension. That was my first time backstage in a theatre, and I was doing the sound and the lights on a board that didn’t quite function very well.

BLVR: Was there someone calling the cues?

YJL: No, just me doing it visually, after, like, one day of training. The show was really design-heavy, and everybody was going crazy because I was doing such a bad job. But I was also doing it for free! So that was my first theatre experience—

BLVR: Were you really great at running the lights by the end of it?

YJL: No! I think I even made a mistake on my last day. It was so hard! My gifts are not in that area, anyway—I would actually say the extreme opposite. Through NTUSA, I met a company called Radiohole – that was another small ensemble company – and I interned with them for about two years. Like NTUSA, they do all the writing, acting, directing, designing. I interned with them for two years, going to every single rehearsal, every single performance, and that’s how I learned how to direct.

BLVR: Being in school is such a quiet endeavor. It’s a different thing for your brain to do, to go from reading and writing to being in space with people, talking and moving all over the place. Did you take to it easily?

YJL: Before I came to New York, I’d never had the feeling of belonging anywhere in my entire life. I never had a group of friends because I grew up in a really small town where everyone was white. I never had a group of friends that I fit in with, and I didn’t fit in in academia. I literally just never had the experience of feeling like I belonged where I was. It was this feeling of what am I even doing in this world? It makes existence very difficult when you feel like you just don’t belong anywhere. The second I was involved in any aspect of theatre I was instantly flooded with this feeling—like a fish in water: I can breathe! I know what I’m doing! All of my instincts are valued here! It was the first place I’d ever been where everything I was, was valued.

BLVR: When you encounter that, you flourish in ways you never thought possible.

YJL: At the end of my first year in New York, I wrote and directed my first play, Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals. After that, I had a career. Prior to that, it was just a lifetime of desperation, a lifetime of never having been able to do anything that I was really good at that I enjoyed. I would say that in that first year, I probably did four years worth of work, taking it all in. Like when you’ve been starving, and then there’s that gorging period? I feel like that’s still happening. The edges of my hunger are only now starting to wear off a little bit.

BLVR: That first year must’ve felt so radical. All this energy, that up until that point had been sort of sealed off—well I don’t know, I won’t speculate.

YJL: No, that’s exactly what it was. I think what happened is I brought in this conditioning from academia. It’s almost like when athletes train in these really high altitudes where they feel fucked up all the time, and then they come down for the Olympics or whatever, and suddenly they can breathe, so they perform at a way higher level. I feel like that’s what happened to me. I was trained to do this one kind of work, and it was so difficult because I had no talent or inclination.

BLVR: Was it stifling?

YJL: It was like torture! Just imagine all the things you hate worst in the world, and then that’s what you do, really intensely, for ten years.

BLVR: I only have an undergraduate degree, and I used to feel like I was perpetually… have you ever gotten stuck in a sleeping bag? My experience of university was like being constantly smothered in a nylon sleeping bag.

YJL: Yeah, I can relate to that.

III. COMPULSIVELY HONEST

BLVR: I recently listened to a recording of Jeffrey M. Jones, Helen Shaw, and David Cote, and Jeffrey Jones described an earlier work of yours as being “a piece of frenzied, agitated thought.” I loved that description because that’s what your writing, particularly LEAR, has always sounded like to me. Did you find academic writing restrictive in that regard?

YJL: I am compulsively honest, and in academia, there’s a lot of bullshit. Arguing a thesis felt like lying—to make any single argument about anything involving literature seems crazy. To say “This is my interpretation” is in itself saying “This is my truth,” and I don’t think I could ever put that in writing. If you asked me what I thought about a play, I could give you my opinion, but I wouldn’t be able to put that opinion in writing, point-by-point, and make it official. Whenever I talk to any academic person, I never have any idea what they’re talking about. Except for my dissertation advisor, Stephen Booth. He was a complete dream and I loved his writing. He was what kept me in there.

BLVR: So is drama some way for you to stage multiple arguments?

YJL: Yes, that’s exactly what it is. The one thing that’s been consistent throughout all of my shows is that there’s not a single argument in them, ever. I’m not trying to make one point. I’m trying to lay out all of the conflict that I see, present it, and have you wrestle with it on your own. Theatre allows me to present information in the way that I want to.

BLVR: I wondered if in some way your production of LEAR was an answer to the academic work you’d been doing—to your unfinished dissertation.

YJL: Maybe, but I don’t think that was intentional. My thesis was a comparison between King Lear and its anonymous source text, King Leir—about how we associate greatness in works of art with challenge. The original was such a crowd-pleaser; it just zipped along. It was funny and entertaining and you never got bored. Shakespeare’s Lear is really messy and challenging and there are things that don’t make any sense. I do think my LEAR ended up being by far my most challenging work. It was the first time I’d had really mixed audience responses. Even though it was more fun to have a show that people loved, like The Shipment, I feel like there’s a connection between longevity and something that you really have to wrestle with, and LEAR is the play of mine that you have to wrestle with the most.

BLVR: Were there any particular challenges in adapting a story that you knew so intimately?

YJL: All of the things that I was trying to do in LEAR were reflective of my sense of what tragedy is, and what a big play is. It was an homage to the original – not trying to be as great as that play or anything – just trying to get into the spirit of complexity and madness and tragedy and the wrenching language of despair. My voice is mostly comic, and it was my first time working with tragedy.

BLVR: The first three quarters of LEAR have the characters outwardly dealing with, or acting out their grief. Then there’s the Sesame Street part, which is one of the most straightforwardly sympathetic scenes: the “Mr. Hooper’s not coming back” line, all the characters hugging Big Bird—it’s a more familiar feeling of being “moved” or “touched.” One of the reasons the play’s so wrenching is because of these really assured shifts between comic and tragic moments. It’s hard to tell whether it’s the right moment to cry. It’s not easy that way.

YJL: I would say that LEAR is a play that’s still over my head. I made the show, but when I watch it, I have the same experience that my audience has. I struggle with it. And that was sort of my goal—to write something that was big enough that I couldn’t control it.

IV. “ARE YOU HAPPY THAT YOU’RE WHITE?”

BLVR: You mentioned that you see yourself as a comic writer. How do those comic moments come to you?

YJL: I have a really bad attention span. It’s terrible. When I’m writing, I get bored constantly, so a lot of those weird non-sequiturs come out of the fact that I just got bored with the conversation that the characters were having. In Songs of the Dragons Flying to Heaven, the white couple are having this conversation, and suddenly one of them says “Are you happy that you’re white?” and that was just because I was writing their conversation and got bored of what they were talking about.

BLVR: It’s not necessarily comedy, but it is penetrating in a way that’s comic.

YJL: And it’s silly.

BLVR: And that’s totally the way conversation goes! There’s always the outward dialogue, and then the thing going on in your head, which sometimes pops out at the wrong moment, or the right moment, starting a whole new conversation.

YJL: But in plays, that’s not common. People tend to finish out the dramatic arc, and follow the logic of whatever they’re supposed to be talking about.

BLVR: I read an interview where you mentioned something that Dave Chappelle said about being wary of the wrong kind of laughter from an audience. How do you control laughter?

YJL: In The Shipment, in the stereotypes section, where they’re all playing drug dealers and stuff, we reacted by not holding for laughs. So whenever the audience laughs, they cut off the next part of the dialogue. It was interesting because the audience gets trained to know that if they laugh, they’re going to miss the next part of the section. Once they learn that, they try not to laugh so they can hear what’s going on. That’s one way to control it.

V. “I’M BUILDING A TRAP TO TRAP MYSELF”

BLVR: How does your audience fit into your construction of a new work?

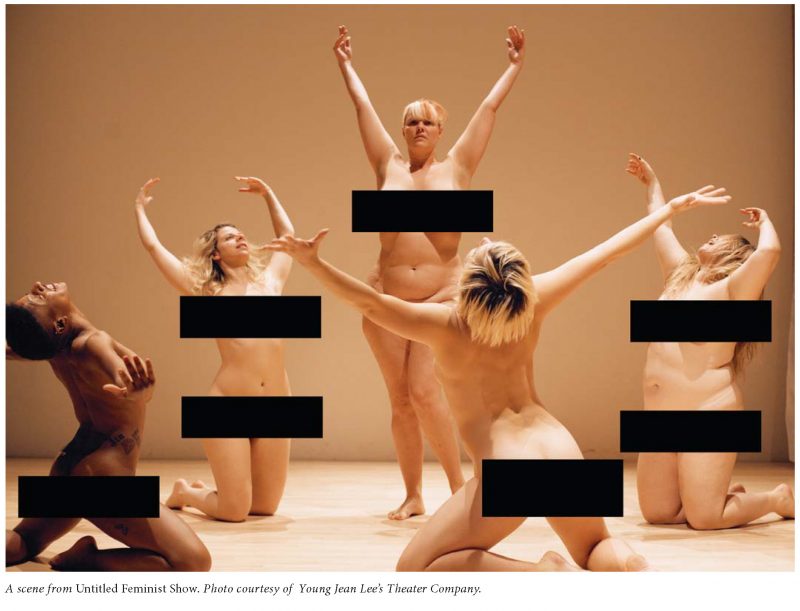

YJL: I see every one of my shows as a trap. I’m building a trap to trap myself in, and therefore my audience. Wherever I go in the world, wherever I bring my shows, it’s almost always a similar audience: college-educated, liberal artsy people who go see experimental theatre in an experimental theatre venue. People like me. If I do an Asian American identity politics play, I know exactly how I’m going to respond to that: I’m going to respond like I think I’m more sophisticated than that, and that’s going to be my m.o. through the whole show. I’m going to be like, “You’re preaching here, I’ve seen that trick done before.” There’s an impulse to categorize and dismiss, and so when I make a show, every step is basically about shutting another door. I’m working on this feminist show right now, and we’re trying to slam shut all the doors that people can escape through by saying “I know what that is,” and dismissing it.

BLVR: Can you give me an example of one of those doors?

YJL: Say a performer was to start complaining about how sexist men are—we would lose maybe 80% of our audience. They’d be like, “Oh my god, it’s a feminist show and it’s all about how awful men are,” and the gate slams shut. Or if we show someone talking about her experience being raped in an intimate one-on-one way, then a huge percentage of the audience is going to think: Vagina Monologues. The only way to keep people from doing that is to make it impossible for them to identify at any given point what it is they’re watching. Then the second they think they’ve identified it, it immediately shifts to something else so that they’re constantly sort of unstable and therefore open and vulnerable to whatever the show’s content is. The objective of the Untitled Feminist Show is to get people to be open to a feminist work, and I can only do that by keeping them off-balance. My shows are all about the relationship with the audience. I feel kind I have a kind of combative relationship with my audience, but that’s because I am my audience.

BLVR: You’re in the trap, too.

YJL: Exactly. I think that I am incredibly rebellious against genre.

BLVR: You’ve said in the past that you often begin a project by writing the worst thing you can think of. Is that still something you practice?

YJL: Yes.

BLVR: What makes something the worst to you?

YJL: If it feels like something that people are going to hate, that’s the really bad idea to me. I would say that pretty much every single one of my shows falls under the category of ‘bad idea’. If you were to describe the concept, it sounds terrible—that’s why I always have trouble pitching stuff! Because it always sounds terrible.

VI. SHE’S MY OTHER HALF

BLVR: You work as a director/writer now. Do you write with an awareness of how you want to stage it?

YJL: I do the writing and the directing at the same time.

BLVR: What would a typical rehearsal be like for the Untitled Feminist Show?

YJL: Well, there’s no text—it’s a play without words—so we’ll come in and I’ll have an idea. For example, I’ll say, I want everybody to just start humping—just being really sexual with each other. They’ll do that terrible idea, and then we’re like, Okay, what was interesting in that? And we just keep shifting it and shifting it. I’ll continue changing what they’re doing until I get to something that’s interesting to me. I work with an associate director, Morgan Gould, who’s my right hand person. She’s not an assistant: she’s my other half. And the cast is constantly improvising, coming up with new ideas. I’m also working with this really brilliant choreographer named Faye Driscoll—she’ll come in and we’ll show her what we’re doing, and then she’ll help us play around with it.

BLVR: How has it been watching with an audience?

YJL: We’ve been having test audiences come in and getting their responses—asking the audience survey questions after every number that they see. Constant focus groups. The performers also give feedback. I would say that this is the most collaborative show that I’ve ever done.

BLVR: Is that sort of collaboration something you plan on continuing in your future work?

YJL: Every show is different. Because we were pursuing feminism, the idea of this hierarchical thing – me being The Director, telling them what to do – it felt antithetical to the spirit of everything we’d been talking about. UFS had to be that collaborative. The next show after this one is my Straight White Male Show, so who knows what that’s going to be!

VII. THE BOAT WOULDN’T GO

BLVR: How do you manage all the different parts of running a theatre company?

YJL: Making art is so incredibly difficult. I would never be able to write one of my plays alone. I have a dramaturge who I’ve been working with for nine years and I’m on the phone with him constantly. I get so much feedback from audiences, from my actors, from my associate director. Anybody who looks at my body of work is basically looking at the work of all the people who supported me and contributed. I feel like the only reason I’m able to make it is by basically working backwards. I do it by scheduling a production that has to happen: the grants have to be written for it, the advertising and marketing have to go out for it, rehearsals get scheduled, actors have to be hired and paid. I’m motivated to write is because I have to, or else disaster will ensue.

BLVR: I always imagine playwrighting as being a lone, lonesome thing where you’re sitting with your computer in a little room. But you have this network around you.

YJL: It’s almost like I’m the captain of a ship. If I were just standing on the ship as a captain, the boat wouldn’t go anywhere. I wouldn’t even know how to operate it. Although I guess the captain of a ship would know how to steer the boat…

BLVR: They might know how to steer, but they’d have people helping them navigate… I don’t know… I’m not very nautical.

YJL: Me neither. I shouldn’t have gone down this road.