Brian Chippendale wears a green, lucha libre–looking mask when he drums. He sings and screams, too, but you can’t see it, since the microphone is strapped to the inside the mask and the vocals are processed into a jungle of knotty feedback. He’s usually set up in the middle of the audience, where exuberant fans flail and sweat all over him. Both in Lightning Bolt, his longtime duo with bassist Brian Gibson, and Black Pus, his solo project, he plays loud, abrasive music that floats between metal, punk, and maximalist jamming. In concert, the abstract wall of sound instigates both moshing and the sort of transcendent elation achieved only with frightening volume levels. Noise tends to be the word most often used to capture Chippendale’s style, and he is understandably conflicted about the term.

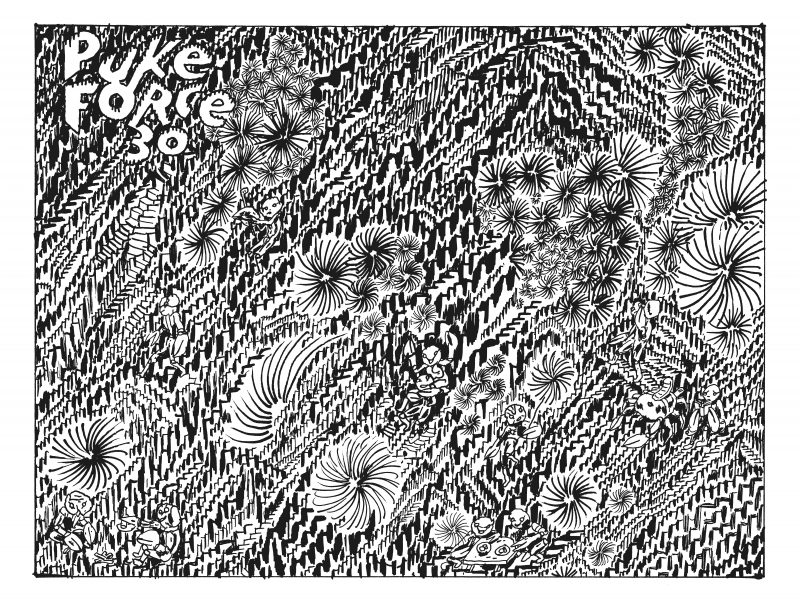

His visual art bears a similarly electric aesthetic, and is always found on the cover of his albums. Where gunshot snare-hits fill every moment of his music, scrawled, inky marks cover every centimeter of his art. Chippendale’s work forks in two directions—narrative, black and white comics, and abstract, colorful collages—though both emerge from his obsessive illustrative technique. His comics (Ninja, Maggots, If ’n Oof, and Puke Force) are experiments with varying forms, sizes, processes, genres, and mediums, from online strips to science-fiction tomes. His layout often betrays typical left-to-right reading, and he sometimes draws over found texts, creating a woozy, disoriented feeling as the reader stumbles through his absurd story lines.

Much of Chippendale’s style was born during his time at Fort Thunder, a Providence warehouse space where he lived and worked after leaving Rhode Island School of Design. With artists Mat Brinkman, Jim Drain, Leif Goldberg, and others, Chippendale constructed a maze of installations—the walls and ceilings spray-painted, wheat-pasted, and inundated with cultural debris and music gear. Since closing, in 2001, the space has become legendary among underground comics and music enthusiasts, its aesthetic now found in museum exhibitions and finely published books around the world.

Over the course of a year, I interviewed Chippendale about the intersections of and distinctions between his art, music, and lifestyle. He often took months to respond, due to all kinds of touring and what seemed like a meticulous rewriting of his answers, but he always responded with the effusive, unwavering energy he stuffs into every nook of his art.

—Ross Simonini

I. NO I SEE

THE BELIEVER: Usually, when your name is mentioned, so is the word “noise.” Not just in reference to your music, but to your art, as well. Do you think this word is meaningless or do you have an interest in the noise of the world?

BRIAN CHIPPENDALE: Drawn to the noise of the world? I actually don’t function well in a noisy environment. I try to keep my life as simple, as noise-free as I can (though I seem to have a high tolerance for mess in the house). I dropped out of college because I couldn’t take more than three classes at a time without getting overwhelmed. So, noise and me? I think the music industry, or the art industry, can’t deal well with people who cross borders in terms of media or genre. Noise is a catch-all phrase for overwhelming stuff with abstract elements or “energy,” elements involving harsher tendencies. But really—noise? Noise? What does that even mean? I put “Noise Music” on sometimes because it builds a wall that drowns out the singular sounds that people make—conversations that can leak into your thought process through a wall, through the floor. This winter I was drawing in a sunny window, solar-battling my 44 degree house interior, when a violent conversation broke out below in the parking lot. A handful of dudes screaming at each other about I don’t know what—a party they went to? An M16 assault rifle? They weren’t fighting, they were just psyched and loud. But it wasn’t noisy—noisy is abstract. I think I might be “loud,” but I’m not that “noisy.” Most likely I am just sick of the term. It’s an empty, abused word at this point, not unlike “fact”.

BLVR: Would you say noise is an expression of anything?

BC: Maybe we should get Sun Ra on this shit. NOISE. NO-IS-E. NO, I, SE. “NO I SEE”. I See No(thing). Noise is an action that blocks incoming and propels what’s inside out. Willful blindness. That could possibly lead to personal ecstasy, that then could be possibly shared. NO-I-SE. IS-E-NO. My name is Brian. IS-BRIAN-E-NO. Sun Ra’s spiritual guidance tells me you should ask Brian Eno.

BLVR: I read a quote of your’s where you said: “Shit builds up inside you on multiple levels, if you don’t degrease the system it clogs.” What shit is building up inside of you?

BC: I have been thinking about “introvert versus extrovert” lately. Having always considered myself an extrovert who spends a lot of time alone, I recently reevaluated and now consider myself an introvert who likes to hang out with people. A subtle shift in category. If I hang out with people too much without a moment, a full day here, or just an hour alone, I lose myself. I lose my way. My compass spins with no focus. So I take time, as much as I can, to let loose the ideas I absorb—be it “noise” or an absolutely specific phrase, a sentence that sticks, or the songs that sink into an annoying brain rotation—I try to find the time to release this stuff onto paper as a drawing or back into the air as a sound via voice or drum or whatever. Not just to degrease the system, but because I love to do it. I can’t be sure if it is the act of reassembling accumulated ingredients or just spending time focused and alone that makes me happy.

II. MORE “WORKING NEXT TO ” THAN “WORKING TOGETHER”

BLVR: What’s your description of Fort Thunder?

BC: A place where sixteen dudes and eight cats all shared one toilet and one litter box. It was the eye of a storm, or the river’s end, the delta, where all things from all places were deposited. It was so peaceful at night much of time. And people did some dramatic lighting so it had a glowing ghostly—ghastly?—quality. Part of me will never let go of that time. I go there a few times a year in dreams. My friends from that period, my roommates, will always hold a special place in my heart. We were lucky as shit that we didn’t burn the place down. It was a good dance club, it was a living organism. It changed all the time. Fort Thunder was my 20’s.

BLVR: Was there any precedent for Fort Thunder? Or did it come about without much intention?

BC: Mat Brinkman and I went to loft party in probably ‘92 in a Providence mill that some RISD [Rhode Island School of Design] kids lived in and we were like, “This is awesome, we have to do this.” I think Zen Guerilla was playing, and maybe Glory Hole—a wild RISD band. We found an old mill for rent to live and play music in, and suddenly it opened a decorator’s urge or need in us. We could provide a home for the “little buddies,” the toys that you find in the streets. Drag home enough shit and soon you have to come up with advanced storage techniques to display it. I had seen Allan Kaprow’s book “Assemblage, Environments, and Happenings.” Take a look at that book if you can find it in its cloth-covered hardbound gorgeousness. It will explain things. Take a touch of Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zones. Throw in a little Pee-Wee’s playhouse for the kiddie angle—not that I watched that show much when I was a kid, wish I had. But even with those slightly remembered guides, we never made a conscious effort to do anything but make a cool place and keep ourselves amused. That was pre-internet heyday. Fort Thunder was our beginning and end. Our social network. So it just built up because we had a lot of time, a lot of junk, no money to speak of or be used as a distraction. We had an absentee landlord and a lot a lot of energy. Kids in the sandbox. Cats in the sandbox.

BLVR: Do you still live the Fort Thunder lifestyle?

BC: I have kept the aesthetic and ditched the community. Which is most likely the completely wrong message to take out of there. But while the Thunder-roommates all hung out, it was much more “working next to” than “working together.” That is sort of how my band Lightning Bolt works, and still how I function. One thread that continues since ‘95 is that I live and work in an old mill here in Providence. I like living and working in a factory building. It promotes creation. The walls and floors understand making stuff, the spirits support it. I also continue to subscribe to the basic rules of Fort Thunder:

- There is power in combining disparate elements,

- The proper way to acclimate to seasonal weather is to replicate it inside your house.

- You can Paper Mache your way out of any situation.

- Always have a secret room in which to hide from the landlord (a.k.a., the man).

- Don’t forget your childhood, and in fact, when a piece of your childhood is seen escaping from you or wandering the streets, grab it and staple it to your wall.

- If, when walking in a dark corridor, you lose your balance and find yourself falling into a large cardboard box, do not resist. And finally:

- Break yourself into two minds, one that collects ideas and conjures ideas with no absolutely no rules, and another that strictly organizes everything.

III. THE FLAG FOR THE NATION OF SELF-IMAGINING

BLVR: How does the writing process work with Lightning Bolt? Do you plan or talk about music when you’re writing? Or do you just play?

BC: We talk the whole time we write music, but we play so loud you can’t hear any of the conversation! Hahahahahahhahha! No. We don’t say shit. If we say “let’s write a disco song” before practice, then we play country music. If someone wants to have a prog day, the others most likely are in a Stooges frame of mind. The lucky days we land in the same dimension are usually the days that we make a song that sticks. It’s all jamming, jamming and jamming. Then we go back and listen to rehearsal recordings. I take notes on them and we try to rekindle the peaks. We are that kind of band. No planning to speak of.

BLVR: The drumming in Lightning Bolt feels so in-the-moment. How much is improvised? How many of the 12, 389 ghost notes on the snare are composed?

BC: Did you say “ghost notes”? Let’s talk loud drumming. I don’t play or plan ghost notes in Lightning Bolt. They play themselves if they feel the need. In Lightning Bolt, in a band where the bassist brings 7000 watts to the party, every hit has to cut through. There is no subtle shit. If you are hearing subtle things in the recording, they are an accident. Not that I don’t like subtle, I love it. I just hate watching a loud band with a drummer doing complicated shit that you can’t hear. Drums aren’t mime! I’m not interested in chops for chops sake. That’s my loud drumming rant.

For me drumming, is attempting to place yourself into the root of the rhythm and then playing around that. And attempting to place hits into the beat that drive motion forward—that propel. Most of our live shows are quite rehearsed, but music is a thing you learn so you can forget it. The moment has to supersede the structure. It has to. We don’t break out much past the lines of our plot, but we change the script each night. Different nights, different ghosts, different ghost notes. Ninety-five percent of our music is written-through improvisation. I do what I want, Brian Gibson does what he wants, generally after a little while, depending on the stubbornness or spaceyness of the evening, we eventually begin to listen to each other and have a musical conversation.

BLVR: What’s the function of wearing a mask when you play with Lightning Bolt?

BC: The mask turns off the lights for me, so I can make faces in my private darkness. And it’s a separation between me and me. It’s the uniform, the flag for the Nation of Self-Imagining. Under that mask is a performer, and I am watching this stranger create as well. You know, X-men, Fantastic Four. They don’t put on the mask to hide their identity, they put it on to get in the zone.

BLVR: What has the solo project, Black Pus allowed you to do that being in a band has not?

BC: Black Pus allows me to ditch the blues, the static note, ditch democracy and really sing. It’s total freedom. There’s no, “Let’s go left to get to the destination, no, I think right would be better.” There is no hesitation, unless hesitation is the name of the song.

IV. INFO PILED ON TOP OF INFO

BLVR: In your blogging, you’ve taken on the role of a sort of comic critic. You seem to be following comics as both an avid fan and as a writer with discerning taste. I don’t know much about the world of comic book criticism but I’m curious if you do: do you read much comic book criticism?

BC: Are critics just writers looking for a muse? I am. I have fallen off the boat of comic’s criticism. I started because I was reading a lot of mainstream superhero stuff, but the indy scene I am roughly associated with was only talking about “high brow” stuff, and I found that boring, so I signed up to a somewhat mainstream comic’s forum group and started talking superheroes. And man, the people on this site for the most part made me sick. Someone would say, Brian Hitch [an artist] sucks, and I would ask, “Okay, he traces photos, but he is quite good at it and his compositions are dynamic, his stories are so readable, could you define “suck” for me?” and the dude would say, “Fuck you, he sucks”. I didn’t last so long in this group. There were a couple cool people, but for the most part I felt fairly isolated. Maybe I joined the wrong group and they ruined it for me. But I glanced at some other ones and the vindictive jackass type seemed to rule the roost all over. People are generally more interested in whether the Thing could beat up the Hulk. Fuck it, I got involved.

But now, some critics like the new wave at The Comics Journal are mushing superheroes and underground and historic all into one mashup, so I feel less like I’m needed. Plus, I ran out of time to read comics this year, or read them beyond, “Pheew, got through that one.” But I want to write some more, I like to write, I like to joke, make connections outside of the form. I like to celebrate a good work, find things I couldn’t see till I looked deeper, and I like to call people on their shit. I will write some more. And some of the superhero/underground—superunder?—critics still either say too little or analyze the shit out of a topic, displaying the full range of their well-schooled vocabulary. I make it fun for the man on the street—not to dumb-down criticism, but to enjoy the spring air without the weight of class warfare. And also to make a thing, a written piece is a thing—a work. I like to make work.

BLVR: Your books play with the way comics can be read. Ninja forces the reader to squint, or to at least slow down their reading. Maggots requires the reader to excavate the story from of a darkness of black ink. If’n’Oof has a different flow—more like an art monograph, with a page per image, allowing for a more expansive reading experience. Is this a pretty conscious choice, to direct the reading?

BC: A main point of my comics work, and possibly the string that holds the sweater together, is pacing. I can see the work for its differences—the scale, the density, whether or not there appears to be a story—but I also see it for it’s similarities, and that would be its concern for pace, its interest in motion. As a drummer, I am concerned with the beat, keeping the beat going. That’s why If’n Oof is such a long book, where not a ton of heavy duty stuff goes on. It’s a lot of real-time motion, a lot of walking, with explosions of story here and there. It’s kraut rock with psychedelic bursts. The reading back and forth that I apply on everything—save If’n Oof—was me thinking that it made sense. I didn’t want to fuck with the form or experiment for the sake of experimenting. I just saw a fundamental flaw in the way the eye is trained to read, and I corrected it. So the form comes out of function.

Also, my comic work is idea driven. I would say most mainstream and much underground comic work is character driven. If you take a basic 4-6 issue trade paperback collectable arc you get one idea per roughly 120 pages, and a character deals with this “idea.” In Puke Force I try to squeeze at least one idea onto each page, and many times more than one. I’m not trying to compete with the form. I think they are both valid, and in fact I complain about many superhero comics because they are character-driven stories that don’t have any character building in them. And here I am, truly not a strong character-builder myself, so it makes me a hypocrite, of course. A hypocritic. But it’s still true: you can’t make 120 page books driven by stiff wooden characters. Unless you call them If’n Oof. Hahaha!

But anyway, ideas form the bulk of my comics – from brainstorming. Like on tour while driving across the barren plains of Utah with LB, I had a vision of a new corner store, the “Thousand Mile Stair Storefront,” where people walk humongous stairways while looking though lenses that either imitate vast distances or can see through walls for vast distances. This would be an ok pun for one thing – “stare” and “stair” – and also a necessity in a city, where people don’t get to see far enough, stretch their vision. And also it’s cardiovascular. I’m into this sort of double entendre stuff. It’s something comics are good for, IT’S mushing ideas up, designing things that can’t exist. I’m drawing. When you’re drawing it’s great to create, not necessarily capture.

V. “ I JUST GET DOWN ON MY HANDS AND KNEES AND BEG THE SHIT TO FORM SOME COHESIVE UNIT”

BLVR: Can you talk a little about the process of making one of your paintings? They seem to be fully collaged, but how do you come to these collages and choices? Do you have a bucket of cut-up drawings you’re working with?

BC: A bucket? I’ve got a full 20 by 20 foot room, wall to wall, of torn, cut, scribbled-on, printed, smeared paper, half drenched in cat piss and sweat and who knows what else. Dead bugs squashed in with the hairs, dirt and flecks of skin. I’ve got boxes of collected papers, my art shredded into cereal flakes, other peoples’ art, letters, flyers that just weren’t cool enough to save or are so cool they need to be absorbed directly. I just get down on my hands and knees and beg the shit to form some cohesive unit. Really, it’s me cleaning all the damn scraps up and gluing them somewhere to keep them organized. I used to tell little stories, like paper dolls in scenes—comics in a way. Now I am trying to move away from straight narrative work in my larger collages/paintings/drawings; Trying to see the work for what it is, let a line be a line, a blob be a blob. Comics are for stories. Art is for letting materials breathe together.

BLVR: I’m curious about how you feel about the physicality of drawing versus drumming. Your paintings feel busy but also meticulous and careful. Your drawings, on the other hand, seem like you’re stabbing the paper. And the drumming is obviously a full-body experience. How the physical side of things affects what you make?

BC: Believe me, I have tried to mesh the two practices. I have a pile of demolished Rapidograph pens with smashed tips to prove it. It’s just different stuff. Some rooms you slip into and some you dive into. As long as you get in there and stay in there, it’s good.

BLVR: A lot of science fiction worlds exist on the level of metaphor – a fantastical world illuminating aspects of our own world. Does the world of If n Oof work on the level of metaphor for you? Or is it more about the act of just creating a new world?

BC: I don’t necessarily love metaphor as a key player in my work because it can take away from the quality of experience the characters are having. I wouldn’t want If and Oof to find out they are only representing an idea or other situation. I respect them too much for that. Metaphor is great as an inspiration, a tool to get going or get past problems, but once the ball is rolled, the game has to get serious on its own terms; it has to be grounded. The goal is to create worlds that can be believed in as actual places—places that continue even when the story is over. If ‘n Oof reflects the “real” world in terms of dealing with transformation, manipulation, time, perception, and/or relationships, but the story isn’t a stand-in to explore any one of those things specifically. I am too unreliable a creator to conjure up a greater metaphor and stick with it. I would inevitably betray it.

BLVR: Some of what we’ve been talking about – Fort Thunder, mask-wearing, alternate sci-fi worlds, comics – it has a whiff of escapism. Is there anything wrong with escapism?

BC: Escapism? Damnit. Is that what it is? It’s not a legitimate stance against a tidal wave of garbage? Against the The Cheap Garb Age? Escapism? I think escapism is healthy. every time you cast a thought forward or look to the sky you are escaping. I don’t think of escapism as something outside of yourself; it’s something natural and fundamental, like breathing. Everything we have was “escaped” into creation right? Ideas flee the prison of the mind, become real. I believe in it as much as I believe in riding my bike or laying in the grass or digging in the dirt or eating bread or drinking water or skinning your knee. It’s key. If you paint a room pink, are you escaping from the previous color? When the music is cast, that’s where you are—no yesterday, no tomorrow. You’re in the pink. Escapism here is training for the next world, where perhaps a new set of skills will be necessary. Training for tomorrow where up will be down. Escapism de-rigifies the mind. And it’s fun.