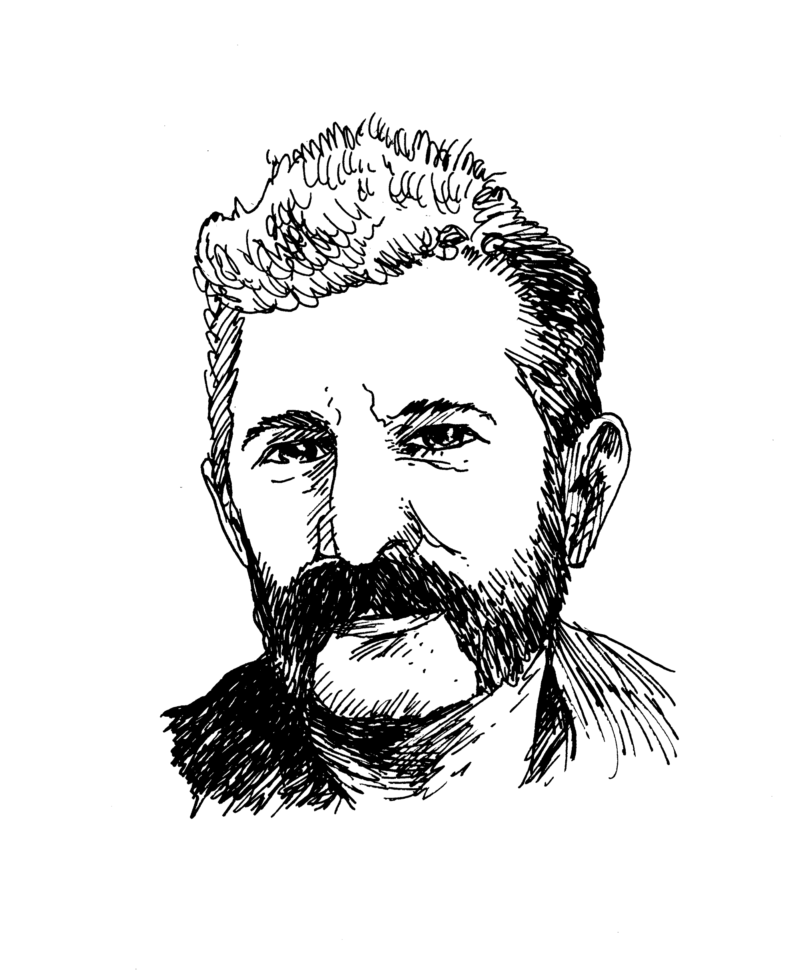

I first met Sandor Ellix Katz a decade ago, outside of Nashville, Tennessee, at the fermentation workshop kitchen and queer intentional community where he then lived. Wild Fermentation (2003) was already a best seller, and his views on food activism had already had a huge impact on my life. I’d started growing more of my own food, fermenting a good deal of it, volunteering for local food organizations, and in 2009, several months after I met Katz, I cofounded the annual Portland Fermentation Festival, at which Katz spoke.

Fermentation is the process by which microorganisms—bacteria, molds, yeasts—break down food and drink and by doing so preserve them and make them more delicious and nutritious. Some food and drink ferments beloved worldwide include cheese, leavened breads, cured meats, wine, soy sauce, miso, sauerkraut, and sour pickles.

Since 2009, Katz has written The Art of Fermentation: An In-Depth Exploration of Essential Concepts and Processes from around the World, which won a James Beard Award, taught hundreds of workshops internationally, and presented at Terra Madre, Slow Food International’s conference in Italy. Throughout all of this, Katz has had AIDS. Since his initial HIV-positive diagnosis, in 1991, he has been deeply committed to the nutritive and immune-boosting sustenance of live fermented food and drink, to which he attributes, in part, his own well-being, although he shies away from any sort of sweeping fermentation health claims.

Katz now lives with his husband, Leopard, just on the outskirts of the intentional community where I first visited him. On a loud-with-crickets midsummer evening, I was welcomed into their colorful, art-filled home, and we made our way to the kitchen, where Katz sometimes teaches workshops. A huge cast-concrete island was covered in various ferments, and overhead, a beautiful stained-glass window depicted bacteria. It was here that Katz caught me up on the recent lightning storm that took out their solar-charge controller. While it got repaired, they were keeping their batteries charged by generator.

Katz and Leopard live off the grid, surrounded by gardens, with spring water and an outhouse that includes a sparkly pink flamingo toilet seat. They grow a significant amount of their food and ferment much of the surplus. The ferments I spotted that first night in their kitchen were a crock of two-week-old sake, inspired by Katz’s recent trip to Japan, a container of radish kimchi, and a gallon jar of turmeric vinegar.

Our interview was conducted over the course of three days. For some of our conversation, Katz lay down on the couch, as if in therapy, though he was too animated to stay in that position for very long.

—Liz Crain

I. “CHOP THEM UP,...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in