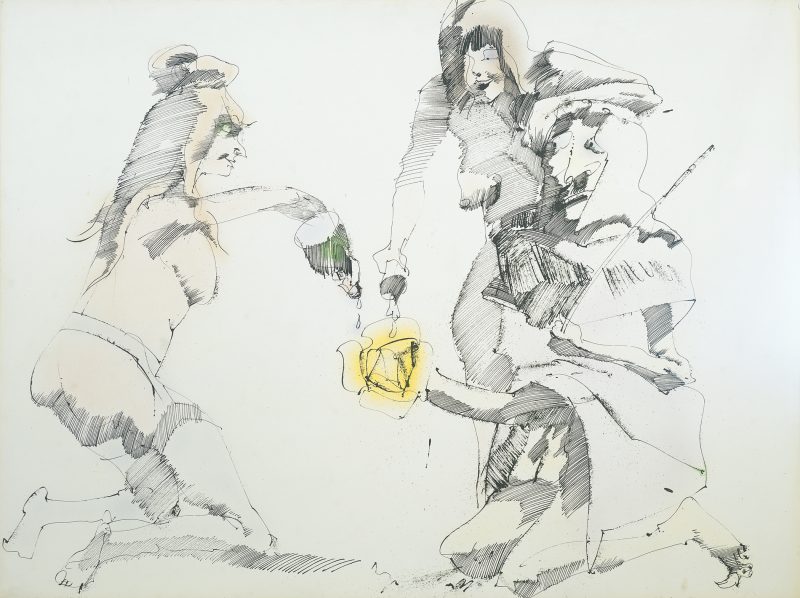

In the print my parents have always had hanging on their bedroom wall, a man and a woman are engaged in conversation. The woman leans forward onto some kind of mound or stump, her posterior exposed and turned to the viewer, a garment hiked up on her hips, while the man stands in profile to the right, his left arm tucked close to his side and the other hanging nonchalantly in the air as if conceding a point. The lines making up these figures are baggy and wrinkled, while the faces, thick with doodles, less detail their features than obscure them. Both bodies are rendered in a greenish blue, an aquamarine close to blueprint, except for the surprise of the work, which is a yellow flower blossoming at the end of the man’s oversize erection. What a funny thing for parents to have in their bedroom!

As far as I can tell, the work is untitled. Dated 1967, it was made in Los Angeles by the artist John Altoon, who died two years later of a heart attack. Altoon is a minor if storied character in L.A. art-world lore, having moved in the guy-centric circle around the Ferus Gallery with figures like Wallace Berman, Edward Kienholz, and Robert Irwin. “If the gallery was closest in spirit to a single person,” Ferus’s suave proprietor, Irving Blum, later said, “that person was John Altoon—dearly loved, defiant, romantic, highly ambitious—and slightly mad.” This is the kind of retrospective compliment paid to those who evade success—emblematic because elusive—though it seems that Altoon was indeed an energizer and merry prankster. If Altoon’s way of life personified the gallery’s spirit, however, his aesthetic was nevertheless apart from it. Though he contributed to Berman’s Semina, a beat publication composed of loose leaves of pictures and poems and sent to friends, his black-ink drawing of a priest hovering over a dead child stands out from the funky photographs and peyote paeans surrounding it. Indeed, Altoon never pursued a mythic, holy function for his art like Berman (who was arrested at his 1958 one-man show at Ferus for displaying biblically infused “pornography”) nor did he make politically provocative tableaux à la Kienholz (whose Back Seat Dodge ’38 [1964] was a cause célèbre). Unlike Irwin, he never explored the cool intricacies of optical perception. In many ways, Altoon had more old-fashioned ideas about being an artist. He put together serious-looking...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in