I. Yellow Roses May Be All He Can Bring You.

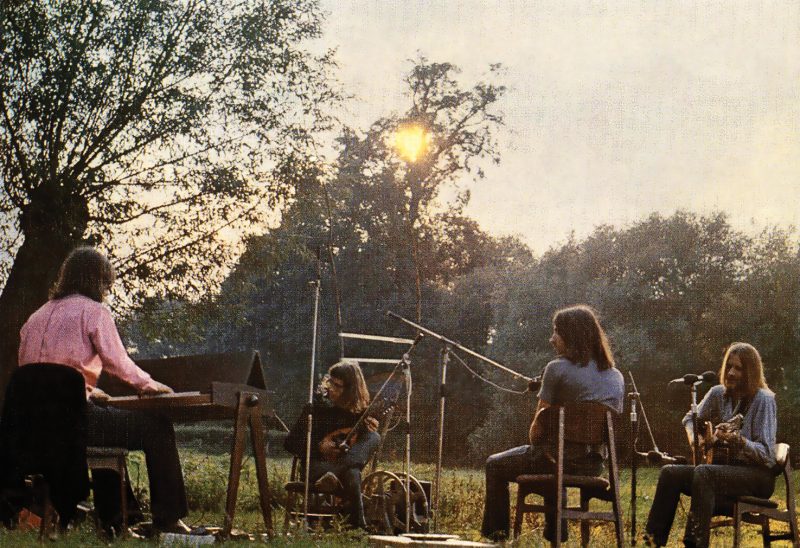

Sometime back in 1970, four newly signed musicians decamped to the middle of the English countryside and proceeded to record their first album al fresco. If you ever take a train between Oxford and London (change at Didcot), blink and you might easily miss the place where it happened. The village of Appleford amounts to little more than a signpost surrounded by farmland, with a crumbling church tower barely visible beyond. There are no blue plaques designating the site as in any way extraordinary. Yet, if you do manage to catch a glimpse of the place as it whips past the windows of a Virgin express train, you should tell yourself that this was where, some forty years ago, British pop music took a deep breath between its psychedelic comedown and the arrival of stadium rock. This was the locus of a short-lived strain of acoustic music of almost avant-garde vulnerability and gentleness—the equivalent of what Erik Satie might have sounded like to throngs of Beethoven fans and Wagner nuts. Out in the middle of that field is where autumnal folk had its definitive moment. That it drifted away as quietly as it came is perhaps part of its appeal and enduring mystique.

There he stands on the farm

With his eyes on the windmill

And his head goes round and round

Like the hours of the night will

The album begins with a song called “Yellow Roses.” Over the sultry hush of the countryside, a piano begins by caressing a simple music-box melody—nostalgic and heartrending all at once. A guitar and then a mandolin follow suit, their harp-like arpeggios slowly building. Then the voice: not streamlined or affected, but a frail human voice, almost sighing the bittersweet tune. The chorus comes, the song opens up. A two-part harmony wafts in like tumbling leaves before a third voice, equally vulnerable, takes up the next verse. And you realize this is one hell of a radical way to begin an album amid the musical landscape of 1970, even for a folk-rock band. This is the sound of the dawn breaking, intermittent birdsong and all.

Put plainly, “Yellow Roses” is one of the most impressive British folk songs of the era. Its unpolished, pastoral beauty is astounding, its vocal harmonies all the more moving for being faintly imperfect. It’s as if Alan Lomax had wandered into an English village and happened upon a band of locals as fluent...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in