During the first few minutes of the screening, someone behind me whispered: “Is this for real?” It is one of my favorite questions, because it usually indicates that something interesting is taking place, or about to. Like all rhetorical questions, it is redundant—there is nothing that isn’t for real—and its primary semantic thread is measured incredulity: you are, for a second, destabilized, attempting to decide what is and isn’t scripted, performed or not performed, constructed or not constructed.

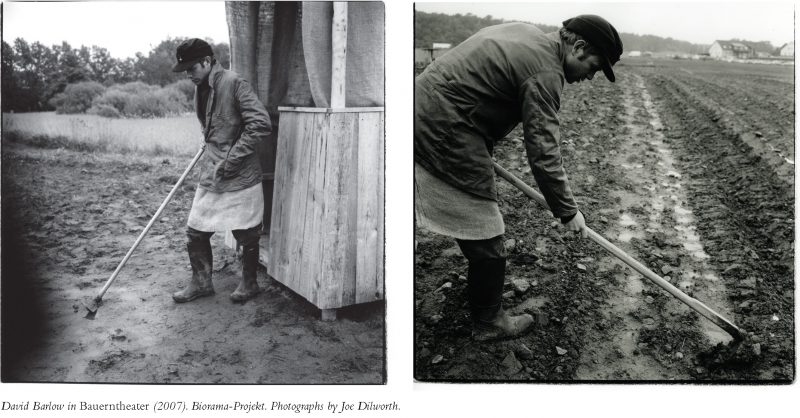

The film was a low-budget documentary screened as part of the Prelude festival of new theater in the fall of 2007, and its subject was David Levine’s Bauerntheater, or “farmer’s theater,” which had premiered in Germany earlier that spring. The film begins with an image of the stage: a large, fallow field, located near a farming village just outside Berlin. We see an actor being hired—David Barlow. A script is rehearsed—Heiner Müller’s play Die Umsiedlerin—but we soon learn that not a word of it will be used, save for the name of a single character, a potato farmer named Flint. We see rehearsals in a warehouse in Brooklyn. Barlow/Flint stomps around inside a large, shoddily constructed trough filled with three hundred pounds of dirt in order to practice, again and again, the gesture of plowing and planting potatoes. Serious attention is paid to proper dress, and correct planting technique. Later, we see the actor being flown to Berlin for the performance. He arrives on the field, the stage. He goes into character, and the performance begins: for the next thirty days, for ten hours a day, five days a week, he plants the field.

Is this for real? Is it acting if you have no lines, no theater, no stage, no ushers? “Is it still ‘acting,’” Levine asks in his introduction to the Bauerntheater catalog, “if you’re doing manual labor? Is it manual labor if you’re ‘acting’?” And finally: “What does it mean to spend more hours of a day as someone other than yourself?” Much of Levine’s work interrogates conceptual terrains to a point where they momentarily annex each other. Labor isn’t just foregrounded. It’s literalized so that it becomes a metaphor for just about everything we do: rising out of bed, brushing our teeth, going to work, or, if you’re a beginning artist, sending out your work to galleries, magazines, cultural institutions.

In July the Berlin gallery Feinkost will premiere Levine’s Hopefuls—an exhibition of Levine’s ongoing attempt to salvage discarded unsolicited actors’ head shots and cover letters—and this exhibit will travel in the fall to Cabinet magazine’s Brooklyn project space. An upcoming piece, Venise Sauvée (opening in March at P.S. 122), takes as its starting point an unfinished play by Simone Weil; normal theater stagecraft will be switched out for the format of a seminar, and actors, writers, director, and audience members will collectively explore—as the performance—the function of political theater within so-called Western democracies.

After seeing the premiere of the Bauerntheater documentary, I found myself in Berlin, where Levine lives part of the year and where he is the director of performing arts at the European College of Liberal Arts. He had recently moved, and his new apartment was mostly unpacked boxes and a few pieces of furniture. We sat on the floor with an old-fashioned mini tape-recorder between us, and talked.

—Christian Hawkey

I. “SO-CALLED REAL TIME”

CHRISTIAN HAWKEY: Your work traverses a number of different artistic fields—conceptual art, performance art, land art, theater—and it strikes me that the reason for this is your interest in the gaps that open up when different modes of representation are placed in dialogue with each other. It’s as if a given work becomes more real, more readily experienced, when it’s not easily locatable within a single genre.

DAVID LEVINE: I think the conventions of spectatorship are just as powerful as artistic conventions, if not more so. You go to a gallery with a certain expectation that you’re going to look at things a certain way. Same with theater. Same with films. And over time, these conventions calcify. The only way to make your experience of things come alive is to short-circuit these institutional conventions. What I’m making isn’t necessarily more real, but hopefully your encounter with it is.

CH: Take Bauerntheater, one of your latest projects, for example. When you pull a single character named Flint out of a Heiner Müller play, a character who is a farmer, and place him not on a stage but on an actual potato field, where the actor playing this character must, in order to “act,” commit to the labor of farming for a month, the conventions of theater are blown open to include all sorts of other discourses. One immediately apparent theme is the question of labor, of work, which is always hiding behind all cultural productions.

DL: One of the basic notions of theater is that it’s special, and it’s only happening for you, every night of the week. But if you look at it globally, and you talk to actors who are doing a show for more than three months, it’s a job. Somebody who goes to work every day, and does the same thing every day, they’re doing it at a pretty high frequency—you repair thirty radios a day, or approve thirty transactions. Theater, in comparison, is on a very low-frequency loop—once a night. And that supposed singularity is what effaces the traces of the work. But if you turn up the frequency to where the actor is performing all day long, and there may or may not be an audience, then you can actually start thinking about labor and how it goes up against hope, or the expectation of transcendence. It’s about trying. Like, I’ve got these actors’ head shots. [Gets up and disappears into next room, returning with a huge pile of envelopes, head shots, and cover letters.] It’s part of a larger project that’s gonna take about ten years. I’ve been collecting unsolicited submissions in every field of cultural production. Manuscripts. Demo tapes. Head shots. Slides (which don’t happen anymore). Videos. Films. All of which get sent to institutional gatekeepers. And then they get thrown out, and on their way out I catch them, catalog them according to cost of production, environmental impact, the amount of effort you discern in the cover letter…. The rule is that they have to be unsolicited. Unsolicited submissions—for all of us—are the most excruciating kind of performance. The work also comes out of my own experience as an artist and a certain amount of bitterness.

CH: One thought that kept me going when I first started writing was the notion that to be a so-called “failed” artist was the most radical thing I could possibly do. Even if the poems and manuscripts get rejected by magazines and publishers, you at least know that your work is not in danger of being instrumentalized by institutional gatekeepers. It was only me and the writing that I was doing. That’s partly why I find Bruce Nauman’s early video work so compelling: just this guy in a room, bouncing off of walls, trying to do something over and over, trying to endure, and doing so within his own set of parameters. I love that. It’s liberating to be comfortable with this, and not want more, or not let what you do be predicated on wanting more than the practice itself. Whatever else happens, whatever subsequent success that happens, then becomes an accident, a by- product, an unexpected gift.

DL: But it’s not enough. It’s not like it’s not disappointing.

CH: It’s true. I’ve been reading a lot of David Schubert lately. He really struggled to “break through.” It caused him an enormous amount of suffering—it broke him, in fact. His poem “No Title” contains the lines “How little space there is / Between success and nothing at all.”

DL: You always hit this moment as an artist where, if you’re not instantly successful, you say, “Well, I’m clearly going to keep doing this. I’m clearly fucked. I’m clearly impractical. I’m going to be bouncing in a corner for the rest of my life anyway, because—unfortunately—I clearly want to be bouncing in a corner more than I want to do anything else.” It’s about repetition and monotony and labor all in the service of a hope. All of the things that I do, to some extent, simply allegorize this. One of my first big projects was in this gallery, where it’s just these actors inside a box doing Broadway plays over and over again.

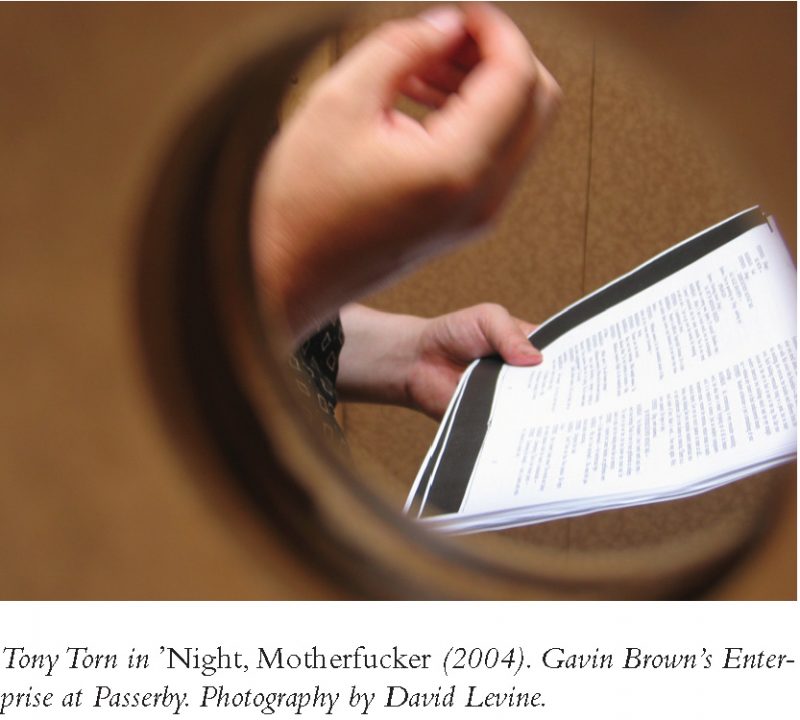

CH: That was ’Night, Motherfucker, where you constructed a huge, faux-minimalist sculpture, and then you locked two actors inside it. During the gallery hours they had to read or perform a few notable two-person Broadway plays on a loop. The two actors were also in different parts of the box, and could only see each other through a mirror.

DL: Yeah. And that was all it was about. It was about banging your head against the fucking wall.

CH: It’s also about the way the art world puts theater in a kind of box—theater placed in an actual box, which is placed inside a gallery. Your essay “Bad Art and Objecthood” talks about this irony: how performance art, in orderto be taken seriously or to be seen as “real,” is often purposefully bad theater, and, conversely, good theater is often considered bad art. I was thinking that even now in our contemporary art moment you have a resurgence of collaboration, of collaborative groups, and theater, afterall, is precisely the most “live” and spontaneous collaborative art form. A group of people, getting together in so-called real time, making something. And you even have Marina Abramovic at the Guggenheim reperforming (re-adapting) famous performance pieces.

DL: Yeah, except for theater, the process phase of collaboration, the part that gets exhibited in an art context, doesn’t “count.” It’s only preparatory to a final, fixed version. It’s not meant to be seen. In a way, ’Night, Motherfucker was as much about theater not listening to art as it was about art not listening to theater. I do and do not get why there are such distinctions drawn between art and theater. In the end, each is premised on certain markets, and these markets determine what commodities are produced. There’s no market for theatrical documentation, same as there’s no market for the actual art performances. So even if the performance is the same in both places, it exists as totally different commodities. So there’s no incentive for these disciplines to listen to each other. To ask them to listen to each other risks undoing their entire profit bases.

CH: Hooray!

DL: But they accidentally recapitulate each other anyway. Take a look at this head shot. Judy Chang. Aspiring actress. When you see fifteen of the same head shot, all smiling at you like that, it’s Warhol’s Marilyns. Minus the fame. When we talk about monotony and repetition and hope and endurance it’s all there in that look she’s giving you. [Points to head shot]

CH: To get hired you have to become a totally empty sign, so that casting directors can project their desire onto you.

CH: To get hired you have to become a totally empty sign, so that casting directors can project their desire onto you.

DL: Another interesting thing about collecting this stuff is what the conventions of cover letters are, in each field. In acting, one of the major ones is that you should tell the casting agents how to sell you, and there should be a visual link between the head shot and what type you are. You have to say what you can be sold as. I don’t mean it in a demeaning way—well, it’s beyond demeaning—but this is where the actor becomes a metaphor for the rest of us. So the cover letter has to say something like “I have been compared to a younger Gwyneth Paltrow.” It’s like pitching a movie.

CH: You’re pitching yourself by using the most accessible frames possible.

DL: Which means you’re basically hollowing yourself out. With any unsolicited submission, the idea is that you’re trying to break in from the outside. And at this moment your work stops being art, and becomes an instrument or a vaulting pole, in the hopes that once you get over the other side of the wall, once you’re “in,” then it will go back to being art. So for one moment the work becomes a professional lever, and if that’s the moment when it gets thrown out, then art is just frozen in this weird state of being a tool. That’s the state I’m interested in.

II. YOU ARE BEING “HANDLED.”

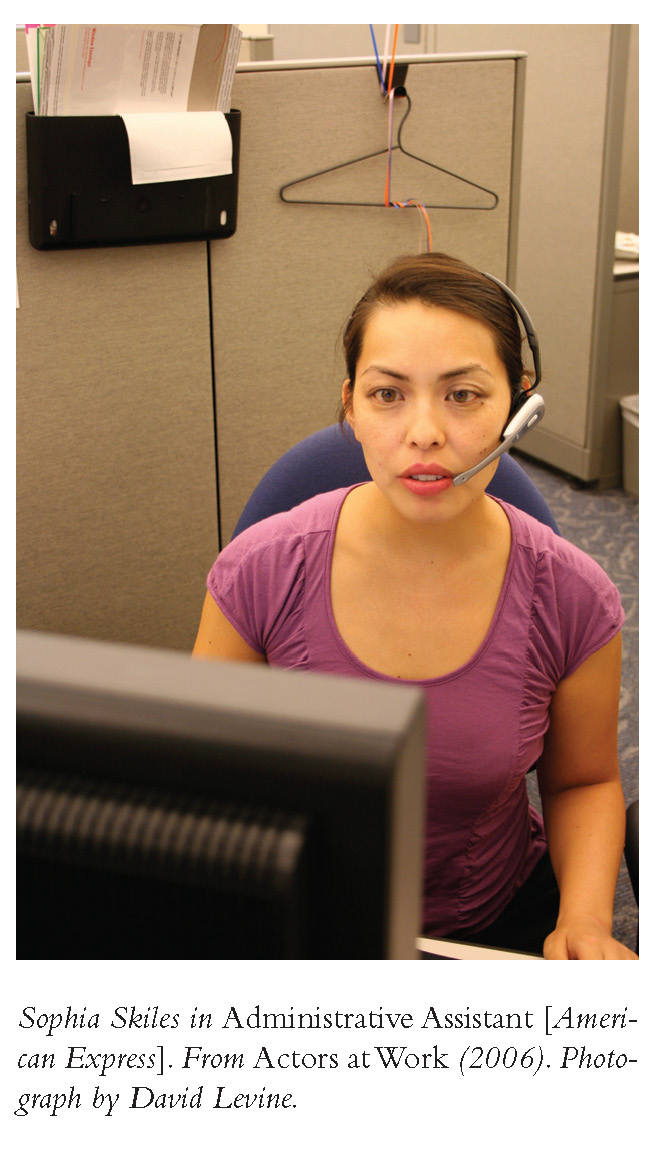

CH: It seems like much of your work attempts to make the invisible mask, which all actors wear, or are, into something present—visible. In Actors at Work, you hired actors (you paid them and filed all the paperwork with the actors’ union) to simply go to their own day jobs, the very jobs they’re doing in order to become actors, to support themselves as actors. Their day jobs became their stage. For once, they are truly working—working at working. It’s not so much about erasing the boundary between work and life, but foregrounding the labor involved in both, and how the mask is, in fact, that boundary. In Bauerntheater, the viewer standing on the sidelines watching a farmer/actor has to decide whether the sweat on his brow is the real sweat of a laborer, or the sweat of an actor, or both. To ask the viewer to consider such distinctions—who is working here, who is not working—is a generous way to ask them to be as present as possible.

DL: In my case I feel like the prevalence of theatrical conventions in other aspects of daily life is more interesting to think about than theater itself. Think about that moment of blind fury you get when you’re talking to an operator, or an airline attendant, and you suddenly realize that they are “on script,” and that you are being “handled.” All you want to do is throttle them. You thought they were actually talking to you, but actually they were not there. And yet—forget the corporate masters—the flight attendant has to use a script, because they have to keep themselves out of this. When employees are working off a script, those scripts are essential to their privacy as people. A lot of Actors at Work is really about privacy, and where you locate it. It’s not just about being unable to connect, or not being fully present, but it’s also about the way in which you keep yourself to yourself, and the necessity of that, especially if you have a job. The premise of a day job, which is implied by the term day job, is that it’s not “you” doing it. The real you comes in later, after work. When you’re at work, you’re giving the most convenient performance you can to get by. So I’m interested in the ways in which acting is not just a metaphor for duplicity or social performance or even the American dream, but also a metaphor for privacy—the part of yourself that makes you seem not present.

CH: I have spent countless hours being paid to pretend to work. No matter how easy it is to pretend, it is still alienating. Actors at Work short-circuits this alienation. That’s interesting. I don’t know that I believe in the notion of privacy—of some authentic state or self that needs to be protected—but I know I am most present when I am doing something that I want to be doing. One of your newer projects is called HABIT, and it’s scheduled to premiere at MASS MoCA. What will that entail?

DL: It’s a continuation of ’Night, Motherfucker. I’m going to rehearse a really straight play—three characters, single apartment, love triangle—the usual; only I’m not going to stage a moment of it. Once everyone knows their lines, their motivations, their relationships to one another, I’m going to build the actual apartment in a project space— working plumbing, electricity, the works—and then I’m going to have the actors live in that apartment for eight hours a day, performing the play on a loop. They improvise staging as it suits their needs, but eventually their physical needs as people—I’ve gotta shit, I’ve gotta eat, I’ve gotta watch Oprah, I’m bored—start to assert themselves under the fixed dialogue, and over their roles. So sometimes the big fight scene takes place while one person’s making a sandwich, and the other’s taking a shower; sometimes it happens when someone’s trying to read a magazine and the other one’s trying to piss. No one cleans up the set between iterations, so if you throw a coffee cup during the confrontation scene or don’t do your dishes after lunch, they’re still there for you on the next go-round. So as the actors get bored, inspired, hungry, tired, as the apartment gets messy or clean, this narrative keeps changing shape. It’s about where realism and reality overlap.

CH: I was thinking about your move to Berlin, and how you once said that it involved, in part, giving up on American theater. Is Europe or Berlin itself a better home for theater, or for interrogating this space between realism and reality?

DL: Well, you can get a little weirder for mainstream audiences here, but theaters are still theaters. My problem is with the architecture and the conventions surrounding theatergoing—everything that actually makes it theater— and those are pretty much universal. I’m doing a project for P.S. 122 in New York this March that uses a seminar format to explore the ideal of democracy; specifically, the idea of political theater. The nominal topic is an unfinished play by Simone Weil called Venise Sauvée, which is about a seventeenth-century attempt to overthrow the Venetian republic. So it’s all about when is a democracy not a democracy. But in the seminar, the actors and the dramaturges and myself and the writer are all sitting around a table among the spectators, and there is no actual center. Everyone participates. The piece tries to ask: What do we mean by “political theater”? Can theater even claim to be political in a country where theater has no impact? Theater usually poses these questions allegorically—“Y’all sit back and watch while we present a story about ‘an artist’ suddenly caught between self- censorship and speaking out.” This is how nothing gets done. And we’re like—no; just pose the fucking question directly and explicitly, and if you want your audiences to really wrestle with it, then ask them a question and wrestlewith their answer. Everyone feels a lot more alive for it. You want to talk about Israel and Palestine? Then let’s talk about it—but then you start thinking about participation, and democracy, and performance, and noticing that the ways in which people participate in a discussion are not necessarily “authentic,” or maybe authenticity is beside the point.

CH: And the way people inhabit their bodies becomes apparent. When they’re worked up, or nervous, or selfconscious, or their own subjectivity is aligned with a specific political point of view, you can see it. Emotionality becomes physical. People’s voices shake. You can hear, beneath their speech, how a sense of injustice embeds itself in their bodies, marks their bodies. I was thinking before this interview that acting is also essential to learning a foreign language. I found it easier to reprogram how I physically pronounce and articulate German sound patterns if I pretended to actually be German, if I invented this German persona, and of course in order to do this you have to confront all sorts of figures, culturally received figures, some of which define a fairly stereotypical idea of Germanness, from Klaus Kinski to Boris Becker to Ralph Fiennes playing an SS officer.

DL: Did you like this German persona?

DL: Did you like this German persona?

CH: Good question. What interested me was that this encounter, this notion of inventing a new persona, which then makes you examine all the clichés that inform it, was central to learning another language. And I also liked being aware that to change my physical speech patterns required an imaginative act—as if another language requires one to imagine another body.

DL: That’s fair enough. I still feel very uncomfortable speaking German, because when I speak it too long I stop feeling like myself. I don’t like that encounter. I should think about it more along the lines that you do. I should just embrace it. When I first got here I didn’t really start learning German for about a year, because you don’t need to in Berlin, and sometimes I would get so exhausted by my inability, and the constant humiliation of all these helpful, English-speaking Germans, that I would speak French instead. I speak French fluently. Most Berliners don’t, so if I spoke French, which none of them speak, then we would be on even grounds. One of us would have to suggest English, and then I would speak English with a French accent. It would even the playing field.

CH: It makes you an actor—

DL: —I think this is what makes you an actor. One of the things about my work is that I’m never in those pieces. I never act onstage. I’ve acted in movies sometimes, but that’s easy—you just be yourself. But what I can’t do is play a role. I lock up, it’s awful. And I will also not put myself in these performances, which is cowardiceor whatever. But you’re much closer to acting than me, because that encounter with this different persona that you talked about is something that you’re interested in, and that’s what makes an actor an actor. You are really taking a risk and embracing something that makes you uncomfortable. You have to be willing to embarrass yourself. To fuck up. This is what makes actors actors and directors directors. The thing about actors is that they can do these amazing things in that moment where they just jump in. You have to do it to learn a language, and you have to do it to play a role well.

III. OUR RELATIONSHIP TO LABOR

CH: There’s an analogy here to writing poetry. Jack Spicer said that poets think they are pitchers, but they’re really catchers. Once you understand this, you no longer direct language, but rather let it direct itself— direct you. You’re along for the ride. It is simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying.

DL: Do you know the poet and playwright Mac Wellman? He once said that his whole style of writing changed when he decided to write the worst plays he possibly could. He said it was like discovering a new continent. By “worst” he meant the most clichéd, and he said he really started to understand language and how it worked when he gave in to language, to so-called bad language.

CH: Amazing things happen when you no longer try to write something great. Ashbery often talks about giving his students the assignment of writing a thoroughly bad poem, and I’ve used the same exercises with my own students. It’s basically a way of tricking yourself out of yourself. David Byrne talks about this—about why it’s important to loosen up or relax any obsession with “purity and authenticity,” which is the fastest way to exterminate creative desire. And of course, such an exercise presumes that you know, or think you know, what good or bad writing is to begin with.

DL: This sounds tautological, but actors are the only ones who can be totally persuasive when they’re onstage. You can sneak an actor into a seminar, but you can’t take a civilian and put them onstage. They won’t be able to do it. They won’t be able to perform. An actor can. But actors make bad spies. And they also make slow farm laborers, because they take the role more seriously than the task. An actor is somebody who can lie in front of a certain formal arrangement of spectators. But anybody can lie persuasively in their daily life. We do it all the time. Same thing with really inventive emails. Or certain uses of language. Or a poem that was just written off the cuff as opposed to a poem that wasn’t. We were talking about effortlessness, and I was thinking about Frank O’Hara.

CH: Yes. He makes it look so easy, so spontaneous, which is of course deceptive, because there is a tremendous amount of craft and labor involved in creating the illusion of spontaneity.

DL: Weirdly, in terms of reception, it’s the stuff that has a huge amount of labor involved that makes you, the reader or spectator, feel spontaneous. Maybe I’m desperately trying to give labor some value, or rigor some value, but I think those are the ones that really inspire you in a moral way, as opposed to something that is just slight or fun. This goes back to why I’m not so crazy about supposed spontaneity in performance art. But it’s hard to tell how tooled O’Hara’s stuff is until you try to do it yourself.

CH: When you look at his collected poems, and you consider the time frame in which he wrote them, it’s such an enormous body of work. He was writing two, three, sometimes four poems a week. He was practicing, training, “working” all the time. Yet you don’t feel, as in a Robert Lowell poem, the beads of sweat on each line. It reminds me of Michael Palmer’s observation about the Lowell/ Plath/Berryman generation, which is that one can feel their thirst for fame in how hard they were trying with every jacked-up line.

DL: Ultimately what we’re talking about is our relationship to labor. It’s not about how much work you do or do not put in, but about how you relate to the work in the first place. It’s about having a reciprocal relationship with your work, where you haven’t become a slave to your work and neither has your work become a slave to you. That’s what characterizes a healthy relationship with work. One of the things I started trying to do with this Bauerntheater or other projects is to take the pressure off: it’s basically theater without a director, because it’s no longer staged. Theater without an event, because you can talk, or come and go as you please. This is one way of relieving the pressure of masterworks, or persuasion, or what have you, and allowing the work to diffuse outward. Yet I love directing and staging, and the only straight theater I’ll still direct is actually highly realistic. I find that a pleasure in itself. That’s really like Flaubert. How far can I vanish, as opposed to how can I make myself more apparent? What’s good about realism, and it’s a huge amount of work, is that you ask: can I tool this so thoroughly, can I so saturate every moment with myself, that I just seem to evaporate and make this thing run autonomously, so that you can’t even see a single gesture? Bauerntheater’s the opposite; no illusion at all. Either way it’s OK. They’re both about vanishing.

CH: Directing itself is almost a kind of conceptual art—the gesture of a conceptual artist. It reminds me too of one of Duchamp’s famous lines, which Marina Abramovi´c talks about: the artist isn’t the only one who should be creative.

DL: I am reminded of my two all-time favorite performance pieces. They really inspired everything I do. The first is this Adrian Piper piece, called The Mythic Being, where she just dressed herself up as a black man in Harvard Square—really as a kind of Afro/glam black man— and no one noticed. And she had a friend who just took pictures of her while she walked around Harvard Square. The performance was entirely unannounced, it wasn’t famous till much later. The second piece is [Vito] Acconci’s Following Piece, where he would just follow people in the street. These are paramount performances. They are utterly without vanity. No one knew they were happening at all. They’re moments of just floating insincerity, absolute quiet insincerity, floating through the world.