Some of us live our adult lives—decades—and never realize what we are the best at doing, or what we loved doing the most, our calling, in other words. Or, if we realize it and can articulate it, we never get around to doing it.

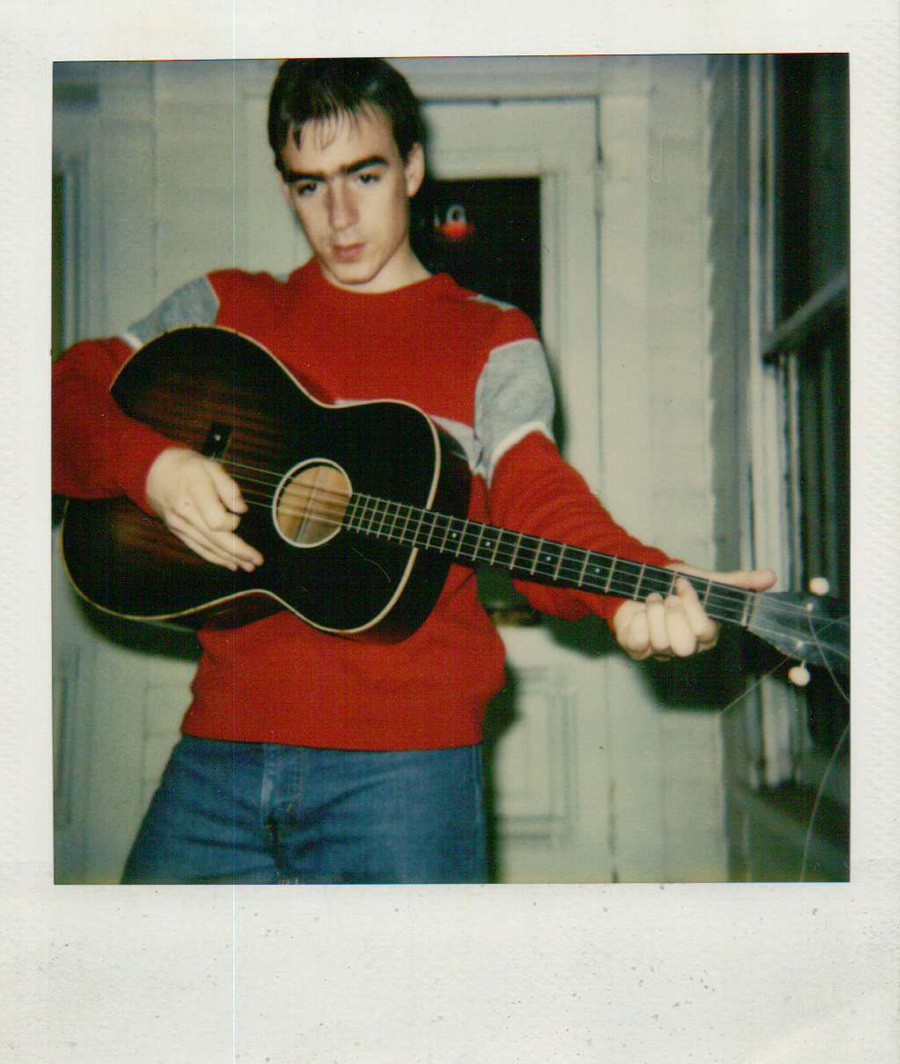

Jason Molina was the opposite of this kind of person. He wrote songs, sang them in unique song structures, and recorded them. By all accounts he applied workaday ethics to song craft from his teens to around age thirty-five, when he succumbed to genetic propensities for depression and substance addictions and proceeded to medicate himself to death before he turned forty.

Molina produced staggering output for two decades, in a variety of settings and musical styles, nearly thirty records, depending on how you count the seven-inch releases, EPs and box sets. He also sent cassette demos to fans that wrote him letters and he handed them out to eager souls in person. He created fresh and original music throughout, influencing musicians such as the Avett Brothers, My Morning Jacket, Waxahatchee, Hiss Golden Messenger, and others, including many in Europe. That’s a good run, a lasting legacy.

Whatever natural talents were Molina’s—a singular vocal sound, for one—were matched by a profound willingness to work, to put in the time to hone the craft he wanted to be good at, and to stick his neck out there, to expose himself trying to do this work at the highest level he could muster. He found his calling and did the work. That’s not tragic.

To borrow a line from Toni Morrison, who grew up in the same Lake Erie steel town, Lorain, Ohio, as Molina, “Beauty was not simply something to behold; it was something one could do,” (her emphasis, from the 1970 novel The Bluest Eye).

In February 2018 I drove six hours to Lorain to visit with Jason Molina’s father, William “Bill” Molina, now age seventy-five and a retired science teacher who logged thirty-five years in the public schools in Lorain, and his sister, six years her brother’s junior, Ashley Molina Lawson, age thirty-eight.

When I arrived in Lorain I had a couple of hours to kill, so I drove to the vacant lakefront lot where Molina, his brother Aaron and sister Ashley had grown up in a trailer park. It was a bitter cold winter day, highs around twenty degrees and twenty mile-per-hour winds coming off the lake. Several inches of snow were on the ground. The Molina’s had the trailer spot on a cliff overlooking the lake. Waves from Lake Erie lapped on the rock jetty in a hypnotic manner, louder than I would have imagined.

Ashley had organized our meeting...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in