If I had to name one book that bewitched me as a child, it would not be a picture book or a collection of fairy tales, but rather a slim, steel blue, clothbound volume on my parents’ bookshelf: a genealogy of my mother’s family dating back to the 1700s. It was, as genealogies tend to be, a network of names, some with biographical entries, others bare, each accompanied by two dates—of birth and death—or, in the case of the latest offshoots, a date, an en dash, and a question mark. I would look for my mother’s name in the book’s final pages and fill in the void that did not contain my father, my brothers, my sister, and me, because the genealogy had been assembled by relatives who had decades earlier settled in San Francisco, and who no doubt (in those pre-internet days) had difficulties tracing all the members of the family, most of whom—including us—lived in the Middle East. Transfixed by the physical orderliness of a no-longer-physical past, and perhaps disconcerted by the fissure the book had inadvertently injected into my family by stripping us of the proof of our existence, I undertook, in childish heroism, my own compendium: a notebook that I titled “Everyone I Have Ever Known,” inside which I wrote, quite literally and in no chronological sequence, the names of everyone I had ever known: family members, friends, teachers, neighbors (both alive and dead). If I understood, even then, the futility of such a project, I could not help the compulsion to contain the uncontainable.

What I did not know was that I had entered Kiš-ian territory, the uncanny terrain of the writer Danilo Kiš.

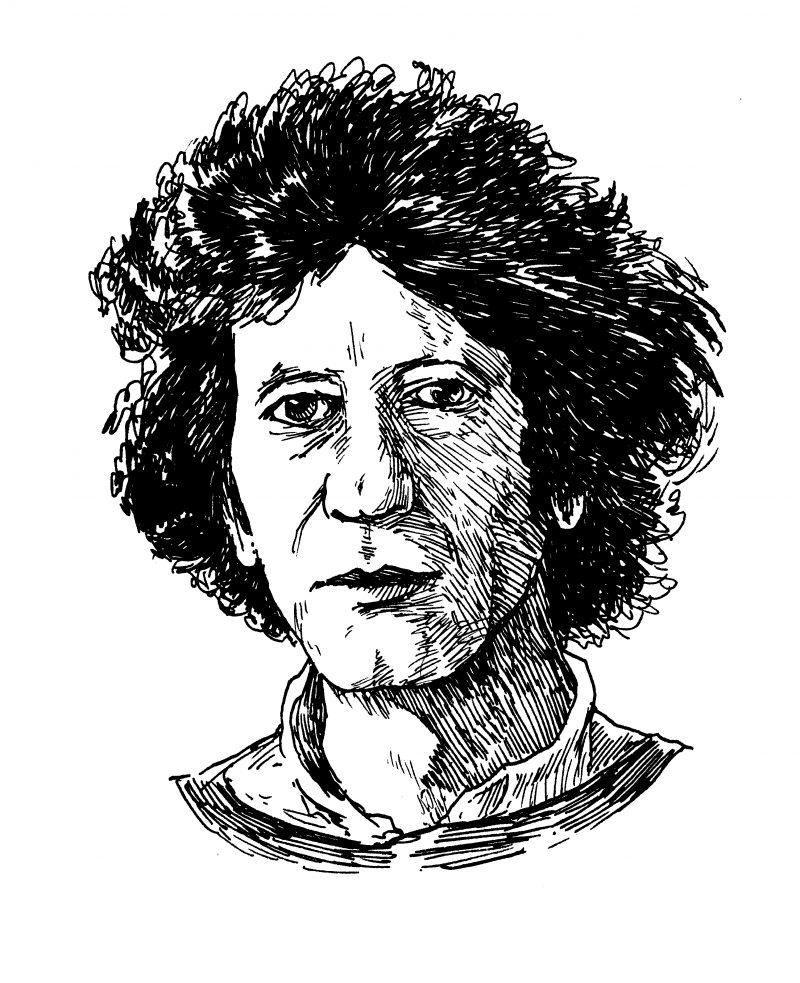

An Orpheus who through mastery of language carries the reader to the underworld and back, Kiš, though still largely unknown in the English-speaking world, was that rare breed of writer as equally committed to style and technique as to excavating the truth, in all its cold-bloodedness—often by reinventing it. As he said in a 1989 interview:

I don’t believe a writer has a right to give in to fantasy… After everything the history of this century has dealt us, it is clear that fantasy, and hence romanticism, has lost all its meaning. Modern history has created such authentic forms of reality that today’s writer has no choice but to give them artistic shape, to “invent” them if need be: that is, to use authentic data as raw material and endow them, through the imagination, with new form.

Hailed by such writers as Susan Sontag, Milan Kundera, Salman Rushdie, and Joseph Brodsky—who deemed Kiš’s novel Garden, Ashes “the best book produced on the Continent in the post-war period”—Kiš was considered for the Nobel Prize in the mid-1980s. As British historian Mark Thompson writes, in a remarkable new biography published in March by Cornell University Press and titled Birth Certificate: The Story of Danilo Kiš: Kiš’s work “carries an echo… of literature seeking a frontier with its opposites: encyclopedias, police files, casualty lists, birth certificates, railway timetables, gazetteers. He tests fiction’s possibilities, not by slighting our desire for stories but rather by drawing that desire into zones of history where it cuts against our hunger for truth, unadorned.”

This knack for walking a tightrope between dual forces and mirror worlds, bordering on necromancy, may be attributed to the fact that Kiš was an inheritor of a perturbed and ultimately miscarried history: he was born in 1935 in Subotica, a former Austro-Hungarian city that had become a Yugoslav border town and would, shortly after Kiš’s untimely death, in 1989, become part of Serbia. His Montenegrin mother was Eastern Orthodox, while his Hungarian father, a railway inspector, was Jewish, a fact that would lead to the family’s multiple displacements during the war and to the father’s eventual deportation, in 1944, to Auschwitz. This disappearance would become the driving force behind much of Kiš’s writings, translations of which have trickled into the United States over the past few decades: most notably A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, introduced by Philip Roth in 1980 as part of the “Writers from the Other Europe” series; the triptych Early Sorrows: For Children and Sensitive Readers; Garden, Ashes; and Hourglass—which together form what Kiš referred to as the “family cycle” books; The Encyclopedia of the Dead; Homo Poeticus: Essays and Interviews; and new translations, last August, of The Attic, Psalm 44, and The Lute and the Scars.

Kiš’s primary subject was persecution, especially the Holocaust and Stalinist purges—historical events he considered too horrific to be presented as either entirely invented tales or wholly realistic fiction. In his family cycle books, he depicted the vanishing world of Hungarian Jews through the disintegration and ultimate disappearance of one Jew: Eduard Scham (based on Kiš’s own father, Eduard Kiš, born Eduard Kohn). Beginning as a peripheral figure in the life of his young son, Andreas (Andi) Scham (Kiš’s fictional doppelgänger) in Early Sorrows, Eduard looms increasingly large in Garden, Ashes, until he reemerges as the central character, E.S., in Hourglass, a mosaic tale of a man writing a letter over the course of a single night, told through four narratives, and elucidated in the final section by an actual (though perhaps somewhat altered) letter that Kiš’s father wrote in 1942 to his sister Olga.

Danilo believed that his father’s vanishing was foretold by his repeated earlier disappearances: diagnosed with “anxiety neurosis,” Eduard Kiš, much like Eduard Scham, was thrice hospitalized, and after the family left Yugoslavia in 1942 to move in with Eduard’s relatives in the Hungarian town of Kerkabarabás, he frequently slipped away from the house to meander through the surrounding forests or to get drunk at one of the village bars. These absences—culminating in his final disappearance—turned the father into something of a myth, thus reversing the order of things: instead of the son growing up to vanquish and eventually reconcile with the father, the vanished father consumed the son, perhaps leaving no possibility for reconciliation. “I had not previously been in a position to observe my father,” Andi says in Garden, Ashes, “and my curiosity in this respect had been completely frustrated by his repeated absences, by what I would call his conscious sabotage of my Oedipal curiosity.”

As Thompson explains, the writings Eduard Kiš left behind—a collection of personal papers and documents, along with the 1938 edition of The Yugoslav National and International Travel Guide, which he had edited—would become springboards from which Kiš reconstituted his father. In a fictional account of their departure from Kerkabarabás after the father’s disappearance, Kiš writes: “Here are his birth certificate, his school diploma, those incredible torahs covered with the script of a distant, almost mythical past, precious testimony of a dead poet… this would be the sole legacy of my childhood, the only material proof that I ever existed and my father ever existed.”

*

Grappling as he did throughout his life with his father’s vanishing, Kiš was all the more wary of nationalistic expressions such as “fatherland,” and leaders proclaimed to be “spiritual fathers” of a nation. “Kiš knew all about fake fatherhood and its political dangers,” Thompson writes. “The stories in A Tomb for Boris Davidovich circle like planets around a dark sun, named only as ‘the Father of the people.’”

Consisting of seven stories, all of which, except one, have to do with Stalin’s Great Terror in the late 1930s, A Tomb for Boris Davidovich weaves in characters both real and invented whose doomed fates are based on historical truth. (The one story not concerned with the Great Terror has to do with the Jewish pogroms in fourteenth-century southern France.) Kiš described the basis of this book as “facts in literary form” or “narrative facts.” In the title story, the anonymous narrator wonders whether history has “recorded” Boris Davidovich Novsky, since he “appears in the revolutionary chronicles as a character without a face or a voice.” Through references to found documents and letters (some written as parodies of the ornamental and sentimentalist style of some of Kiš’s Yugoslavian contemporaries, many of whom were his critics and detractors), we learn that Novsky, a Jew, was several times imprisoned for his revolutionary activities against the czar, and that after the revolution and a brief marriage, he was imprisoned and tortured by the communists. Novsky escaped from prison, and after being pursued for three days, he leaped from a ladder into a furnace, rising “like a wisp of smoke, deaf to their commands, defiant, free from German shepherds, from cold, from heat, from punishment, and from remorse.” He left behind “a few cigarettes and a toothbrush.”

The desire to unearth one man’s life from the archives of humanity is likewise fully present in “The Encyclopedia of the Dead,” a short story translated into English and published in the New Yorker in 1982, and again in 1989 as the title story of a posthumous short-story collection. In this story a woman grieving the death of her father dreams of a library that houses the Encyclopedia of the Dead, a book that records everything that can be recorded about those who led ordinary lives and who are therefore not written about elsewhere. There she finds an entry on her father and learns every detail about his life, each given equal significance: “And here is my father as a young man, his first hat, his first carriage ride, at dawn. Here are the names of girls, the words of the songs sung at the time, the text of a love letter, the newspapers read—his entire youth compressed into a single paragraph.” She goes on: “It is 1928; the young man… has grown a moustache. (He will have it for the rest of his life. Once, fairly recently, his razor slipped and he shaved it off completely. When I saw him, I burst into tears: he was somebody else. In my tears there was a vague, fleeting realization of how much I would miss him when he died.)” The narrator reads on, eventually finding the “floral patterns” her father had begun painting around the house in his later years, and discovers a flower described in its caption as “the basic floral pattern” of her father’s drawings. She begins copying it: “It resembled a gigantic peeled and cloven orange, crisscrossed with fine red lines like capillaries.” The final paragraph of the encyclopedia entry informs her that her father took up painting “at the time the first symptoms of cancer appeared. And that therefore his obsession with floral patterns coincided with the progress of the disease.” Later, awakened with terror from the dream, she draws the flower and shows it to her father’s doctor, who “confirmed, with some surprise, that it looked exactly like the sarcoma in my father’s intestine. And that the efflorescence had doubtless gone on for years.”

*

Apparent throughout Kiš’s work are doubles, mirroring images, and antipodal notions. “Dissimilarity was Kiš’s favorite word to explain his multiple, unresolved identities,” writes Thompson. “If not for the ambiguity of my origins,” Kiš said in a 1986 interview, “if not for the ‘troubling strangeness’ created by my being Jewish, if not for the hardships of a wartime childhood, I’d never have become a writer.” It must be noted, however, that Kiš never wrote of Jewishness as a form of allegiance, but rather to portray a metaphysical state: Jewishness as a condition that’s inherited—in other words, the exploration of being a Jew in the world, carrying within one’s body and psyche the collective memory of Jews past. In Garden, Ashes, after the family moves into a decrepit bungalow, young Andi begins having headaches and indigestion. “Only later,” he says, “did we realize that my diarrhea was the consequence of fear, which I had likewise inherited from my father.” Andi takes to reading the Small School Bible, and plays all the various biblical roles. When he takes on the role of Moses, he says: “I experience what is surely the strangest of my metamorphoses, a quasi-anthropomorphic flashback to my earliest childhood. Of course, I once more become a victim, the most innocent victim in the world, victim of victims (like my father): one of the male children of Israel thrown into the waters of the Nile… As always, however, I am the shining exception, the mortal who will evade death…” The “quasi-anthropomorphic” metamorphosis brings to mind Kafka’s Gregor Samsa, the traveling salesman (not unlike Andi’s father, who is “the genius of travel” and whom Andi calls “the Wandering Jew”) who gains self-awareness only after he is transformed into an insect.

One of Kiš’s preoccupations was the uncanny, which Thompson sums up as “the moment when an object changes meaning so completely that it might be a different thing—when it becomes its own double.”

“It is difficult, impossible even, to separate the autobiographical element from a work,” Kiš said in a 1973 interview. “I tried to justify the duality, find an alibi for it, in the opening chapters [of Hourglass]. Hence, for instance, the image of the hourglass with its two facing profiles (a symbol of the creative principle)… To put it more precisely: the existence of documents bearing on my father obliged me to be faithful to them, just as the existence of his letter (which closes the novel) kept me from speaking of things not in it—or at least not touched upon, hinted at, inherent in it.”

In Garden, Ashes, Andi’s doubling begins the moment his mother tells him that his uncle is dead. “This new and shocking foreknowledge of mortality,” writes Thompson, “means that Andi has crossed a threshold—the one that leads to Rilke’s Doppelbereich, the ‘double realm’ of which we all become subjects.” And with this new awareness he begins seeing his body as a mirror image of himself: “I couldn’t imagine how one day my hand would die, how my eyes would die… I had suddenly come to understand that I was a boy by the name of Andreas Scham, called Andi by my mother, that I was the only one with that particular name, with that nose, with that taste of honey and cod-liver oil in his mouth, the only one in the world whose uncle had died of tuberculosis the previous day, the only boy who had a sister named Anna and a father named Eduard Scham, the only one in the world who was thinking at that particular moment that he was the only boy named Andreas Scham, whom his mother called by the pet name Andi.” This spiraling mind game reminds him of “a tube of toothpaste that my sister had bought a few days earlier, on which there was a picture of a young lady smiling and holding a tube on which a young lady was smiling and holding a tube… The mirror game tormented and exhausted me.” Andi thus begins his obsession with mortality, and comes to think of the word death as the “divine seed” that his mother had “sowed” in his curiosity. And so it is the mother, giver of life, who sows inside her son the seed of death. Unable to sleep at night, he begins counting, but the numbers only remind him of “the number of years left in my mother’s life.” And since each number only leads to the next one, he gets lost in “eternity’s abyss”—and again we are led to infinite mirrors leading to death.

In a terrifying passage in Hourglass, E.S. experiences a complete dissociation from his self while shaving: “On one side E.S., fifty-three, married, father of two children, who thinks, smokes, works, writes, shaves with a safety razor, and on the other side, next to him, or rather inside him, somewhere in the center of his brain, as though asleep or half asleep, another E.S., who is and is not I… shrunk to the size of an embryo, is doing something entirely different, engaged in unknown and dangerous occupations.” (We have, once more, in the word embryo, an echo of the “divine seed.”) This schism culminates in a majestic metaphor at the end of the novel, when E.S., cognizant of his approaching death, says:

Let my body be my ark and my death a long floating on the waves of eternity. A nothing amid nothingness. What defense have I against nothingness but this ark in which I have tried to gather everything that was dear to me, people, birds, animals, and plants, everything that I carry in my eye and in my heart, in the triple-decked ark of my body and soul… I have wanted and still want to depart this life with specimens of people, flora and fauna, to lodge them all in my heart as in an ark, to shut them up behind my eyelids when they close for the last time.

The metaphor of Noah’s ark, which in Garden, Ashes Andi describes as his “personal drama” (will there be a place for him on the ark or will he drown?), overtakes E.S.’s body in Hourglass, becoming, as E.S. says, “a bitter poetic metaphor” that he carries “with passionate logic to its ultimate consequence.”

*

Here are Kiš’s other preoccupations: the need to know everything there is to know about a single life; the uncanny experience of encountering doubles (the father without a mustache becomes “somebody else,” a forewarning of his death); and the dangers of knowing too much: the floral pattern, discovered by the narrator in a dream, makes her confront what her father had foreknown (and that she, too, had foreknown, since she dreamed it): the tumoral shape of his death. “Knowledge promises to restore to her something more complete than what she has lost, and so she reads on,” writes Julia Creet in her essay “The Archive and the Uncanny: Danilo Kiš’s ‘Encyclopedia of the Dead’ and the Fantasy of Hypermnesia,” published in Lost in the Archives, Alphabet City, # 8. “Yet, in the process of reading on she is drawn further and further towards her own death, towards the time before she was and towards the entry that will be hers… Rather than accept the incompleteness of the historical record, and acquiesce to the loss of memory that accompanies this kind of mass destruction, Kiš, in his Encyclopedia, fills in all the gaps, exhuming the uncanny nightmare of the living that both fears and longs for a complete record of the dead.”

The yearning for a complete record is echoed in Garden, Ashes, in the father’s mad compilation of a new edition of the railway timetable, which, begun as a routine updating of its earlier version, grows unchecked into a tentacled manuscript that strives to include “all cities, all land areas and all the seas, all the skies, all climates, all meridians… This was an apocryphal, sacral bible in which the miracle of genesis was repeated, yet in which all divine injustices and the impotence of man were rectified… With the blind rage of a Prometheus and a demiurge, my father refused to acknowledge the distance between earth and heaven.” Eduard Scham’s sprawling, ever-multiplying manuscript remains unpublished, only adding to his rage and despair. (The compulsion to catalog the universe brings to mind Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, in which Judge Holden, the leader of a gang of Indian scalpers and a figure reminiscent of Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost, draws every specimen he encounters in a notebook, because, as he says, “Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent… Only nature can enslave man and only when the existence of each last entity is routed out and made to stand naked before him will he be properly suzerain of the earth.” McCarthy’s judge is persecutor while Kiš’s Eduard Scham is persecuted, but they represent mirroring reflections of the same urge to contain the world and not be contained by it.)

What is behind the urge to archive the universe in its entirety? We live increasingly in an age of archives: of recorded testimonials, intimate memoirs, and personal documents and photographs backed up on hard drives—those boundless repositories of “memory,” which, when filled to capacity, can simply be supplanted with additional “memory space.”

When a society loses its inherent memory, writes French Jewish historian Pierre Nora in Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire, which “takes root in the concrete, in spaces, gestures, images, and objects,” it starts relying on external markers.

Modern memory is, above all, archival… Museums, archives, cemeteries, festivals, anniversaries, treaties, depositions, monuments, sanctuaries, fraternal orders—these are the boundary stones of another age, illusions of eternity. It is the nostalgic dimension of these devotional institutions that makes them seem beleaguered and cold—they mark the rituals of a society without ritual.

By using actual and imaginary documents, Kiš, from the frozen and archival repositories of memory, resurrects individuals and restores to them their lost dignity. Rather than becoming an archivist, he salvages individual lives from the vaults of the archives. It is interesting to note that in his essay “Advice to a Young Writer,” he included: “Do not write for holidays and anniversaries,” and “Do not write funeral orations for national heroes: you will regret it.”

*

Kiš’s consummate exploration of persecution and memory makes him an important writer, but what makes him an exceptional one is the luminosity of his prose and the virtuosity of his technique. To eschew mimetic realism without slipping into pure abstraction, he tirelessly pursued what he referred to as “the grace of form.” But while he admired a pure stylist like Nabokov, he did not agree with Nabokov’s assertion that a work of art should be concerned only with aesthetics and not at all with the affairs of the real world. “With a pleasure which is both sensual and intellectual,” Nabokov wrote in his essay “Good Readers and Good Writers,” “we shall watch the artist build his castle of cards and watch the castle of cards become a castle of beautiful steel and glass.” If Nabokov aspired to books of “steel and glass,” Kiš sought to seize in his writings extinguishing oil lamps and surviving scraps of paper. “Being a witness does not preclude literary mastery,” Kiš wrote in a 1986 essay titled “Nabokov, or Nostalgia.” He continued: “For Nabokov… history was the illusion of an illusion. And if he overlooked the crucial fact of the twentieth century—the camps—and rejected them as material unworthy of his pen, it was not only because he did not wish to waste his life in vain polemics but also because he placed his bet on eternity rather than on the moment.” This divergence between Nabokov’s insistence on style free of worldly concerns and Kiš’s determination to illuminate worldly concerns through style may be attributed to the two men’s antipodal childhoods: Nabokov’s idyllic boyhood of countesses and butterflies in pre-Bolshevik Russia versus Kiš’s nightmarish world of assassinations and vanishings, first in Yugoslavia (where his father was nearly killed in a 1942 massacre in Novi Sad) and later in Hungary, where the family stayed with Eduard Kiš’s Jewish relatives, most of whom eventually disappeared along with his father.

Despite these differences, Kiš, like Nabokov, was recognized as a literary descendant of James Joyce, and he said on numerous occasions that he could not have written Hourglass without having first read Joyce. But as Thompson explains, Kiš’s connection to Joyce extended beyond the stylistic: “For agnostic Bloom as for gnostic Kiš, the loss of the father created the only felt ties to Judaism—ties of remorse in Bloom’s case, and in Kiš’s, of filial loyalty and a quest for origins. Bloom preserves his father’s Haggadah and suicide note. Kiš kept the sheaf of documents that his father left behind.”

Kiš also found kinship with the writings of Jorge Luis Borges. “Liberation from psychological clichés—this is what Borges means above all,” he said. “As well as that,” writes Thompson, “[Borges’s] intertextuality (allusion to other literature), his use of real and fictional documents, playful erudition (invented bibliographies, quotations from non-existent works), compression, rigor, witty intelligence, detachment, eclecticism, veneration for European literature, mockery of national conceptions of literature, wonderful narrative clarity and drive: these all appealed immensely.” Kiš’s other “conversation partners” (a term a French interviewer once used and which Kiš highly preferred to the more common “literary influences”) included Rabelais, Proust, Kafka, Schulz, as well as the Yugoslav writers Ivo Andrić, Miroslav Krleža, and Miloš Crnjanski.

Kiš’s brilliance lies in his transformation of history, through language, into a transcendent experience. Consider the habit of Eduard Scham of blowing his nose into scraps of newspaper:

He would cut up the pages of the Neues Tageblatt into four parts and keep the sheets in the outside pocket of his frock coat. Then he would pause suddenly in the middle of a field or in the woods, rest his cane on his left arm, and blow his nose like a hunting horn. First a vigorous blow, then two weaker ones. You could hear him, especially in the woods, at sunset, a mile away. Then he would fold this scrap of rather heretical newspaper and toss it to his right.

Young Andi, when walking through the forest, would sometimes come upon these scraps and think: “My father was wandering along here not long ago.”

Here again is the Wandering Jew, the sound of the blowing of his nose reminiscent of the call of the shofar, the ram’s horn traditionally blown in three sequences in synagogues as a wake-up call from spiritual slumber. Andi continues: “Two years after his departure, when it was clear to us that he would never return, I found one of these faded scraps of newspaper in a clearing in the Count’s forest, amidst the grass and cornflowers, and I told my sister Anna: ‘Look, this is all that’s left of our father.’”

“Never the most characteristic writer from Yugoslavia, [Kiš] became the most essential,” Thompson writes. Highly wary of literature that pledged allegiance to one group or another (be it nationalistic, religious, or cultural), Kiš maintained throughout his life his individuality as a writer. In “The Short Biography of A. A. Darmolatov,” the final story in A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, which Kiš later defined as “a fable and as such the moral of the entire work,” hackneyed poet Darmolatov, closely aligned with the state, develops elephantiasis at the end of his life. “A photograph of his scrotum,” says the story’s narrator in a postscript, “the size of the biggest collective farm pumpkin, is also reprinted in foreign medical books, whenever elephantiasis (elephantiasis nostras) is mentioned, and as a moral for writers that to write one must have more than big balls.” Kiš commented on this metaphor in his essay “Individuality”:

[In Yugoslavia], when we say a writer “has balls,” we also mean he has a God-given talent, he is a literary stud horse, a lyrical centaur… with nothing but his spermatozoal instinct to guide him, yet declaring all other motion in space and time with its own direction, its own logical conception of mind and spirit, to be suspect erudition, Western influence, decadent and Cartesian… Balls thus serve as a guarantee that the artist will not infringe upon the laws of the community in word, thought, or deed.

*

For this steadfast defense of a writer’s independence of mind, Kiš paid a high price: after the publication of A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, he was accused of plagiarism by the Yugoslav Union of Writers, which, unable to overtly fault him for his veiled criticism of the Comintern in Yugoslavia, chose instead to attack him on literary grounds. (It claimed that his literary allusions constituted plagiarism.) Kiš retorted with a book entitled The Anatomy Lesson, in which he proclaimed nationalism to be “first and foremost paranoia, individual and collective paranoia,” and “the ideology of banality,” a “totalitarian ideology.” He continued, “All writers who proclaim they are writing ‘of the people and for the people’ and claim to subordinate their own voices to the superior interests of the nation are suspect.”

No doubt Kiš would appreciate this ultimate irony: that his face now appears on Serbian postage stamps as part of the “Great Personalities of Serbian Literature” series issued in 2010. The writer who during his life resisted nationalism at all costs and resurrected forgotten men from official archives has been appropriated by the state after his own death, and turned into an official trademark.

But while a postage stamp may seem like a defilement of Kiš’s legacy, Thompson’s biography is a great tribute: echoing Kiš’s quest for the “grace of form,” it is not only comprehensive and literary but also innovative in its technique: each section is a commentary on a short autobiographical text written by Kiš, called “Birth Certificate.” It is interesting to note that Thompson titled his biography Birth Certificate: The Story of Danilo Kiš (and not “The Life of Danilo Kiš”). Why “story”? Perhaps because professing that something is an account of a “life”—as many biographies do—would be to tumble into the very pitfall that ensnares the narrator of “The Encyclopedia of the Dead.” The word story, then, is more appropriate, as it presents the reconstituted narrative of a writer who once wrote, “If you cannot say the truth, say nothing.”

It is this encounter with the truth, in all its reshaped reflections, that makes Kiš’s writing so exhilarating: mirrors inside mirrors inside mirrors, leading the reader into infinitesimal depths of being—and nonbeing. It is, as well, his ability to resurrect the dead from historical archives, his compulsion to catalog the universe with dizzying—and dazzling—lists, and, perhaps most important, his remarkable skill in exploring his own devastating loss not through a mimetic reconstruction of the past but through deflection, refraction, and reinvention.

One of the most chilling passages in Garden, Ashes is that of Eduard Scham’s arrest while he is napping in the forest. A double-barreled shotgun is placed at the small of his back, making him sit up and surrender. It is at that moment that young Andi merges with his father, for the “I” of the narrator suddenly becomes “we”: “A woodpecker was drumming away over our heads: tap-tap-tap, tip tip-tip, tap-tap-tap, tiptiptiptip—it could be interpreted as a bad omen. My father had the same thought, for he turned his head in that direction cautiously, as if deciphering a message in Morse code.” Andi at that moment enters his father’s head (“My father had the same thought”), and we know that the consumption of the son by the soon-to-be-vanished father is now complete. And as Eduard Scham, a one-time railway employee who is familiar with Morse code, decrypts the news of his own death as delivered by the woodpecker, so does Andi, who, having merged with his father, will from that moment on look for clues, codes, and patterns in order to make sense of an otherwise senseless existence.

This passage hooked me on Kiš because it captured, with that “dissimilarity” characteristic of Kiš, something I had already understood but feared: when my own father disappeared one afternoon in Tehran in 1980, I was convinced that the void in my mother’s genealogy book had been confirmed. My father returned, but the void, now having been tampered with by fate, became for me a looming nonbeing. As I recognized decades later while reading Kiš, the vanishing had been foretold.