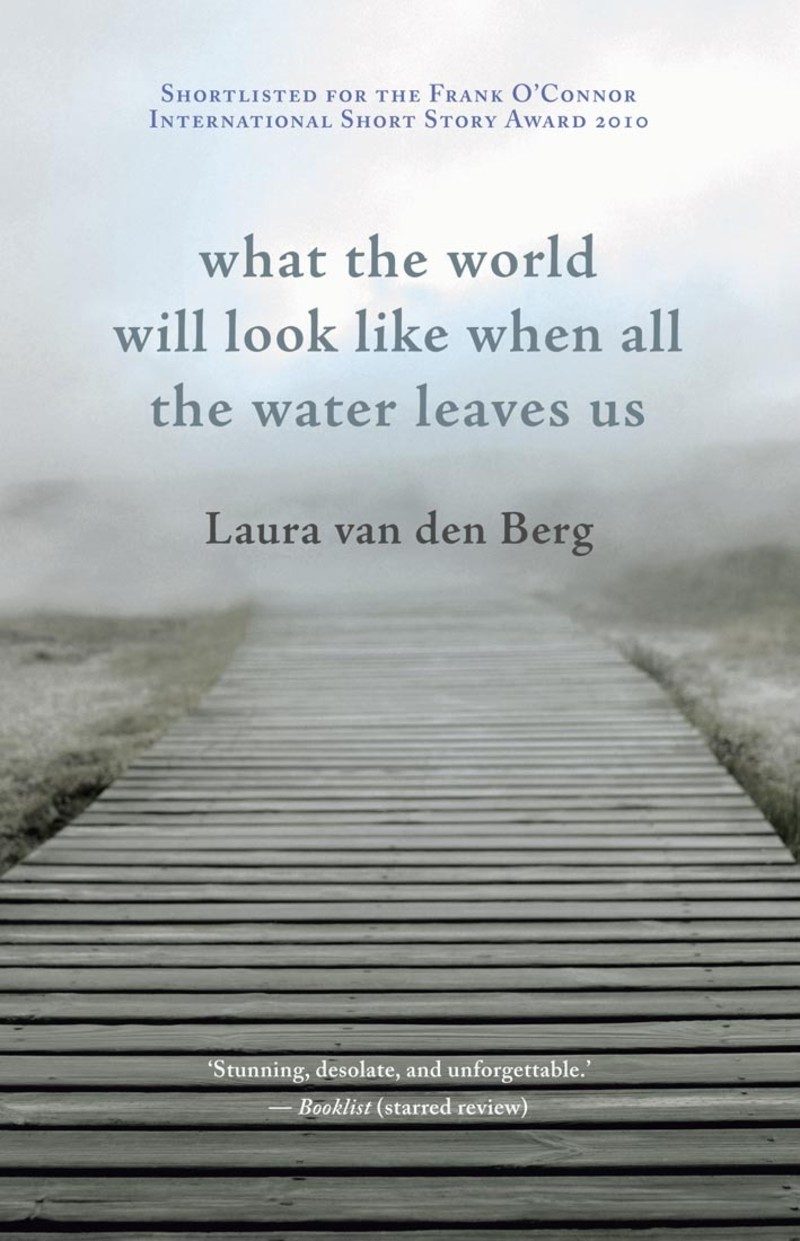

1. Mythical/Elusive/Almost-Extinct Creatures

Throughout the pages of this story collection, strange beasts lurk in jungles and lakes and minds: shadowy, sought-after, difficult to catch. On the actual-to-mythical spectrum, these creatures fall between real (lemurs in Madagascar, the mapinguary in the Amazon) and believed to be real (the Loch Ness monster, the Congo’s river-stopping sasquatch known as the mokele-mbembe, a giant Lake Michigan water snake called mishegenabeg). A woman channels Bigfoot, “lumbering through the forest, more alone than any human could grasp,” because when she’s in bestial character, “everything real about my life blacks out.” She’s not the only one who craves escape: characters pursue legends and rare specimens in attempts to flee their own tangled realities. This cast of creatures helps the stories explore what we believe, what we fear, and how we try to “bridge the unbridgeable.”

2. Searching and Exploring

Small- and large-scale expeditions yield varying levels of success. But even fruitless pursuits are not meaningless.A young man frequents a bookstore looking for a first edition of Moby-Dick, the consummate watery quest. The scientists, explorers, little brothers, and wandering women who people these stories are all on the hunt, be it for a dwindling species of Twinflower or the root causes of misunderstandings. “You can’t fear what you seek,” a Loch Ness explorer explains.And that is a recurring challenge for these characters: reaching a point where what they’re looking for no longer frightens them. “Laugh if you want,” a husband says to his wife about his search for the mishegenabeg,“but I finally know what I’m looking for.”

3. Disappearances and Transformations

In a phone message, a husband tells his wife he’s gone and not to look for him. Another husband is lost in a house fire. A father drowns. Parents get bitten by a poisonous snake and die in “a land of treachery and mystery.” The ones left behind dream of vanishing under water, in foreign lands, behind huge and frightening masks. But there’s a difference between disappearing and changing into something else, and the focus here is on the process of the unfamiliar becoming familiar (and vice versa): “I realize I can’t follow regular conversations anymore,” one narrator notes,“as though the life Susannah describes is now as foreign to me as monsoons and jungles and legends of monsters once were.”

4. Water

Water proves both a comfort and a source of dread, from a woman’s sound machine with settings for “Roaring River” and “Midnight Mist,” to ponds, fogs, and the dark expanse of the ocean. Characters edge against the temptation to permanently immerse themselves; some find they “just needed to duck underneath the surface long enough to figure a few things out.” The urge is one of surrender. These stories nail the distinction—sometimes only just detectable—between fear and the exuberance of release. “All bodies of water look the same to me now,” one narrator observes.“Places to get lost in.” These characters lose themselves, intentionally and otherwise, but they’ve got the courage to go about finding themselves, or changed versions of themselves, in elegant processes of drowning, cleansing, and rebirth.