Thomas Y. Levin is a professor of German at Princeton University. During the week, he lectures on Weimar cinema and the Frankfurt School. On weekends, he sometimes goes to flea markets. His preferred spot is west of campus, in the old mill town of Lambertville, New Jersey, and it is known locally as the Golden Nugget. Every Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday for the past fifty-three years, hundreds of vendors have set up tables on a seven-acre lot by the banks of the Delaware River and laid out the week’s assortment of cast iron, coins, and midcentury decor. Levin, a media theorist and cultural materialist, appreciates the landscape of commonplace objects. “It provides a marvelous overview of the bizarre detritus of daily life,” he says. “The flea market is the unconscious of the recent past.”

Some years ago, Levin was browsing the Golden Nugget when he came across a strange item. The object was a blue mailing envelope about six inches square. In the upper right corner was an image of an airplane. In the bottom left, a battleship. The envelope was addressed to Mr. and Mrs. F. G. Lewis of Louisville, Kentucky, from Private C. W. Lewis of San Diego. A merry midcentury script sang out: “Letter on a Record.” Levin poked a finger inside and extracted a cardboard disk. The disk was coated in shellac and was cut with a spiraling groove.

When a professor of media studies finds a strange cardboard disk at a flea market, he wants to play it. Levin took the record home and placed it on his turntable. The record emitted a low, sizzling rush that rose and fell, like the rhythmic thumping of windshield wipers. A tinny, percussive voice came through.

The open window, it said. Beautiful bedroom. Really beautiful.

The voice was faint and remote. Phrases came up half-swallowed, then dropped away, as if carried by the wind. The speaker said he was in San Diego. He wasn’t doing much. He had been looking for Carl, but Carl wasn’t around.

Well, Mother and Dad, he said, I guess you’re listening in too. But don’t keep your ears too open. I may say some things you may not appreciate.

The “Letter on a Record” was exactly that. Sometime in the early 1940s, Private C. W. Lewis had recorded a message and sent it through the mail. What Levin had found, in other words, was voice mail.

Most people think of voice mail as a relatively recent technology. It was only in 1984 that the answering machine reached a wide audience with AT&T’s Telephone Answerer, a chrome-and-faux-wood-grain apparatus that recorded up to 120 voice messages on magnetic tape. Soon the answering machine was a fixture in the American home and a common pop-cultural trope. Movie plots turned on the ill-timed voicemail, while sitcom characters from Ross Geller to George Costanza signaled jadedness or wit with a novelty outgoing message. A generation of on-screen men used the answering machine (and the woman on the other end who wouldn’t pick up) to make their inner speech external. Voice mail was a charming chapter in media history, but like all good things, it did not last. Voice calls are on the decline these days, and text is supreme. The modern voice mail in-box is no more than a graveyard for robots, scammers, old folks, and dental offices.

From our contemporary vantage point, voice mail may seem like a quaint artifact of the ’80s and ’90s. But the answering machine was in fact preceded by a lesser-known era of voice messaging, one which began in the early 1900s and grew out of the phonograph. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, and before he unveiled the device to the public, he spent some time colliding morphemes in a notebook. He thought he might call his invention the “antiphone” (back-talker) or the “liguphone” (clear speaker), or perhaps the “bittakophone” (parrot speaker), “hemerologophone” (speaking almanac), or “trematophone” (sound borer). In the end, Edison settled on the straightforward “phonograph,” meaning “sound writer”—an efficient summary of its mechanism. The phonograph received vibrations from the air and transcribed them as calligraphy. Sound waves would cause a needle to quiver, and the needle would etch a continuous line on a turning cylinder. If you reversed the process, the needle would travel along the groove, mining sound from the uneven topography and playing it back through a horn.

Every invention is invented twice, first by its creator and again by its users, who decide what the item is really for. By the 1910s, the phonograph had become popular as a music player, but this had not been Edison’s intent. As his early ideas for names suggest, he was more interested in creating a machine that would talk. He envisioned the phonograph as a device for the office or the classroom: a memo writer, a dictation machine, a mechanical tutor. Others saw the same potential. When the phonograph was still in the murky phase of its identity, certain companies suggested that it might be used for auditory epistles. One such company was Speak-O-Phone of New York, which in 1928 introduced an accessory that allowed families to make personal recordings at home. Solomon Popper, the company’s chief executive, described the technology as “instant photography of the voice on a record,” and suggested that such records could be sent through the mail.

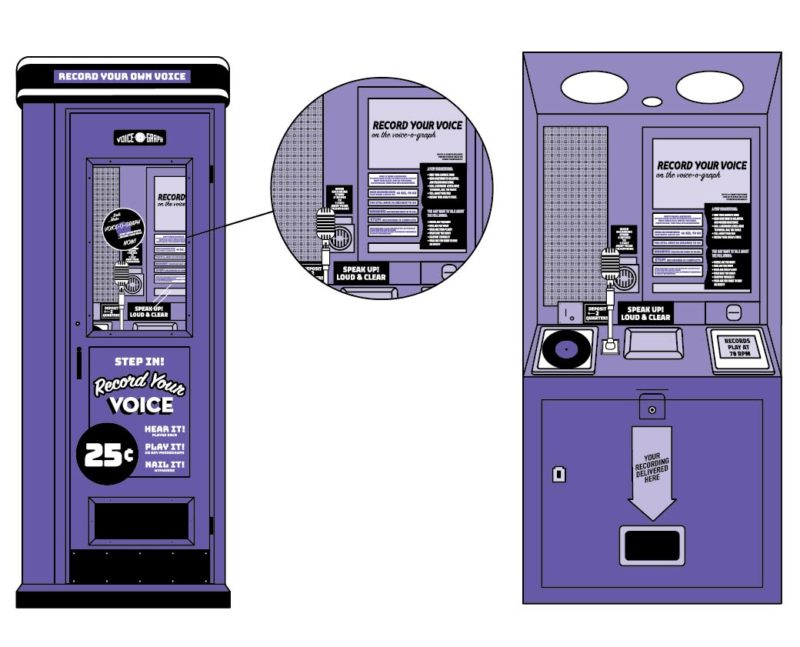

Popper’s invocation of photography was prescient. Around the same time, a New York–based arcade games manufacturer called the International Mutoscope Corporation had debuted the Photomatic, the first boardwalk photo booth, which developed one’s portrait in less than a minute using a chemical bath built right into the cabinet. In light of the Photomatic’s success, Mutoscope came up with another machine based on a similar principle. This device was the Voice-O-Graph. Like the Photomatic, the Voice-O-Graph consisted of a small booth with a door, but instead of a camera it housed a microphone. If you deposited a coin, a light would turn on and a timer would start. For about a minute, you were free to speak. When the time had elapsed, your recording would play back, then it dropped into a slot, along with an envelope. There was your voice as physical fact, ready to send through the mail.

Voice-O-Graph booths dotted the country for a period of about thirty years. You would find them in America’s great heterotopias, in bus stations, at tourist attractions, and on boardwalks, among other sites of passing through. There was a Voice-O-Graph booth at Coney Island, and another on Attu Island, Alaska. There was one on the eighty-sixth-floor observation deck of the Empire State Building, next to a pair of coin-operated binoculars. The binoculars invited visitors to survey the skyline; the Voice-O-Graph asked them to describe it.

It is not so unusual to hear someone from the past speak to us across the wide gulf of time. We have old radio broadcasts, film archives, and I Love Lucy. We are generally undisturbed by the voices of the dead. But when Levin played the “Letter on a Record” on his turntable in Princeton, New Jersey, he found that it had a different quality—one of intimacy, privacy. He felt as though he were eavesdropping. Private Lewis was a regular citizen addressing his family, and his concerns were ordinary, even boring. The message’s tedium was precisely what made it riveting. Here was a person from the past, in his own little life, speaking off-script and sounding exactly as he had sounded.

Levin wanted to find more records like it. He checked the catalogs at the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum, but they had only a few. Levin wondered where the rest had gone. It seemed that in his passage through the flea market’s open waters, he had spied a white seabird, and just as seabirds alert sailors to the existence of land, the little record in an envelope had disclosed an island of media history that remained unmapped.

Levin is an enthusiastic man with curly silver hair, clear eyes, and a resting expression that makes him look somewhat electrocuted. When he gets going on this or that, his eyebrows and his voice climb in tandem. He is the child of European Jews who fled fascism and grew up speaking German. Levin speaks one word at a time, with the over-enunciated propriety of someone who knows many languages. This is no affect; he knows four.

In the years since his Lambertville find, Levin has been assembling the world’s only archive of gramophone epistles. His archive is located in his faculty office at Princeton. When I paid him a visit last spring, I circled the German Department until I arrived at his closed door. On the other side was an office stuffed to capacity. There were archival boxes from the floor to the ceiling. A small, conical gramophone horn sat upside down on a table, like a dunce cap. There were other strange and obsolete devices. One shelf displayed a collection of toys, among them a Playmobil TSA security checkpoint, a Playmobil surveillance van, and a 2010 Barbie Video Girl, whose locket conceals the lens of a working camera. The titles on his bookcase included Isaac Asimov’s Futuredays, Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, and several editions of 1984. As my eye drifted up the shelf, I spied, at the very top, the black drum of a zoetrope.

“You are wearing a jacket!” Levin said to me. “Why?” The reason, he explained, answering his own question, was that he had received special permission from building services to override the thermostat. He now kept his office at a humid sixty-nine degrees Fahrenheit, the ideal archival temperature. Along the wall were enormous metal filing cabinets, and inside were folders as thick as textbooks. The tabs read

EMPIRE STATE OBS, CONEY ISLAND, AMUSEMENT PARKS, SWITZERLAND, LUXEMBOURG, POLAND, PORTUGAL, BRAZIL, TAIWAN.

Each folder was full of records.

Levin has more than three thousand records in his archive, many of them acquired on eBay. Just that morning, he had received a package from a seller.

“Let’s listen to one of these,” he said, and opened it. He placed the record on a turntable.

The record emitted a loud rushing sound. Beneath the white noise, a man and a woman talked over each other. I rode on a roller coaster! the man said, laughing. What can I say? said the woman. Oh, it’s all over now!

Levin interjected. “The term for that is self-conscious silliness under media duress.” Self-conscious silliness under media duress might also describe sticking out one’s tongue behind a Snapchat filter or dabbing on the Jumbotron.

Levin removed the record from the turntable and placed it in a clear Mylar sleeve. He had consulted with a specialist at the Library of Congress for advice on long-term storage. “Chemically inert, they’re beautifully transparent,” he said. “I am a fetishist.”

We listened to a few more records. Buzz spoke to Mary: We’re just loafing around as usual and decided to make use of this little gadget that they have here. I thought you could get a better idea of my voice this way than if I described it to you by mail. One good thing about a recording, you see, is if you don’t like it, you can turn the durn thing off.

On another record, a baby was babbling. On another, a man spoke to a woman in Japan. Baby, Keiko, honey, I—I want to see you real bad. I—it really hurts me to be away from you like I am. I—at night, I—I can’t sleep, I dream about you. I—I say your name in my sleep…

Some may wonder how it is possible to collect something that everyone, including the Library of Congress, has forgotten about. Levin credits his “incredibly honed online search skills.” At least once a day, he visits eBay US, eBay UK, eBay Canada, eBay France, eBay Germany, eBay Italy, and eBay Brazil. When he first began collecting, he bid as the average civilian does. He would join an auction just before it finished in order to pounce in the final minute. This often required setting alarm clocks for the middle of the night. Now he uses a bot called Gixen to “avoid temporal suck.” As of May 2019, he had made 1,777 eBay purchases. He swiveled his monitor toward me and scrolled through his 100 percent positive buyer feedback. He had even enlisted some eBay acquaintances in his cause. One such contact was a “magical man” in California who combed through estate sales and put aside any records he thought Levin might want. The man was possibly homeless. When I asked for his name, Levin couldn’t recall it. “I know his eBay handle,” he said. Levin receives two to three packages in the mail per day. At the time of my visit, the three desks in his office were covered with books, audio equipment, and records, but Levin explained that at the end of the school year he clears one off, so that the office staff has a place to leave his packages. Beside his desk were three twenty-five-gallon plastic file boxes. “These are my course papers and teaching files,” he said. He was having a space problem, and the papers would have to go.

He played me the voice of Bette Gaines, in New York. Bette Gaines was sending her greetings to “all you girls” back in Pasadena, California. I still don’t like the subways, although I’m not quite so scared anymore, she said. First, I’d get on the wrong subway and go the wrong direction, then I’d get on the wrong subway, go the right direction, then get on the right subway, go the wrong direction. One morning I got on the right one and I went the right direction.

It almost overwhelms you to see the people here, she said. It’s never-ending; they swarm over the streets.

Bette was candid, sincere, at times even buoyant. But beneath her carefree enthusiasm she sounded self-conscious. I made a remark about this. Bette sounded as though she were addressing two different audiences: “all you girls,” but also an unknown future listener, someone who might come across the recording long after she was gone.

Levin gazed at me with a certain remoteness. “Exactly,” he said. “Here I am.”

It seems we have given up voice mail for reasons vaguely related to efficiency. Leaving a voice mail requires self-composure and a quiet place, but text—though we may lament this aspect—is a medium for any time. You can type out a text under a conference table, at a bar, or on a run. You can read a text slyly, you can skim a text, and you can respond with an emoji as emotional shorthand. But a voice mail holds you captive for twenty, thirty, even sixty seconds. For some of us, the pace of natural human speech is just too slow.

It is a shame we have become so disenchanted with voice mail. For the better part of our history, voice was understood to be ephemeral, as impossible to bottle as moonlight or thought. A provincial encyclopedia from Qing dynasty China, for example, describes a miraculous instrument. The device, supposedly conceived by the court inventor Chiang Shun-hsin, was called the “thousand-mile speaker.” It allowed a person to talk into a cylinder, seal it shut, then send it over distance. When the recipient broke the seal, the message resounded in the air. A 1632 French manuscript describes a similar phenomenon in the South Pacific. A race of people with no art, technology, or alphabet corresponded by speaking into sponges, which were squeezed upon receipt.

Rabelais also dreamed of recording sound. In chapter LVI, book IV of Gargantua and Pantagruel, Pantagruel and his cohort arrive at the site of a battle. Scattered on the ground are prisms of ice. The battle had taken place in winter, and these prisms contain the frozen sounds of warfare. But the weather has grown warm and the racket is melting. Shouts, neighs, and the clangs of weapons release into the air:

[Pantagruel] threw on the deck before us whole handfuls of frozen words, which looked like crystalized sweets of different colors. We saw some words gules, or gay quips, some vert, some azure, some sable, and some or. When we warmed them a little between our hands, they melted like snow, and we actually heard them, though we did not understand them, for they were in a barbarous language. There was one exception, however, a fairly big one. This, when Friar John picked it up, made a noise like a chestnut that has been thrown on the embers without being pricked. It was an explosion, and made us all start with fear. “That,” said Friar John, “was a cannon shot in its day.”1

In all of these renditions, voice mail relieves us from our bodily limitations. It allows us to contract geographies, recover lost time, and influence the living from the afterlife. Edison was especially attracted to this last application. An early press release for the phonograph strikes a morbid tone: “We have already pointed out the startling possibility of the voices of the dead being reheard through this device… When it becomes possible, as it doubtless will, to magnify the sound, the voices of such singers as Parepa and Titiens will not die with them, but will remain as long as the metal in which they may be embodied will last…” In 1906, Edison’s competitor Victrola arrived on the market. Victrola’s mascot was a white terrier named Nipper who peered into a gramophone horn. The artist who designed the logo had a dog just like Nipper. He had inherited the dog from his brother, and when he played a recording of his late brother’s voice, Nipper put his face to the horn and cocked his head.

When the Voice-O-Graph debuted, in 1941, the device’s potential to bring back the dead was alive in the minds of those who used it. The Voice-O-Graph was tall and coffin-like. Out of the smoke and darkness of a game hall, its red-and-orange lettering beckoned.

STEP IN! RECORD YOUR OWN VOICE!

A smaller tagline described another feature: hear yourself as others hear you.

In the 1940s this was a real novelty. Few people had ever heard their voice played back to them from a recording. The Voice-O-Graph booth was often their first experience with a microphone. As a consequence, many recordings capture the strange and specific moment when the speaker understands that their voice can be extracted from their body and stored in an object, where it might one day outlive them. Under the pressures of a live microphone, a ticking timer, and the threat of unbearable silence, some people digressed and arrived on the subject of death.

In Berlin, two parents made a record for their sons. Should we not be around one day, this record should be a small souvenir and remind you that we always want to be around you, and only want the best for you…, says the mother. That’s our biggest wish. And our blessing should always be with you.

The recordings in Levin’s archive capture a range of human emotions. People step into the Voice-O-Graph booth to declare their love, sing “Happy Birthday,” or give an account of their day’s minutiae. Little girls sing patriotic songs. There is anxiety in front of the microphone. There is self-conscious silliness under media duress. There are quick catches of personality, truncated and oblique, each an extract from a life no longer being lived.

Levin has several goals for his voice mail collection. He is conducting his own research and has authored several papers on the materials. He is also digitizing the archive. He anticipates that the material will be of interest to all kinds of scholars: linguists, sociologists, philosophers, genealogists, historians of everyday life.

Now that he has amassed a veritable archive, a change has occurred in his acquisition process. In the beginning he was on his own, surveying the vast, uncharted territory of eBay from a swivel chair in his faculty office. But now he has a reputation. When people turn up old Voice-O-Graph records in their attics, they find Levin online and get in touch.

At the time of my visit, Levin was giddy over a recent email from Claire Lissance, of Placitas, New Mexico. The subject line read: “My father invented the Voice-O-Graph machine.” Levin had her on the phone within the hour.

Claire is a retired career counselor in her mid-sixties. She told Levin that her father had died in 1972, but that she had not gone through his belongings for some years. It was only in 1998, after the death of her mother, that she began to excavate the family apartment in earnest. While sorting through some family papers, she came across a dossier containing correspondences and schematic drawings on Mutoscope letterhead. Most of them concerned a machine called the Voice-O-Graph.

The phone call with Claire had been thrilling, but it also set Levin on edge. These were sensitive matters. He was highly interested in the materials she might have, but did not want to seem too eager, lest he scare her off. He was also concerned that her archive might find its way to someone else first. He suggested that if I were to ever cross paths with another collector of gramophonic epistles, I might take care with what I said.

About three hours south of Princeton, in Newark, Delaware, lives a patent lawyer named Bill Bollman. Neither Levin nor Bollman would refer to the other as a rival, though another word does not easily present itself. Until recently, Bollman lived in a 1940s colonial home in Bethesda, Maryland, with a finished basement that he had excavated an additional six feet to accommodate an indoor basketball court and a climbing wall. Bollman is even-keeled and low-energy, and talks deliberately, almost drowsily, which may come from a lawyerly habit of verbal precision. He has a few secondary interests. One of them is college basketball. Another is the Mold-A-Rama, a coin-operated vending machine from the 1960s that melted colored wax into collectible tchotchkes. Through the years, Bollman’s interest in the Mold-A-Rama has developed into a more general interest in coin-operated machines, which he now collects in large numbers. When he still lived in Bethesda, he kept his arcade games in a room adjoining the basketball court. He had, among other items, a 1961 Shooting Gallery, a Ms. Pac-Man, and a 1956 Vendo 81 soda vending machine, which he kept stocked with eighty-one bottles of soda.

A sizable part of the vintage coin-op machine economy is predicated on trades. Collectors like Bollman fix old machines and trade them for ones in need of repair. Some years ago, Bollman negotiated a trade with a collector in Chicago. Among the items Bollman picked out was a tall, narrow booth that had seen better days. It had been painted forest green, and at some point had been outfitted with a 1950s-era rotary telephone.

The collector in Chicago hitched a trailer to his truck and drove the booth to Maryland. When he reached Bollman’s home, the two of them wrestled the booth into the garage. They were unable to stand it upright, so they laid it on its back. It disintegrated immediately. “It was like one of those slow-cooked steaks that flake apart with your fork,” said Bollman. In his garage, Bollman care-

fully stripped the green paint. Underneath, in plump, slanting script, were the words record your own voice.

Bollman fell in love, and ever since, he has been searching the country for Voice-O-Graph machines. When he finds one, usually in some barn or garage in the middle of America, he buys it, restores it to working order, and resells it at a premium. His connections in the picking world keep him apprised of booths in the wild. Once he gets a booth back to his workshop—at the moment a thirty-by-thirty storage locker in Delaware—he starts the rehabilitation process. He has a machinist who redoes the mechanism, a sign painter who restores the lettering, and a guy who specializes in the cutterhead, the component that cuts the record. Much of his work is accomplished by trial and error. In the beginning, he had to experiment with plastics to find a compound that would work for the record blanks. The original Voice-O-Graph records were made from cardboard coated in shellac. When the cutterhead carved through the virgin shellac, it displaced a thin, spiraling curl. This curl was called the chip. But the chip and its associated crumbs were highly flammable. Bollman’s restored machines now cut records from a clear, non-flammable plastic. “All put together, it gives you that wow factor,” he said. “People make a record and it’s kind of cool.”

These days Bollman has a monopoly on the market for Voice-O-Graph booths. He is one of the few people who knows where to find them, and the only one who can get one into working order. Because few booths have survived, and because they are so difficult to transport, the collecting is slow going. Sometimes Bollman will track a single booth for years.

One booth was on his radar for nearly a decade. The booth was not particularly desirable when it first went up for auction. It had been painted over, and the mechanism was missing. Bollman didn’t bid on it. Some years later the booth traded hands again, this time to the magician David Copperfield. But Copperfield soon regretted the purchase. “He’s a big buyer, as you can imagine,” said Bollman. “He likes complete. He likes original.” So Copperfield rang up Bollman, then offered him the booth. Bollman took it, and when he stripped off the paint, he found beautiful original lettering underneath. “David was like, ‘Damn. I should have kept that one.’” Bollman’s other clients include Jack White, Quentin Tarantino, and “a fellow from Metallica.” When I asked him how many Voice-O-Graph booths were presently in existence, the lawyer responded: “The number is under twelve.”

For a period of time, Bollman also collected Voice-O-Graph records. He could get a sense of Mutoscope’s distribution based on where people said they were speaking from, and sometimes the labels clued him in to models he had not yet researched. At one point, Bollman had about eight hundred records, most of which he purchased on eBay. No one else seemed to be bidding on them, so he could get them for around five dollars each. But after some time Bollman noticed the prices going up. Someone else was placing bids. Eventually the other bidder reached out to him. The two struck up a deal: Bollman stopped collecting Voice-O-Graph records, and in exchange for a payment of an undisclosed amount, he packed up his collection and mailed it to an address in Princeton.

“It wasn’t a turf war,” said Bollman. “We were on the same turf.”

Levin and Bollman are the only two major collectors of Voice-O-Graph materials in the world, and in many ways they are each other’s opposites. Bollman is the Voice-O-Graph’s physician. He diagnoses a booth’s ailments and brings it back to life. Levin, on the other hand, is the Voice-O-Graph’s analyst, its interpreter of dreams.

Levin and Bollman have met a few times in person, and they generally keep in touch. They share their discoveries with each other, as they must, for each one’s enterprise is helped along by knowledge only the other can provide. They still occasionally outbid each other, and closely guard their sources. But they must share information, and even take pleasure in doing so. After all, who else can Levin talk to about the Voice-O-Graph machine? And who else can listen to Bollman’s barn-scouring tales and respond in kind?

Most of the recordings in Levin’s archives are mundane, but a patient listener will eventually chance upon the extraordinary. One recording begins routinely enough. A soldier speaks to his wife and children from a military base. His voice is light and cheery. Hello, Mary and Catherine and Charles. How is everybody? Yes, I’m feeling pretty good. Soon it dawns on the listener that things are not so good. Yep, chopped the darn thing off, four inches above the knee, he says. I lost my leg, but forget it. Let’s all laugh.

“Do you have any Spanish?” Levin asked me from his desk. He placed a record on his turntable. “No? Doesn’t matter. Why? If you attend to the pauses, you will understand it. Shall I play a little?”

The record was seventy-five years old. It was sent to René in Argentina in 1945.

A man’s voice filled the room. Quiero yo por siempre estar a tu lado en un sueño de amor, de este amor eterno, René. Sueña, René. Quisiera amar tus ojos. Yo estoy a tu lado con mi cariño, René.

The man’s voice was nearly a whisper. He paused between phrases, and breathed heavily into the microphone.

Quiero besarte. Te beso, René, te beso. ¿Me quieres, René? ¿Me quieres? ¿Tanto?

“I want to KISS you!” Levin shouted over the record. “Do you WANT me? Do you WANT me, René?”

¿Como tantas estrellas hay en el cielo? En la noche calma, tantas suspiras y armonías para nosotros dos.

“The STARS in the SKY! And the CALM NIGHT! It’s BEAUTIFUL, eh?”

The man sounded exhausted, desperate. At times he was barely audible. Every time he uttered “René,” his voice dropped to a lower volume. He whispered René’s name over and over as nothing more than a puff of breath, and was all but subsumed under the record’s white noise. It was the sexiest thing I had ever heard.

On a rainy morning in May 2019, Claire Lissance arrived in Princeton for a tour of Levin’s archive. Lissance and Levin spent the afternoon opening the day’s eBay shipments. They listened to some records, and Lissance shared stories about her father, the inventor of the Voice-O-Graph machine.

I spoke with Claire on the phone shortly after her visit, and she told me about her family. She grew up in Spuyten Duyvil in the West Bronx in the 1960s, and was her parents’ only child. Her father had been older than the other fathers. He was fifty when she was born, but looked young for his age, and for most of Claire’s childhood her parents kept his age a secret from her. His name was Alexander Lissiansky, but most knew him as Sacha. He rode motorcycles as a young man, collected clocks, and read physics textbooks for fun. He loved things that ticked and clicked, but as much as he loved machines he loved people. If on a weekend in 1955 you found yourself outside a street-corner garage in the Bronx, you might have glanced inside and seen an elegant older gentleman in a sport coat keeping company with the mechanics.

He was also a man who suffered. He struggled with illness throughout his life, although Claire’s mother was not always forthright about his afflictions. When Claire was in high school his health worsened, but it took another two years before her mother disclosed that he was sick with cancer. Such matters were not openly discussed in the Lissiansky household. By the time Claire was born, her father had left International Mutoscope. The company was long gone. Claire regretted that she had never asked her father about his work. He rarely said much about it, and she had been young and preoccupied with other things. He died on Claire’s last day of high school. “It was the usual thing,” she said. “It was terrible. It was at home. There was nothing spared.”

Years later, when Claire went through her father’s papers, she found correspondences between her father and a man named William Rabkin. Rabkin was the president of International Mutoscope and the mastermind behind its products. By the time Rabkin hired Sacha, in the late 1930s, he had grown the company into one of the largest manufacturers of coin-operated amusements on the East Coast. The company’s flagship offering was the eponymous Mutoscope, an enormous iron Rolodex that played silent, flickering peep shows with such racy titles as “Loose Ankles!” “Ladies’ Night in a Turkish Bath,” “Girl Climbing Apple Tree.” In later decades, the company diversified its offerings to address the full range of primal desires. International Mutoscope made machines for romance (the Love Pilot) and machines for violent urges (the Punch-A-Bag, the Drop-Kick). For those who stood anxious before the unknowable future, there was Grandmother Predictions, in which a wizened woman made of wax would dispense, after a series of mechanical lurches, a card revealing a fortune.

Rabkin was born in Babruysk, Belarus, in 1894, and emigrated to New York as a teenager. He smoked several fifty-cent cigars a day and was a thirty-second-degree Mason. He nearly bank-

rupted the company twice with his charitable giving, and rarely set foot in his own office, preferring to work from a small room off the main corridor with the door propped open so that he could intercept anyone who walked by. He left work at 7 p.m., attended an evening program of board meetings and cultural events, returned home at one in the morning, and was in bed by two. He set two alarms clocks, one at his bedside and one across the room. When the alarms went off at six, he began his day anew.

Claire’s neighborhood in the Bronx had been diverse. “When you’re in New York City, you’re never far from another country,” she said. Most of her friends and neighbors were also from immigrant families, so it did not occur to her that by the standards of most New Yorkers, her father spoke English with an accent. Like Rabkin, he was of Russian Jewish descent. He was born in 1904 in Odessa, Ukraine, but grew up in Vienna, where his parents ran a shoe factory. Sacha worked in the factory from a young age, and Claire believes this is where his interest in machinery deepened. By his twenties he was designing prototypes, and by his thirties he had moved to Paris to promote a new invention: a coin-operated recording machine that captured the human voice.

The year was 1931, and while Sacha’s career was full of promise, the political situation was inconvenient. Europe’s economies were still reeling from First World War, and Austria had been hit hard. Back home in Vienna, the Lissianskys were forced to liquidate the shoe factory. Misfortune built upon misfortune. Without the factory to keep him busy, Sacha’s father, Moses, was beset with health problems. His lingering heart condition worsened, and he had to have a leg amputated above the knee. He wrote in a letter to his son: “Generally speaking I and Mama, with her back trouble, are realizing that we are just two old, worn-out machines.”

Years passed, and the situation worsened. “The picture of Vienna is totally changed,” wrote Sacha’s mother, Gitel. “There are huge swastika banners everywhere, and a gigantic electrical swastika is blazing for the Kahlenberg and Leopoldsberg hills every night. Goering has promised that he will soon have Vienna judenfrei.”

The Lissiansky parents put in applications for American visas, but their prospects were grim. Any family applying for residency in the United States had to prove they would have income upon their arrival. The Lissianskys were retired and infirm, and like all Jewish citizens under Nazi rule, they were forbidden by law to work.

Soon after Claire’s grandparents filed their affidavit, however, someone from an American company must have spotted Sacha’s recording machine. There is little information about who this investor was, what company he was with, or under what circumstances he met Claire’s father. But suddenly, Claire’s father was on his way to New York City on official business, as an exhibitor at the 1939 World’s Fair. Shortly thereafter, her grandparents’ apartment in Vienna was vacant.

On the 1940 census, the Lissiansky household in New York City is home to seven. There are Claire’s grandparents, Moses and Gitel. There is Claire’s uncle Syoma, his wife, and their two sons, whose previous residence was Prague. And there is her father, Sacha Lissiansky, previous residence Paris, who is single and unmarried, but whose work in a field described only as “Other” brings in enough money to support them all.

By the time I spoke to Claire, I had been listening to the recordings in Levin’s archive for some time. The experience had left me a little forlorn. No single recording told a full story; each was a fragment from the very middle of a stranger’s life, a fossilized bit of time whose larger context had been lost. You would hear the edge of personality, the hint of shyness, the moment of violent longing that rose up, then diminished. None of the recordings were satisfying, nor did they provide any cohesion of meaning. At the same time, they felt thick with meaning. To listen to a few of them was often boring; to listen to the glut of them was profound. One realized that human experience transpires in language, and yet the breadth of this experience is so large that the very language that accounts for it cannot, in the end, describe it.

All archives are like this, and anyone who has spent time in a rare-books room knows the layered feelings of exhilaration, helplessness, and melancholy that come with such encounters. And yet the voices in Levin’s archive gave a startling impression of nearness that I had not encountered elsewhere. Text may conjure sound in the mind, but voice is a disturbance of the atmosphere. It occurred to me that the records were physical impressions of presence in the same category as a death mask, a footprint, or a calcified-ash body in the streets of Pompeii. All the events in a person’s life might lead him to a booth on a boardwalk. There, he might blurt out something rash or painfully self-conscious, changing the air around him, and causing a needle to vibrate around a disk. Should the disk be played back after many years, the air will change in the same way, though the person speaking may have vanished.

By 1948, International Mutoscope had two hundred employees and was grossing over two million dollars most years. Shortly thereafter, the company was bankrupt. There is little information on the final days of Mutoscope. The company has no archive, though the warehouse in Long Island City, New York, still stands.

After the mechanics at International Mutoscope assembled a new Voice-O-Graph booth, the final step was to make a test recording. These test-recorded disks were never meant to be listened to, but sometimes they were affixed to the inside of the booth to advertise the end product. In his ten years of collecting Voice-O-Graph materials, Bollman has come across a few of these.

This is a test recording, says one mechanic. This is the first record that is being cut on this machine. He speaks to someone off-mic. Thank you. You’re very kind. Very considerate today. I sure appreciate it, being that this is Saturday, the day of rest, the Sabbath. The gentlemen here are complaining about their coffee. I think you better do something about it, Willy, or else you’ll have a revolt on your hands!

There was no time for leisure for the employees of the International Mutoscope Corporation of New York. “Willy” Rabkin kept them working through the weekend. By the time Claire’s parents married, her father had stomach ulcers so severe that his diet was restricted to milk and rice. Bollman does not know why Mutoscope folded, and neither does Claire. She does know that Rabkin “either fell or jumped out a window.”

There are four functional Voice-O-Graph booths presently available to the public. All are working as a result of Bollman’s handiwork. Two belong to Jack White. One is located at Third Man Records, White’s record store in Nashville, Tennessee. The other is in the store’s second location, in Detroit. On a rainy day this past spring, I took a trip to Detroit.

When I walked through the front door of Third Man Records, the booth was right by the entrance. To the untrained eye, it might appear to be a phone booth. It is tall and narrow, with rounded corners and a warm wood finish. I bought a token at the counter. The woman at the register told me that the booth had been difficult to keep in working order. It was fragile and broke down often. Lately, it had been working OK, although every so often it cut off the first ten seconds of a recording.

I stepped inside the booth and found myself in an exceptionally narrow space. I thought about the recordings I had heard in which several people could be heard at once—they must have been standing on top of one another.

There was a caged microphone, a sign with instructions, and little window that showed the turntable and mechanism. I dropped my token into the slot. The booth made a loud grinding noise and began to rattle. Vibrations came up through my feet. I would not have been surprised if the walls had fallen down around me, or if the whole thing had lifted off into space. I watched through the window as a mechanical arm picked up a plastic disk from a stack and moved it over to the turntable. The record dropped and the stylus made contact. Then the booth stopped shaking. The grinding ceased. A light went on. A counter, set to 150 seconds, began to tick down.

Suddenly, I found myself announcing my name, location, and the date. The gesture was rote, and had existential valence. I rambled off some message. When the time was up, the machine played my message back. Just as the woman at the counter had warned, the part where I announced my name, location, and the date had been wiped. All that remained was my message, which had been rendered anonymous.

I got a stamp at the counter, mailed the record to a friend, and went to catch the bus.

Before Bollman handed over his Voice-O-Graph records to Levin, he liked to listen to them en masse, in rough chronological order. He said that if you listened carefully enough, you could hear the subtle transformations of a collective feeling. In the early years of the Voice-O-Graph, the records were light and lively. Nearly everyone commented on the technology itself. It was a brand-new trick, exciting and strange.

So we’re walking down the avenue, and all of a sudden Sal decides we have my voice recorded. And I didn’t believe it at first, but here we are! I don’t know what’s happening, but it is!… Gee!… How do I sound, Mother? Do I sound all right?

Starting around 1941, a certain desperation emerges in the recordings. Upon American involvement in World War II, Mutoscope turned over its equipment to the war effort. The United Service Organizations began touring military bases with Voice-O-Graph machines. Soldiers recorded messages for their wives, and their wives sent replies.

I only got about thirty more seconds… I miss you very much, honey. And I wish I could be home. But it don’t look like for another six or seven more weeks before I get that furlough and then off I go. Where, we don’t know, but we’re pretty sure it’s Japan.

After the war, lightness returns. The recordings become silly, mischievous, and jubilant. One captures a young man on Christmas Eve, slurring rather emphatically.

Hello there, Bill. How ya doing? A light just went on—ha! Oh boy, I’m feelin’ fun, Bill… We’ll get drunk when we come stay, then we’ll have a good hallelujah… Hallelujah and a Merry Christmas. I wonder if my time’s up. I hope not… I wish you a very, very happy New Year. And don’t forget to get drunk. Goodbye and farewell. Time isn’t up so I’ll keep on talking till they stop. Hallelujah, Bill.

One general sentiment unites the recordings over the decades, and this is a mundane yet persistent sort of longing. Many who entered the Voice-O-Graph booth were away from home, and in their recordings they express a desire to be reunited with the ones they love.

Hello, darling, says a man. How’s that darling wife of mine today? Still love me? Oh, what’s the matter?… Well, darling, here I am, way out here in New York. God, how I do travel. Someday, yeah, soon, I hope, we’ll both be back, back together again, then, when we can pick up the life just where we left off…

Buildings and monuments may be the landmarks of long time, but short time is measured in household objects. As dishes change places on the breakfast table, the table becomes the chronometer of Sunday morning. One could even argue that the texture of reality is no more than our accrued encounters with everyday artifacts. We can number our days in credit card swipes, thumb taps on a touchscreen, and ear buds in the ear. These gestures have a way of gathering in our haptic memories until they become so woven into the grain of living that they become time itself. But common things are unstable, inclined to change over the decades. Years ago, many a sleeping typist heard the ding and thump of the carriage return in the office space of her dreams.

If we can infer past mentalities from the clutter of yesterday, then the Voice-O-Graph might tell us something about a prior emotional reality. Before the arrival of the telephone, the world was a much bigger place, and its corners were obscure. Word traveled at the speed of the mail carrier, and falling out of touch was easy; it was the regular order of the universe. The distances, too, felt especially vast. Many of the young, rambunctious men who pulled their girlfriends into recording booths would in a few years disappear overseas. Meanwhile, in Europe, millions of families fled their home countries. Levin’s archive is filled with the recordings of immigrants. They are in German, French, Italian, and Dutch, and were mailed from the United States to family elsewhere. It is unsurprising that this technology would catch on among the displaced and the dispossessed. Sacha Lissiansky was himself a refugee and understood the emotional consequences of migration. When there is a chance you may never see your family again, you need more than a letter. You need a way to freeze the present, to contract space, to conjure a person in the air. The Voice-O-Graph offered a solution, but its limitations are evident in every recording. A spoken letter is not the same as an embrace. A recording may allow the absent to speak, but their words are finite. Only a living person can surprise you.

These days, our efforts to keep in touch do not strike so desperate a tone. Easy access to cell phones and email reassures us that we won’t fall out of contact, so we refrain from expressing our wildest yearnings and trust that there will always be another chance. We end up neglecting to acknowledge that one day the people we love will be truly unreachable. Every timer eventually runs down. Whether we like it or not, the recording will be cut off. What, then, will remain of us? Text messages are an intangible residue, but the Voice-O-Graph offered physical evidence. The machine granted those who dropped a coin into its slot the chance for an earthly afterlife. Legs are lost, and countries, too, but a drunk man on Christmas Eve can be drunk forever, and a man in Argentina in 1945 will always dream of René. Levin’s collection is an archive of ghosts.

The Voice-O-Graph gave the Lissiansky family an afterlife too. The income from the machine allowed them to carry on until their lives’ natural ends. Once settled in New York, Sacha’s father, Moses, enjoyed walks along the Hudson and reading the Russian-language newspaper in Fort Tryon Park. One afternoon, while reading the paper, he came across an advertisement for a new Jewish cemetery in Passaic County, New Jersey. He paid a visit and took a tour. A large plot beneath a maple tree caught his eye. But the plot was too expensive, so he purchased a smaller one, farther from the tree. He died a year later, in 1943, and was buried in Passaic with his artificial leg.

When Claire was a child, her family was not particularly wealthy, but her mother insisted this hadn’t always been the case. “When I married your father, he was a well-to-do man,” she used to say. Once upon a time, her father had had enough money for a Buick convertible. He had dressed himself in fine suits. And in his seven years at Mutoscope, he had made enough money to buy the cemetery plot on which his father had set his heart. He arranged for his father’s body to be exhumed, and reinterred him beneath the maple tree. Sacha’s mother lived until 1956, and when she died she was buried in the same grave, next to her husband of forty-one years.