On the night of February 25, 2010, a mob of hip-hop fans huddled in Toronto’s Kool Haus, shouting, “It’s not him” and “Get the fuck off the fucking stage.” The subject of their ire was the mercurial Daniel Dumile, better known as MF Doom, the spastic, inventive rapper who has, since 1999, concealed his face behind a metallic gladiator mask. (Dumile has also created additional rap characters, including Zev Love X, Viktor Vaughn, and King Geedorah.) Onstage, a man of approximately equal size to Dumile made vague rap gestures—gesticulating hands; nodding head; slow, rhythmic stroll—but rarely let the mic leave his mouth, even for ad libs. For a rapper who’s supposed to be garrulous and crude, the tight-lipped dude hardly seemed to be keeping it real.

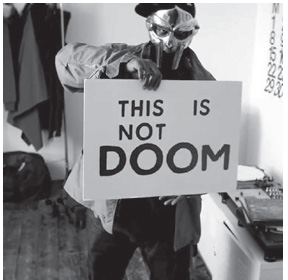

There had already been a spate of incidents like this one. Dumile’s reliability, which has been called into question regularly, was disputed most aggressively between 2007 and 2012, owing to his use of performing standins, known variously as “Doomposters” or “MF Dupes.” In a 2009 interview with Ta-Nehisi Coates in the New Yorker, Dumile, who has alternately denied and affirmed the yarns spun by conspiracy theorists, ascribed a theatricality to the stunts: “I’m the writer, I’m the director. If I was to go out there without the mask on, they’d be like, ‘Who the fuck is this?’”

The story of Black Bastards, the sophomore effort from KMD, Dumile’s pre–MF Doom rap group, might shed some light on that question. Planned for release in 1994, the album was allegedly shelved by Elektra Records for its seditious cover illustration: a Sambo figure hanging from a gallows, the album’s title spelled out as a game of hangman: BL_CK B_ST_- RDS. Scoffing at the label’s reluctance to release the album, rock critic Robert Christgau urged readers to “make a face at Elektra.”

In tandem with Dumile’s own ecstatic imagination, the music industry’s early ambivalence toward Black Bastards may be why he makes all of his faces: to reclaim ownership of his career, his narrative. “…if there’s going to be a first impression I might as well use it to control the story,” he told Coates. “So why not do something like throw a mask on?”

Indeed, why not? This is the same man who says, as his alter-ego Viktor Vaughn, “Dub it off your man, don’t spend that ten bucks. / I did it for the advance, the back end sucks.” When Dumile jokes in the New Yorker interview about sending “a white dude” and “Chinese niggers” to perform as MF Doom, it’s hard not to read in his antics a rebuke against both the trappings of the music industry and the strict, if understandable, expectations of fans who think they have him figured out. Dumile embraces not only his provocateur status but also the racial coding behind it; on the Vaughn album Vaudeville Villain, he calls himself a “shuck-n-jiver.”

According to Valerie Cassel Oliver, editor of Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art, black performance art is “rooted in spectacle and… occupies the liminal space between black eccentricity and bodacious behavior, between political protest and social criticism.” To wit, Adrian Piper’s 1973 piece The Mythic Being navigates physicality and disintegration by creating, in the words of Naomi Beckwith, “a live character in the public realm and… a visual representation in drawings and advertisements.” David Hammons’s 1983 Bliz-aard Ball Sale, for which the artist vended snowballs on a street corner, critiques the art world’s high capitalism. William Pope. L’s The Great White Way, begun in 2001, was an intermittent nine-year, twenty-two-mile crawl up Manhattan’s Broadway in a Superman costume. The late interdisciplinary artist Rammellzee often materialized in public masked as one of twenty-two characters he’d created. In the context of this lineage, Dumile’s antics lay bare his desire to commodify his own artistry by simultaneously selling spectacle and appearing nowhere.

The reissue of Black Bastards, released for Record Store Day in 2015 on Dumile’s own label, Metal Face Records, is housed in a pop-up board book, recalling not the iconic Little Golden Books series so much as The Story of Little Black Sambo, Helen Bannerman’s controversial 1899 book whose titular character has become a murky relic of the Jim Crow era’s “darky iconography.” The Sambo figure’s face recurs throughout the book with an anti-sign superimposed on it. (The cover’s “hangman” pun is typical Dumile, as it should be—its illustrator is The Emef, yet another of his personas.)

The book also includes a picture of Dumile as Zev Love X, one of his only self-released unconcealed photos in recent memory. It’s fitting, in a sense, that his reinvention of Black Bastards as memoir comes as he continues to distance himself from the conventions of performing (at a recent festival, he literally phoned in a pre-recorded routine). It helps us appreciate his two-step between seriously evoking racialized characterizations of performing black people and flippantly alluding to his PR stunts; between the authenticity expected of a singular author and the honesty afforded by multiplicity; and between real-life eccentric and mythic being.

On “Biochemical Equation,” a 2005 track with RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan, MF Doom wonders:

He wear his beard like a frizzyhaired grizzly

And kept his appearances exquisitely rare—where is he?

Is he in your backyard or on your front porch,

Or standing in the corner of the club with the blunt torched?

Kool Haus patrons probably had similar questions that confusing February night. MF Doom eventually turned up at the club, emerging to perform “Accordion,” a popular cut by Madvillain, his collaboration with the producer Madlib. The audience put on their happy faces.