This other Eden, demi-paradise, this precious stone set in the silver sea, this earth, this realm, this Los Angeles.

—Steve Martin (and Shakespeare), L.A. Story

The entire world seems to be rooting for Los Angeles to slide into the Pacific or be swallowed by the San Andreas Fault.

—Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear

Experience the beauty… of another culture while learning more about wastewater treatment and reuse.

—Brochure for the combination water reclamation plant and Japanese garden in the San Fernando Valley

PROLOGUE: FROM WALDEN TO L.A.

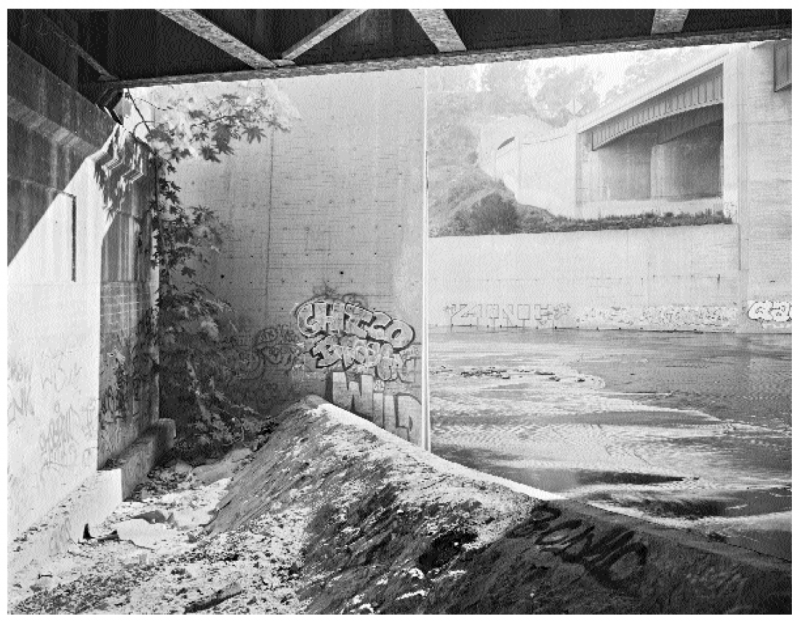

There are many places in L.A. you can go to think about the city, and my own favorite has become the Los Angeles River, which looks like an outsize concrete sewer and is most famous for being forgotten. The L.A. River flows fifty-one miles through the heart of L.A. County. It is enjoying herculean efforts to revitalize it, and yet commuters who have driven over it five days a week for ten years cannot tell you where it is. Along the river, the midpoint lies roughly at the confluence with the Arroyo Seco, near Dodger Stadium downtown. L.A. was founded near here in 1781: this area offers the most reliable aboveground supply of freshwater in the L.A. basin. It’s a miserable spot now, a trash-strewn wasteland of empty lots, steel fences, and railroad tracks beneath a tangle of freeway overpasses: it looks like a Blade Runner set that a crew disassembled and then put back together wrong. It’s not the most scenic spot to visit the river but may be the finest place on the river to think about L.A.

Like so many writers who come to Los Angeles—and I moved here seven years ago—I have succumbed inevitably to the siren call to write about the city. The long-established procedure has been to explore why one loves it or hates it, or both, and to proclaim loudly in the process that L.A. is the American dream or the American nightmare. The tradition tempts writers with a combination of navel-gazing and arm-waving that proves impossible to resist for too long.

More urgently, L.A. is the ideal place to tackle the problem of how to write about nature. In the past twenty-five years, the venerable American literature of nature writing has become distressingly marginal. Even my nature-loving and environmentalist friends tell me they never read it. Earnest, pious, and quite allergic to irony: none of these trademark qualities plays well in 2006. But to me, the core trouble is that nature writers have given us endless paeans to the wonders of wildness since Thoreau fled to Walden Pond, but need to tell us far more about our everyday lives in the places we actually live. Perhaps you’re not worrying about the failures of this literary genre as a serious problem. But in my own arm-waving manifesto about L.A. and America, I will proclaim that the crisis in nature writing is one of our most pressing national cultural catastrophes.

I love L.A. more than I hate it. I wasn’t supposed to. A nature lover from suburban St. Louis, I have enjoyed a fierce and enduring attachment to the wilds of the Southern Rockies. I was supposed to love Boulder, Colorado, where I settled after graduate school in the hope that it might be the perfect place—and it’s a town that every day adores itself in the mirror and confirms its perfection. But by pondering all the ways of seeing nature in L.A., I can explain why I have decided that I love L.A. instead—and why the L.A. River (site of the famous chase scenes in Grease and Terminator 2) has become my favorite place in L.A., and “Enjoy the beauty of another culture while learning more about wastewater treatment and reuse” my working motto as a nature writer. Also why so many of the best-known interpreters of L.A. as the American dream and nightmare, from Nathanael West to Raymond Chandler to Joan Didion to Mike Davis, have written obsessively about nature. Why perhaps the most quoted lines in all the fabled L.A. literature are Chandler’s passage on the gale-force autumn winds:

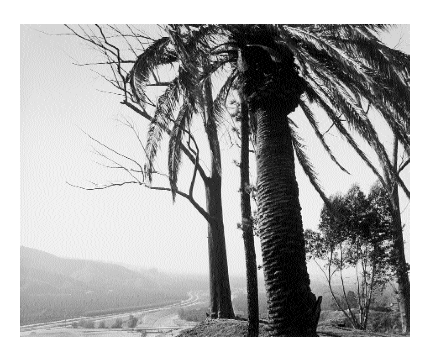

It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas…. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen.

And why we need to rewrite entirely the stories we tell about nature, and why L.A. is the best place to do it.

ONE WAY OF SEEING NATURE IN L.A.: AS NONEXISTENT

“Is there nature in L.A.?” The question sometimes betrays sarcasm, but sometimes not. L.A., after all, has long been decried as the Anti-Nature: it’s the American megalopolis with brown air, fouled beaches, pavement to the horizon, and a concrete river. It’s sort of the Death Star to American nature lovers—the place from where the destruction of nature emanates—which is why woodsy towns like Missoula and Boulder hail themselves as the anti-L.A.

And this is the reigning nature story we tell about L.A.: There is no nature here.

A SECOND WAY: AS THE WILD THINGS

But this story hews to a historically powerful definition of nature as only the wild things, which we destroy and banish when we build cities. This way to define nature—the great American nature story, and the heart and soul of nature writing—has become so firmly entrenched that seeing nature in other ways has been next to impossible.

Still, even by this inadequate definition, L.A. sports a great deal of nature: the extensive beaches, mountains, and canyons that have always brought people here. A few nature-writing anthologies include a single rogue piece about finding wildness inside a city. If L.A. symbolizes “the end of nature” (to use Bill McKibben’s dangerously catchy phrase), it actually has more than enough real fodder for such tales, if you want to write about the sunset on Broad Beach in Malibu or the hawks soaring in Temescal Canyon or the dolphins leaping just offshore or how your heart soars like a hawk or leaps like a dolphin as you watch the sun set offshore from atop the trail in Temescal Canyon.

But there are so many more kinds of nature stories to tell here. I head for L.A.’s wild spots when I can, and delight in hawks, dolphins, and sunsets as much as the next nature lover. I have a special soft spot for ducks. But the anthologies ignore about 90 percent of the nature in L.A. and all the other places we live, as well as most of people’s encounters with nature on Earth. What the crisis of nature writing amounts to, in a few words, is that Thoreau really, really needs to Get on the Bus.

And my own list of favorite representative topics for a more comprehensive, on the bus nature writing in Los Angeles would have to include mango body whips, the social geography of air, Zu-Zu the murdered Chihuahua, and Mapleton Drive near Bel Air. And, of course, the L.A. River, where all the possible kinds of nature stories in L.A. converge.

A THIRD WAY: AS THE RESOURCES WE USE

The mango body whip story begins like this: soon after I moved to L.A., a woman who ran into my car while it was parked on the USC campus left a note on the back of a receipt for a mango body whip, which she’d purchased at SkinMarket at the Beverly Center mall. What’s a mango body whip? I didn’t know. Skin product? More perverse? I made a trip to the Center, and found out that it’s a mango-infused thick and buttery skin cream.

Nature stories abound in such an encounter. Begin with the mangoes. Follow them, and you can tell an intricate set of stories as farm workers harvest mangoes in rural Mexico, and drivers truck them into the L.A. area and into the SkinMarket factory in Simi Valley—just over the L.A. County line—where workers use industrial technologies to turn them into skin butter, and distributors transport them to upscale malls like the Beverly Center, and shoppers cart them away to bathrooms in adjacent Beverly Hills and West Hollywood and to other places throughout the country.

Mango body whip stories, in other words, look for and follow the nature we use, and watch it move in and out of the city, to track specifically how we transform natural resources into the mountains of stuff with which we literally build cities and sustain our urban lives. These tales might track nature through cars. They could be about soap or magazines. They can look for the nature in refrigerators, sushi, dog food, TVs, linguine, baseball caps, closet organizers, digital cameras, bracelets, concert halls, laptop computers, bicycles. If you tell stories that follow nature through our material lives, you will see a lot of L.A.—the city’s warehouses, factories, commercial strips, and cultural centers, and its residential neighborhoods, some of which have a great deal more stuff than others.

A FOURTH WAY: AS DIFFERENT TO DIFFERENT PEOPLE

Which brings me to the social geography of air. The air in L.A., if polluted, is not equally polluted everywhere. The coastal and mountain areas, which tend to be the wealthiest, enjoy the cleanest air on average. On the inland flats, the poorest, least white, and most industrial neighborhoods in L.A. suffer the worst air, along with alarming asthma rates. Another way to put it is that the Angelenos who work in and live near the factories that manufacture mango body whips breathe far more polluted air than the residents who are most likely to be the body whip devotees. I live on Venice Beach, near Ozone Avenue—named without irony in the clean-air early 1900s, but still one of the safest places to breathe in L.A. County. Twenty miles inland, the Southeast L.A. area—the most industrialized urban area in the U.S., with many of L.A.’s lowest-income and most heavily Latino neighborhoods—occupies 1 percent of the county by acreage but generates 18 percent of the toxic air emissions.

While mango body whip stories follow nature as resources through L.A., geography of air tales narrate who encounters what nature where. These tales begin with “who.” They ask, importantly, who benefits most and who suffers the worst consequences as who uses and transforms nature. But they also ask who eats what foods and who doesn’t, and who plants what in their gardens, and who lives nearest and farthest away from a city’s parks, and who hunts and fishes or watches birds, and who chooses parrots or pit bulls or rabbits or goldfish as pets. This brand of tale asks how different people encounter nature differently.

Nature writing has ignored these third and fourth ways of seeing. It has been a literary universe in which we visit and contemplate wild nature, but seldom use and transform nature: when the mango becomes a mango body whip, it ceases to be nature, as does the oil in a laptop computer or a maple tree that becomes a table. And the genre describes nature as a unitary force or kind of place that Man encounters, and where we’ll find universal meanings—but seldom something you encounter from a specific social position and point of view.

But such a way of seeing can fully explain exactly no encounter with nature in 2006, whether in a wilderness area, on a farm, or at the Beverly Center mall. I love to go hiking on the vast trail network here in the Santa Monica Mountains. Sure, that’s a typical nature story in which I seek refuge and simplicity and quiet in L.A.’s wilds as antidote to the stress and noise of my daily life. But to narrate all the encounters with nature that define my hike,

I also have to ask where the natural resources in my Gore-tex shell and hiking boots come from—the oil, stone, metals, and animal skins in my twenty-first-century hiker gear, which keeps me warm and dry and makes my closet look like an REI outlet. How do they connect me to the global transformation of nature? And how do they shape my experience of hiking? The Simple Life out in nature is complex as hell. I’d also have to narrate how wealthier Angelenos are more likely to live near L.A.’s mountain parks—and to own cars to get to them. And how does the particular work I do at a desk all week make a strenuous weekend hike sound like a good idea in the first place? The hike has to be a story about how our connections to one another define our encounters with nature. And it’s about how the National Park Service in the Santa Monica Mountains has chosen my favorite trail routes, and how they manage fire suppression, and how they draw up hundreds of rules and policies to keep both the visitors and the parklands happy.

A FIFTH WAY: AS LANDSCAPE AND ECOLOGY WE BUILD IN AND MANAGE

Which brings me to Zu-Zu the murdered Chihuahua. As the Los Angeles Times reported, Zu-Zu’s story begins, or ends, like this: In summer 2002, a coyote entered the yard of a casting director in the Silver Lake area west of Downtown and ate her Chihuahua, Zu-Zu. Coyotes, her husband warned bitterly, are “urban terrorists”: the bereft owner said, “I have no liberty in my front yard.” A letter to the Times, though, lionized the coyote as the real victim, an indigenous animal encroached on by evil yippy Chihuahuas (if, like me, you tend to agree, then try substituting a Labrador retriever puppy for Zu-Zu).

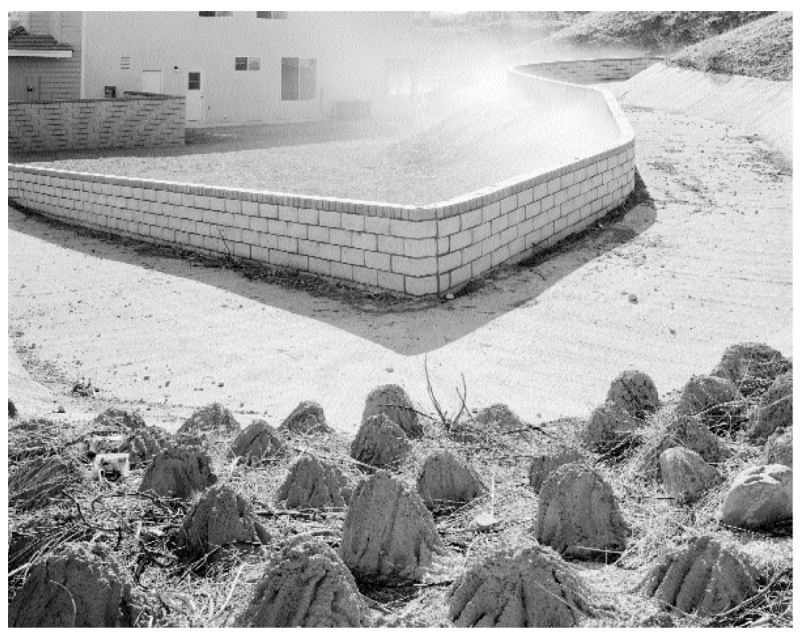

When you bring domestic dogs into a landscape of native animals, then the resident carnivores are likely to see the pets as prey. When you use and change a landscape, then the place will respond. Nature is never passive. Every place has an active, very particular ecology, climate, topography, geology, flora, fauna. Zu-Zu stories narrate how we change places and how they respond and how we respond back and so on and so on. They’re about paving, building, planting, bulldozing, fires and fire suppression, polluting and cleaning up, pet keeping and coyote predations, earthquakes and seismic retrofitting, water supply and flood management, and sewers and gas lines and lawns and gardens and roads and trails and parks.

Nature writers have in fact told this kind of story—usually, however, with an evil Chihuahua moral, in which Man stomps into nature primeval and ravages and desacralizes it. But as guidance for how we can inhabit places, seeing people inevitably as invaders in these stories works about as well as branding coyotes as terrorists. An “evil Chihuahua” moral demands that we leave the nature we live in as it is (in which case we’ll die), but a “terrorist coyote” moral urges us to eradicate nature (in which case we’ll die). Neither approach helps us navigate how to keep pet animals in a landscape with native predators—or how to make a road or build a house or ensure a water supply or figure out how to keep the air and water clean. Ideally, Zu-Zu stories should help us ask how we can create livable and sustainable cities. They should be deeply informed by knowledge of the ecology, geology, and natural history of the place. They should help us walk the essential line between doing nothing in nature and doing whatever we want. Like mango body whip tales, they should seek to understand what our connections to nature actually are so that we can think about what our connections should look like.

These are a few topics the Los Angeles Times has reported on in recent months: water deals in the West, discarded American computers shipped to China, dog parks, an L.A. landfill in the Mojave desert, the hybrid Toyota Priuses, diesel pollution in industrial south L.A., battles against new developments in the outer suburbs, new parks on the L.A. River, high silicosis rates among Chinese trinket-factory workers, oil refineries in Venezuela, farmer’s markets, the best restaurants for peach dishes, sustainable water-use practices in Santa Monica, toxic plastics residues in polar bears in the Arctic, neighborhood lawn regulations, the fight over removing the feral peacocks who scream every morning in the Palos Verdes neighborhoods, pesticides buildup in frog populations, battles for public beach access in Malibu.

These are nature topics all, about how we live in and fight about nature, and about how we use it more and less fairly and sustainably, and about the enormous consequences for our lives in L.A., as well as for places and people and wildlife everywhere. And such topics beg for a literature—for a poetry, for an aesthetics—because to clearly ponder our lives in and out of cities, we have to be able to imagine and reimagine these connections to nature.

A SIXTH WAY: AS A PREMIER SOURCE OF HUMAN MEANING

Imagine the site of Los Angeles County four thousand years ago. The people who lived here—the ancestors of the Tongva, the Chumash, the Tataviam—used birds and deer to make food and clothes, and turned trees into shelter, and turned water, rocks, and dirt into energy, tools, boats, medicine, religious objects, art. (And in 2006 B.C.E., connections to nature were not all that simple either.) The people used and changed nature in order to live. They told stories about nature to explain the world and to guide their actions within it.

What do we do in Los Angeles now? Essentially the same thing. We use nature and tell stories about it to live and explain our lives. To use nature is to be human: that’s a pretty fair working definition. To tell stories is to be a human explaining how things work. The stories that any people tell about nature are some of the most basic stories they tell. Is there nature in L.A.? The fact that the major nature story we tell in L.A., as in all cities, is that there is no nature here does not make this tale any less basic, powerful, or telling.

How do we make nature meaningful? “What nature means” tales are one last category of story I’ll suggest, and nature writing has shown great interest in this kind of story—in fact the quest for meaning has defined the genre’s very soul. Of course, nature writers have attached various meanings to a great range of places, animals, and plants. Yosemite? Majesty. A sacred place. The desert? Peace. Harshness. Clarity. Songbirds? Beauty. Delicacy. Earthquakes? Fury and vengeance. Water? A metaphor for life. But nature? The ur-meaning that frames all others? Wildness. Not-us-ness. The anti-modern. A place apart. Salvation. Refuge. And this ur-meaning historically has reigned as an exceptionally powerful American cultural assumption. Nature writing has preached it tenaciously, but hardly invented this way of seeing and of refusing to see. The vision of wild nature as counterpoint to a corrupted modern civilization has always played a central role in American national myths and identity. (Think City on a Hill, the mythic frontier, a hundred years of Westerns, and landscape photography.) To define nature as the wild things apart from cities is one of the great fantastic American stories.

And it’s one of the great fantastic American denials. On Mapleton Drive in Holmby Hills in the Bel Air area, in the Santa Monica Mountain foothills, the TV producer Aaron Spelling has built what’s widely publicized as the starship of Hollywood homes—a 56,550-square-foot French limestone mansion with 123 rooms, with two rooms for wrapping gifts and a rose garden on top of one of four garages. Here are two generally ignored facts about Spelling’s famous homestead. First, it is a house of nature: Spelling built it, has maintained it, and stocks it with fantastic quantities of oil, stone, metals, dirt, water, and wood (a likely forest’s worth of wrapping paper, to begin with). And second, there are very few maples on Mapleton Drive. Maybe maples grew here in abundance once, and maybe not. Either way, the street enjoys the idea of maple trees, which conjures a bucolic refuge above the smog, noise, and torrential activity of the megalopolis below. Call it maple mojo. Smaller manses of nature line the rest of Mapleton Drive as well as the neighboring streets Parkwood, Greendale, Brooklawn, Beverly Glen. No parks, no woods, no dales, no brooks, no glens. Just the mojo of wild nature.

Mapleton Drive showcases the denial intrinsic to the great American nature story. To say there’s no nature in cities is a convenient way of seeing if I like being a nature lover and environmentalist but don’t want to give up any of my stuff. We cherish nature as an idea of wildness while losing track of the real nature in our very houses. We flee to wild nature as a haven from high-tech industrial urban life, but refuse to see that we madly use and transform wild nature to sustain the exact life from which we seek retreat. We make sacred our encounters with wild nature but thereby desacralize all other encounters. Or in other words, if we cannot clearly understand cities and our lives within them unless we keep track of our connections to nature, still there may be some basic things we prefer not to see and understand.

Ideally, if there’s any one argument I could persuade you of, it’s that our foundational nature stories should see and cherish our mundane, economic, utilitarian, daily encounters with nature—so that what car you drive and how you get your water and how you build a house should be transparent acts that are as sacred as hiking to the top of Point Mugu in the northern Santa Monica Mountains and gazing out over the Pacific Ocean to watch the dolphins leap, the ducks float, and the sun set. True, there’s a lovely yearning in the American vision of nature as a wild place apart—for simplicity, for a slower life. There’s great wonder about the natural world, and terrific love for wild places and things. There’s legitimate bewilderment, in response to the mind-boggling complexity of modern connectedness (how could I possibly keep track of where the nature in my Toyota wagon comes from?). There’s a large dose of real regret, for the wanton destructiveness of toxic industrialism and excessive consumerism. And there’s powerful, overriding denial, in the service of powerful self-indulgence and material desire, that pushes us to imagine nature out of rather than into our lives.

RIVER TRIP #1

Just how powerful? Well, in L.A., enough to let us lose track of an entire river—not just the nature in the stuff in our houses. We can’t find L.A.’s major waterway, which sustained L.A. for 150 years and now runs under ten gridlocked freeways through the heart of L.A. County. A fifty-one-mile river in plain sight: lost.

The L.A. River is one of the city’s central natural facts. L.A. inhabits a river basin, and the major river drains large portions of three mountain ranges out to the Pacific. The L.A. Basin, while large enough for a megalopolis, is small for that much drainage, and the L.A. River consequently poses a greater flood danger than most urban U.S. rivers. (Mark Twain wrote that he’d fallen into a Southern California river and “come out all dusty”—but apparently hadn’t seen one of the raging flash floods.) In the 1930s, when a last-straw series of floods made half of L.A. canoeable, the city signed up the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who heroically proceeded to dig a concrete straitjacket for the river and all its tributaries—a twenty-five-year project that required 3.5 million barrels of concrete and remains the Corps’ largest public works project west of the Mississippi. The Corps and County Public Works rechristened the river the “flood control channel.” They recategorized it as infrastructure, with the freeways and electrical grid. To the public, in any case, the channel no longer looked wild enough to be a river or to count as nature at all. And this is how L.A. lost its river—not lost as in no longer had one, since L.A. actually still had it, but lost as in could no longer see or find it.

If a city is built and sustained through using, managing, and imagining nature, then however you see and manage your central natural facts should have massive citywide consequences. What happens when you deny that your river is a river?

The saga of the concrete L.A. River plays out as every brand of nature story. First, a “what nature means” tale: Angelenos reimagined the river as nonexistent, and banished it from their collective imagination of history and place. Also, a tale of wild things. Many birds and frogs continued to use the river (they apparently hadn’t received the memo that it was no longer a river), but other birds and most fish species did disappear, along with extensive wetlands and riparian habitat.

Also, a Zu-Zu story. As Los Angeles altered the Southern California landscape to control the river’s floods, we largely ignored the basic hydrological processes. The jacketed river could no longer flow out into its basin, and therefore no longer replenished the aquifer with water, the soils with nutrients, and the beaches with sand. The county designed the storm sewers, however, to empty into the channel, which promptly turned the river into L.A.’s Grand Sewer, which gathers pesticides, motor oil, trash, dog feces, and many hundreds more pollutants from driveways, lawns, roads, and parking lots across the 834-square-mile watershed and rushes the toxins downstream into the Pacific Ocean. And yes, floodwaters have stayed safely within the concrete walls, but the extra water from the storm sewers has actually dramatically increased the volume of the river’s floods.

The cement channel also constitutes L.A.’s strategy to move stormwater, that life-giving natural resource, through the city. Here is the river’s mango body whip story: a city that inhabits a place on Earth with a semi-arid Mediterranean climate pours as much of the rainwater as possible, which we get from the sky for free, into the storm sewers, through the river, and into the Pacific—and then pays dearly to import water by aqueduct from up to four hundred miles away. Call it watering the ocean, by draining watersheds across the West. And finally, a social geography of air story. L.A. may have wild places, but as the American city that has so consistently privileged private property over public spaces, it also historically has set aside remarkably little public park space per capita—and L.A.’s poorest areas suffer the worst shortages of neighborhood park space, enjoy the least private green space, and lie farthest from the mountain parks. In this infamously fragmented city, the poorest neighborhoods also invariably have been the most cut up by freeways and industry. The concrete channel turned the basin’s most logical site for green space, and the city’s major natural connector, into an outsize open sewer that carved a no-man’s-land through many of the city’s most fragmented and park-starved areas.

In sum, L.A.’s errant treatment of a major natural feature has profoundly exacerbated nearly all of L.A.’s notorious troubles—environmental chaos, social inequities, community fragmentation, water shortages, water imperialism, and erasure of civic memory. The good news, on the other hand—and I’ll get to the restoration efforts on the river presently—is that if you use and manage this nature more sustainably and fairly, you can make the city a healthier, more equitable, and all-around lovelier place to live in. First, though, you have to see the nature in the place. You have to find it.

*

Is there nature in L.A.? Far more than our philosophies dream of, and much more than in Portland or Boulder—more, possibly, on Mapleton Drive alone than in some small towns in Iowa. One may as well ask if there is water in the ocean. To get on the bus—to imagine a more vital and comprehensive nature writing—is to deem the question plain dumb silly, along with “Where is nature?” and maybe even “What is nature?” and especially that nonsense about the end of nature, which makes only as much sense as declaring an end to rocks or air or water and bespeaks exactly the way of thinking by which L.A. lost its river. The powering question of this literature should become, rather, What nature is it?—and then, How do we use nature? How do we change nature? How does nature react? How do we react back? How do we imagine nature? Who uses and changes and imagines nature? And often the most vital questions of all: How sustainably? How fairly? How well?

Continue with Part II

This essay appeared in an earlier form in Land of Sunshine: An Environmental History of Metropolitan Los Angeles (William Deverell and Greg Hise, eds. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005), used by permission of the publisher.