While the world is full of doors and hallways, they exist in a world of logical expectation: this is where I’ll go, this is whom I’ll see there, this is what they’ll say. However, a dream is, in a sense, an escape from predicting. Remainders of waking memory spread into farther doors and farther hallways, mazes we might never see beyond our sleep—unless, somehow, they can be rendered in waking methods, such as images or text.

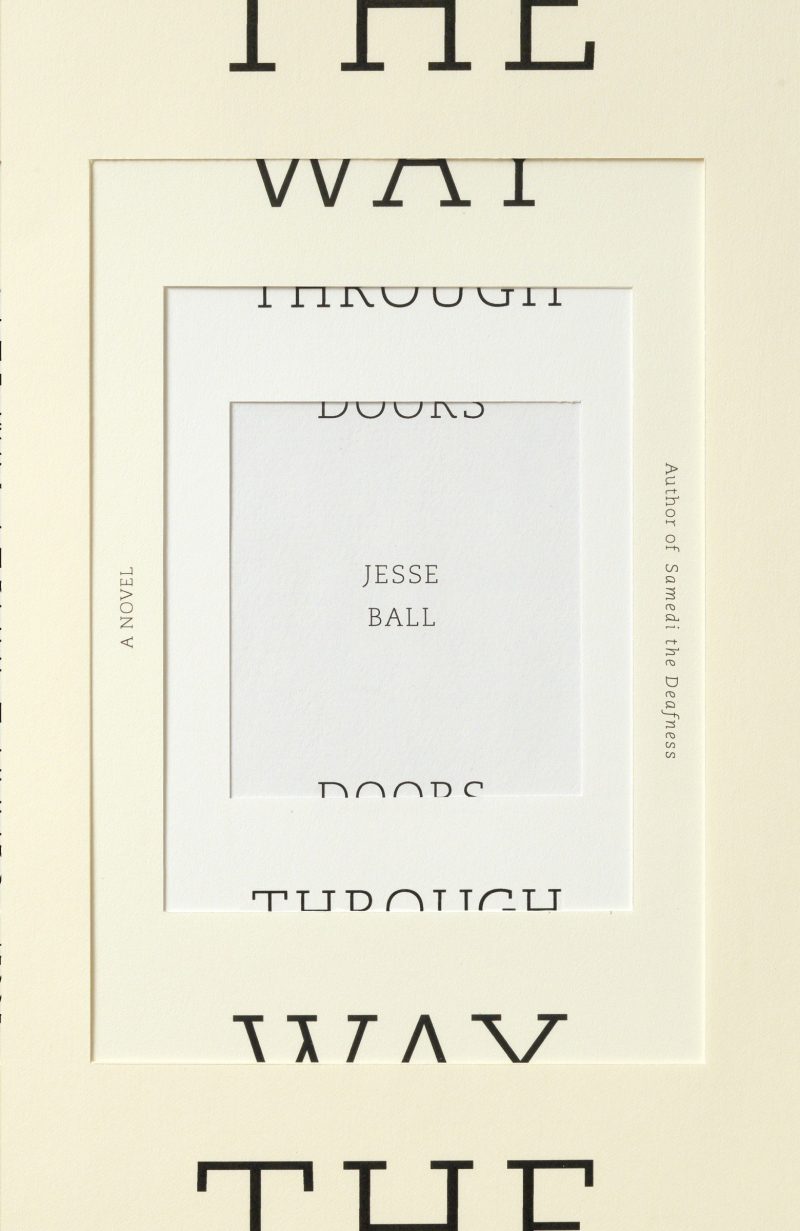

It is not by chance association that author Jesse Ball is well versed in the practice of lucid dreaming. His gift of consciously manipulating the unconscious is a talent quite clearly carried over into his new second novel, The Way Through Doors—a stunning sleep-logic lockbox so incantatory in its telling it can change the frame of where you are.

In its outer shell—the first of countless—The Way Through Doors is sprung from happenstance eruption. Selah Morse is a municipal inspector, assigned to some contorting version of New York enhanced with the properties of one of Calvino’s many cities, who among his routines sees a girl hit by a car, a violent act effectively jarring the girl’s memory to blankness. Selah then involves himself in the process of her healing: he volunteers himself as a loved one and takes the girl home; there he begins telling stories with the intention of reawakening her recall. This strange tension—a man planting himself in someone else—is that what’s going on?—quickly blooms into a series of stories within stories, people within people, spaces within spaces, until soon Selah, both in leading and being led, finds himself at the center of a story greater than one mind.

“While my dream was still fresh in my head,” he tells us early on, “I constructed a map of my life, using symbols and writing down what I could. Somehow I realized that to write too much would ruin it…. Therefore, what I wrote down were mostly clues as to how to manage the difficult parts.”

What follows then is the magic of the sleep-enchanted book. Rooms connect to one another as if at the whim of nightmare, cataloged with shapeshifting architectures, impossible objects, and replicating time. Selah’s speaking compounds on itself until soon you, too, the reader, are one of the bodies inside the sentences, side by side, among intuitively linked passages that could exist nowhere but in this book.

...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in