There’s no one like Kent Monkman. One can rarely say this literally about fine artists. Great paintings, of course, employ idiosyncratic vantages, styles, and metaphors, but their subjects and insights are seldom peerless. Yet Monkman—a Cree interdisciplinary artist raised in Winnipeg, Manitoba—and his historical, often fantastical paintings stand alone in the art world. His work responds to an education system bereft of Indigenous content, foiling this erasure using artistic, institutional, and commercial means. In so doing, he has become one of the only sources of the kind of cultural news he delivers.

Monkman not only fills a conspicuous knowledge gap for millennial Canadians like myself, as well as the generations preceding us, but does so with pointed ambiguity and figurative complexity. In 2019, he created two enormous paintings that subvert familiar narratives of colonial migration and its legacies, which were displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Great Hall. This drew me to Monkman’s Being Legendary exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum in spring 2023, where I stared for long stretches at various harrowing, playful, and ruminative works, linked by the odysseys of his gender-bending, time-traveling protagonist, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle.

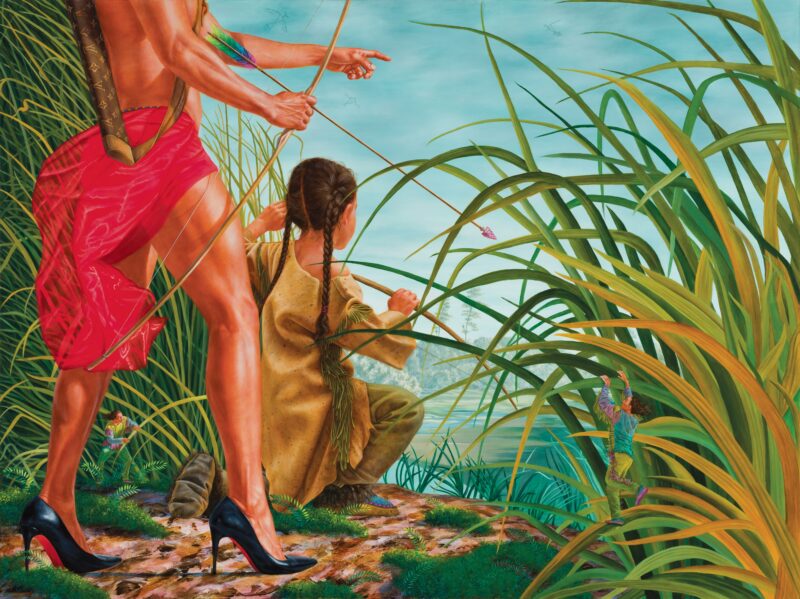

“It’s about giving people sensory experiences they can learn from instead of a fact sheet to read,” Monkman told me when I visited his studio in Toronto’s Eglinton West neighborhood to talk about They Knew Everything They Needed to Live, a painting from Being Legendary. He wheeled out the original for us to contemplate while discussing it. I confess I was so spellbound by its mix of realism and surrealism that more than once I had to forcefully redirect my attention to our conversation.

—Alessandro Tersigni

THE BELIEVER: What really holds my gaze in They Knew Everything They Needed to Live is the juxtaposition of Louis Vuitton, stilettos, and rayon with traditional Indigenous life. The scene seems both historical and fantastical, which somehow makes it feel contemporary.

KENT MONKMAN: That aesthetic comes from the genesis of the character Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. I essentially created Miss Chief to reverse the gaze of nineteenth-century settler painters who made a lot of landscape paintings with Indigenous subjects—like Albert Bierstadt, George Catlin, and Paul Kane—by inserting her into their work. Her presence across time has a very contemporary perspective to it that had to be reflected through what she looked like. I decided she’d be drawn to Louis Vuitton. It’s a French luxury brand that’s been around since the time of the fur trade, so it fit perfectly. Blending contemporary and historical periods is a very Indigenous way of thinking, in many ways. It’s the collapsing of past, present, and future into one time, which is all time.

BLVR: Does this painting itself have an origin story?

KM: This one is in reference to a knowledge keeper I know personally, Keith Goulet, who became a Cree linguist. It’s not supposed to be Keith, but it’s based on his story. He retained his language because he was never forced to go to residential school and grew up in the bush, where he learned how to hunt. Even as a child, he knew how to feed himself. Indigenous children had all this knowledge about how to live and exist here that was given to them by their parents and grandparents. But it was lost in the settler school system, which brought a different way of teaching and different knowledge systems. They Knew Everything They Needed to Live is about learning from our elders. It’s about this very expansive world that was shrunk throughout the colonial period by the extraction of children, which broke up those cycles of intergenerational knowledge. The painting has a tranquility, but that’s a kind of premonition that something bad is going to happen. In the exhibition, the next painting you see depicts the Mounties capturing Indigenous children in a similar landscape. It’s important to not skate over the fact that our world got smaller.

BLVR: I hesitate to ask you to concretize the artwork’s symbols, but how do the petroglyphs and the little people fit into that?

KM: Because this work was shown at the Royal Ontario Museum, the exhibition was very much about comparing Western ways of looking at nature with Indigenous ways of thinking. For Miss Chief to fit into a Cree cosmology, she had to have relationships with other legendary beings. Almost all world cultures have mythical little people, whether they are leprechauns or a whole variety of others. We have stories of little people who are sneaky mischief-makers, known to live near the water’s edge.

With the petroglyphs, the more I looked at them, the more they looked like dinosaurs. Rock drawings of thunderbirds looked more like pterodactyls to me than eagles. That hinted at the fact that, like our elders have always said, we’ve been here forever. Settler theories have generally estimated that Indigenous peoples arrived in North America around ten thousand years ago. While I was working on this show, I discovered the work of Cree-Métis archaeologist Paulette Steeves, who places Indigenous people on this continent roughly sixty thousand years ago to one hundred thousand years ago. That was mind-boggling to me.

BLVR: There’s a geographic idiosyncrasy to this painting that’s eloquent for me as a Canadian: wet lowlands, Carolinian forest, eastern white pines in the distance. Or maybe I’m projecting. Can you talk a bit about Canada as a milieu in your work?

KM: This to me is North America. The border is recent; it’s pretty arbitrary. And so many Indigenous people would have moved around and across it. For foliage, often I’m looking at how other painters paint plants. For instance, these were all based on John James Audubon, an early-nineteenth-century North American botanical painter who painted a lot of birds and their environments. I wanted to have Western science and Indigenous cosmology collide in order to discuss the science that’s embedded in our ways of knowing about all parts of nature, whether it’s star knowledge or plant knowledge.

I don’t really think about the painting as being Canadian, per se, but rather as depicting Indigenous land, whether it’s what is now known as Canada or parts of the United States. It’s really about challenging the myths of those two founding nations, which were designed to serve the settlers’ purpose of occupying and dispossessing, and finding so many holes in them. Most North Americans haven’t been taught these histories.

BLVR: Speaking of education, when I was at Being Legendary, I noticed the museum’s two major Canadian galleries are closed indefinitely: the Eurocentric Sigmund Samuel Gallery of Canada and the Daphne Cockwell Gallery dedicated to First Peoples art and culture. Did that inform your curation?

KM: Basically, we got the First Peoples Gallery closed. That was part of the work. I do that kind of behind-the-scenes heavy lifting at museums. People refer to it as “decolonizing,” which is one way of describing it. It’s about undoing systems that have been set in place for so long that they’re sedentary and continue to miseducate, misinform, and actually cause harm—particularly to Indigenous people, who encounter these authoritative voices telling stories about us that we had nothing to do with.

That was the case with the First Peoples Gallery. The problem is that museums can move very slowly, and you have these career-long bureaucrats who occupy very comfortable positions and are not challenged or forced to change the way things are done. I think there’s so much value in museum culture and the way it communicates to society. You have to bring solutions that are going to move things forward in a joyful and positive way. No one wants to hear that kind of criticism unless you’re able to give them something constructive.

These are all aspects of making paintings like this that people don’t see. As an artist who’s Indigenous, in addition to making art, I have to work hard to bring people to it. Having default audiences is something that many artists take for granted. They don’t have to deal with getting their audience to learn a whole bunch of new things just to enter the work.

BLVR: Does that mean that a viewer who doesn’t do their own research or understand the historical context is a less ideal viewer for you?

KM: No, not at all. My goal is to make paintings that anyone can look at. Regardless of your age, background, or experience, there’s going to be something for you. The layers will come for those who are interested in digging in to learn a little bit more. You’ll have this beautiful, polished, seductive thing on the surface that pulls you in. Then as you start to peel back and work through those layers, you’ll find more and more substance. I think if you can move people, emotionally or aesthetically, to learn, that’s much more effective than getting them to read a news story. It’s just the way we’re hardwired to make connections.

BLVR: There are about a dozen people in the next room busily painting your work on canvases of all shapes and sizes. Clearly, your artistic practice is collaborative in some sense.

KM: It is collaborative, in a way. I’ve created this atelier model for my studio, based on how the old masters worked. As the master artist, I’m directing and conceiving of everything, but you also have to develop systems. It can be a collective process: from the kernel of the idea, through to the pencil sketches, to the reference photo shoots, to the smaller painted studies, and right up to the large finished works. It’s all about training. I have senior painters that teach younger painters, and I have a painting manager. Paintings go into flowcharts. We have formal critiques in the studio at least twice a week. That’s something I’m proud of. I’ve created an environment that’s like a laboratory for experimentation, and trial and error.

BLVR: Does your team of painters have to learn how to manifest your style?

KM: Yes, and that very much became a way of transmitting how I want these paintings to be made. A lot of my painters were actually oil painters, so I’ve had to teach them my approach to acrylic. I use a lot of specific glazing techniques and very thin, transparent layers of paint. That’s how the old masters could create so much depth in their color. I developed a similar technique with acrylic, the beauty of which is that, unlike with oil, those layers dry very fast. A great benefit of working with other painters is that it forces me to analyze what I do and communicate very subtle information about color and method.

BLVR: What about the concepts behind your work? Does your team have input on them? Is it an artistic collaboration as well as a practical one?

KM: It’s really important to have the team informed as to what I’m about, so they can assist me in achieving the maximum effect. Most of the people I hire are artists in their own right and bring their creativity and expertise. I’m talking about the concepts all along, testing ideas on them, tweaking this, strengthening that, and determining if an idea is getting lost. My first audience is here in the studio.

For this series of paintings, we developed the exhibition with the Royal Ontario Museum, and I was in conversation with their curators and interpretive team, who were looking at my images and trying to wrap their heads around the big picture. I really relied on those museum professionals because that’s what they do—they create these experiences for audiences. Through that process, we edited things, added some things, and filled in some gaps.

The point is that I’m never working in isolation. As an artist, I’m really interested in communicating. I know there is a certain kind of art-making that is a little more insular and self-reflective, but why would I want to talk only to a small audience or my own community? The whole purpose of putting all this energy out there is to reach the biggest audience possible.

BLVR: You’re obviously the author of the work, the way a director is the author of a film. But I’m curious: Did you paint any of They Knew Everything They Needed to Live?

KM: Of course. I actually use that analogy of filmmakers or orchestral composers often. The best films are the ones where the director doesn’t have a heavy stylistic hand. They’re just kind of barely there, and everything else is serving the ultimate purpose of that narrative. I feel like that’s something I realized through maturing as an artist. I started as an abstract painter wanting to make my own unique mark with paint. I called it a wiggle. And I found my wiggle, but it becomes a very personal language that ends up leaving your audience outside the work. That’s when I figured out that I wanted a more universal kind of language that reaches a wider audience and disappears my hand. The paintings I’m making in this studio with this team are as much me as anything I’ve ever made. Yes, I can do all these paintings myself. But we can make more paintings as a studio if we train more hands to make them. Also, paintings need time to evolve and unfold. Some paintings take years because you pause, reflect, innovate, and make discoveries along the way that you can’t predict, because they happen by using the medium itself. Working with a team makes more time for all of that.

BLVR: Do you ever use yourself as a model? I get the feeling there’s something of you in Miss Chief.

KM: Miss Chief definitely started out as me. I’m not always the body, but… I don’t want to give away all my secrets! Face-wise, she’s definitely me.

BLVR: How is your work received in the United States? Are Americans getting it?

KM: You know, they’re about a generation behind, I would say, in terms of appreciating Indigenous contemporary art. But they’re coming around. You can feel it happening. They’ve had so many other conversations there, about African American voices and Latino experiences, and the First People have somehow not been considered. I think that’s a testimony to the effectiveness of the American mythology. They were so effective at removal and erasure that, in their minds, native people remained something from the past for a long time. But there are so many great museums in the States that are getting ready for new conversations.