Kati Heck was born in 1979 in Dusseldorf and lives in Antwerp with her husband. Though her work encompasses sculptural installation, short film, and photography, she is best known for her large-scale paintings, which hover between the cartoonish and the realistic. There is often a playful, brutish, humorous, grotesque quality to her work. Currently she is preparing for a solo museum exhibition that will appear at the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo in Málaga, Spain, in 2013. We spoke over Skype several times.

—Makeal Flammini

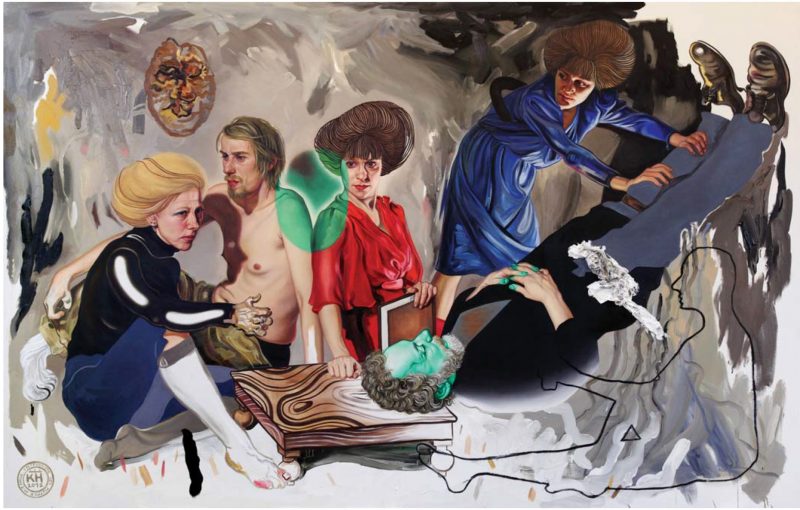

Entführung der Mutter mit Hase

THE BELIEVER: What is happening in this painting?

KATI HECK: This painting involves two evenings and an afternoon. It begins with my friend Jürgen calling to say, “It’s time to pick up the magic mushrooms.” So he, my husband, and two others went to collect them. If you look, you can see in the top left corner there is a drawing of a bus and the four people who went to pick up the mushrooms. I like to give the viewer small things to discover when they come closer to the painting. When they returned they were all so proud, they said they had found the Mother Mushroom, the mushroom that carries twenty times the psychedelic power of all the others. It was really pretty, a green-blue color and quite huge. We were all so impressed. So I hid all of the mushrooms for later.

BLVR: Where and why did you hide them?

KH: In a box in the sleeping room. I was afraid someone would take them, for good reason. One evening our Swedish friends came, which you can see as a turtle and a spider, scratched into the white under where Guy is lying. All the people in the painting came; we had a big dinner, and at the end everyone but myself took all the mushrooms except for the Mother Mushroom. I told them, let’s go to the park nearby, it will be much nicer to enjoy this feeling. So we went, and because my friend and I jog there every day, I know there is this kind of Indian hut.

BLVR: Tepee?

KH: Yes. They were so impressed by this tepee because they thought I had made it for them. There was a child’s playground with a slide, and Guy went down the wrong way, exactly like in the painting. Somehow it seemed to me that if he would go the other way he would go to heaven delivered on a silver platter. It looked like he was dead and being transported.

BLVR: Can you explain the toxic green color his fingers seem to be dipped in?

KH: At the second dinner he stole the Mother Mushroom. You can see between Tina [in the red dress] and Rufus, there is a [green] shadow, also on his face and fingertips. It is meant to show us that he touched and stole the Mother Mushroom.

BLVR: Like stolen bank notes that would explode on you?

KH: We all knew he took it with him. Very suddenly he had to leave. It was funny and very suspicious. At the first dinner, the Mother Mushroom was very beautiful, green and puffy. At the second it changed into exactly what you see above the head of Rufus. It looked like a brown mask, as if it had a pinched face. All evening we looked at the mushroom, comparing it to the photograph of how it had looked at the previous dinner. Suddenly it was gone. It was very clear. He is a collector of the strangest drugs, and he keeps them in a little box. I imagine it is there.

BLVR: What is the strap around his leg?

KH: To make the photograph, the pose was very difficult. It required two large men to hold him upside down on a board that he was bound to with a leather strap.

BLVR: All the people in the painting seem to have the thousand-mile stare. What are they all looking at?

KH: Chris, the woman on the left, is seeing something. The others, they are not seeing anything. They are all off inside themselves.

BLVR: The only person that seems present is you [at the far right].

KH: Yes, well, I am the director. Directing the scene, checking to see if everyone is OK.

BLVR: On Guy’s leg, is there something attached to the painting?

KH: I had such a good time on this painting, thinking about life. I thought, I should let my birds free. I wanted them to shit on my painting. Edvard Munch used to put his paintings in his garden and let the rain fall and the birds shit on them. So I put some food onto the painting, but they would never shit on it. So I soaked toilet paper in oil paint and put it on.

BLVR: Are all of your paintings autobiographical?

KH: Whoever you are painting, I suppose you are making a portrait of yourself. But what interests me most is the situation. I think a lot of times paintings are just general feelings that probably everyone can feel. When things were not going well and we had no money, I painted myself peeling potatoes. I was this person who didn’t believe her hands could work for her anymore. In the end, you can get very sad, though I’ve never cried with a painting.

BLVR: You’ve never cried with a painting?

KH: No. With music you can do it. With painting, it reaches for you and moves you, but not in quite the same way. For example, this painting is quite personal, but it’s also a simple story. Of course, there are many others where the truth or intensity is much larger. This painting—I really like it, probably because there were so many new things happening. I was trying to make a background, which I rarely do, and it was exciting. There is paint almost everywhere and that’s something not so… Heck.

BLVR: What do you mean?

KH: In the past, I’ve always ignored it. I thought if something is in the background, it isn’t important, which is bullshit, of course. I like for all of my people to be life-size, not going back into space. It used to be that I started with the figure, then later I added a bit of background. Nowadays it goes more hand in hand. Maybe I make the face first, because that is something I can trust, and then all the realism starts to bore me, so I start doing things in other places. It grows together.

BLVR: What was the moment you decided to make this painting?

KH: The wonderful evening.

BLVR: Do you see yourself as a documenter of reality?

KH: In some ways I hope you’re right. At the same time I do exactly the opposite. I paint what I see and what I would like to see. I would never paint a cell phone or something, because I don’t like them. It’s my idealistic world, though sometimes brutal things happen in the painting. My neighbor Rik is seventy-five. He has these very white legs with no hair on them. You can see all of these varicose veins. I find it very pretty. I am always checking them out. I think all these ugly things that happen on the body, which people are so easily disgusted by, can be so nice. I am interested in the ugly.

BLVR: When you step back from a painting after it is finished, are you sometimes shocked by what you see?

KH: I never start with the perfect idea of how something will look. It all unfolds as it is happening. I always like the smallest parts, the way a brush worked for me at one moment. On this painting, it’s the red dress.

BLVR: When you start a painting, how often do you work on it?

KH: I wake up, I paint, I take a nap, I paint, I go to bed. If I must, I take a break, but I would rather not. When I paint a face, it takes two days or something. You are spending so much time, you begin to have an intimate relationship with the person. You paint all the parts of someone, even the armpit, and it feels like quite something. If I run into the person while I am painting them, I always feel a bit strange. As if you had a dream about this person and maybe it went too far and you can’t meet the eyes.

BLVR: I notice in a lot of paintings the hands and feet can become so thumpy and grotesque. Is there a reason for this? For example, the foot of Rufus?

KH: I like his foot so much. It’s really because the canvas stopped and I wanted his whole foot, so I gave it a little curl. He is like an elegant ballerina. He could stand up so gracefully with this foot. I paint feet this way because it is joyful for me.

BLVR: How do you choose your colors?

KH: It starts with clothes for me. In an orange dress everything can be involved, from yellow to blue—even purple, which I wouldn’t imagine. I often use green. It’s a magical color.

BLVR: Is it sad to see your paintings go?

KH: Sometimes. Mostly, I am glad. I had to do this painting very quickly for a deadline, and then it was gone, somehow too little time to say goodbye. When it was time for it to travel to the States, I gave a little kiss to each of the people.

BLVR: Where is this painting now?

KH: It’s in a private collection in New York. I think it hangs in an office.