When they first appeared in the Village Voice, in 1956, Jules Feiffer’s cartoons didn’t look or read like anyone else’s, but the expressive looseness of his figures, the characters’ elaborate verbal humor, and Feiffer’s sardonic wit have shaped comics ever since. Feiffer has written movies, plays, musicals, novels, children’s books, and a memoir, in addition to illustrating numerous books, but his first great love has always been the comics he devoured as a child. He wrote about this passion in his acclaimed 1965 book of comics criticism, The Great Comic Book Heroes; his newest book, Kill My Mother, is a noir graphic novel that celebrates what inspired the cartoonist.

—Alex Dueben

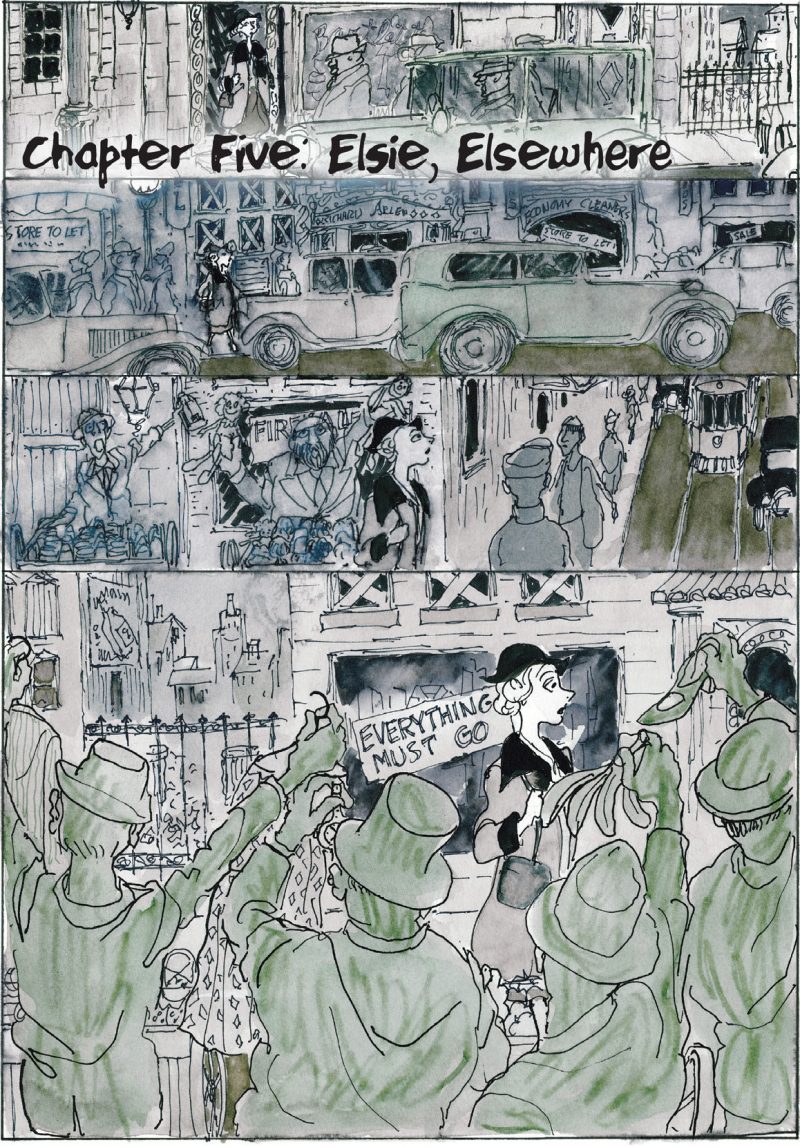

Kill My Mother, 2014

THE BELIEVER: You dedicated Kill My Mother to many of the people who defined noir, but the first name on the list is probably the least well-known. How did Milton Caniff and his comic strip Terry and the Pirates influence you?

JULES FEIFFER: One of the shocks to me—who grew up in the 1930s where Caniff was number one, and the most publicized and glamorized of all cartoonists working at the time—is that in subsequent years, to subsequent generations, even to young cartoonists, he seems to be unknown. He invented so many of the traditions that the form follows. Along with Will Eisner, I consider him the greatest of all the storytellers.

BLVR: I kept thinking about the comic strip, particularly those big Sunday strips, as an influence in terms of how you structured this book.

JF: Oh god, yes. My favorites as a kid were the adventure strips in the newspapers, particularly Terry and Eisner’s Spirit. That was my education. As I read them, I tried to analyze them—not just Caniff, but Al Capp, who I also admired. I was fascinated by the different styles of storytelling used. I was in love with the adventure strips, but when I came of age, it became clear I didn’t have the drawing style or chops or the facility with a brush that allowed me to go into this field.

BLVR: When you say “facility,” you mean stylistically?

JF: I could not draw in a realistic manner convincingly. I could not use a brush—which was then the preferred tool for cartoonists—with any real facility. My style was sloppy. I couldn’t make it look authentic—or the way I defined authenticity, based on the work of the people I admired. The more I tried, the less I succeeded.

BLVR: What changed?

JF: I got to be eighty. [Laughs]

BLVR: Is that all it takes?

JF: What really changed is, all those years, without knowing it, after I began illustrating children’s books—my own and...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in