Several years ago, I asked The New Yorker’s cartoon editor, Robert Mankoff, to tell me about Edward Steed, a recent addition to the magazine’s regular lineup of artistic humorists. “He’s English,” Mankoff emailed back, “twenty-five years old, and anyplace he puts his hat is home—although he doesn’t wear a hat. Last I heard from him, he was traveling in Mongolia. You’re right, he is amazing, a once-in-a-generation talent.”

While Mankoff has since moved on, Steed still contributes regularly to The New Yorker. Born in 1987, Steed was raised in the rural county of Suffolk in eastern England, has indeed traveled the world for work and pleasure, and recently received a US visa.

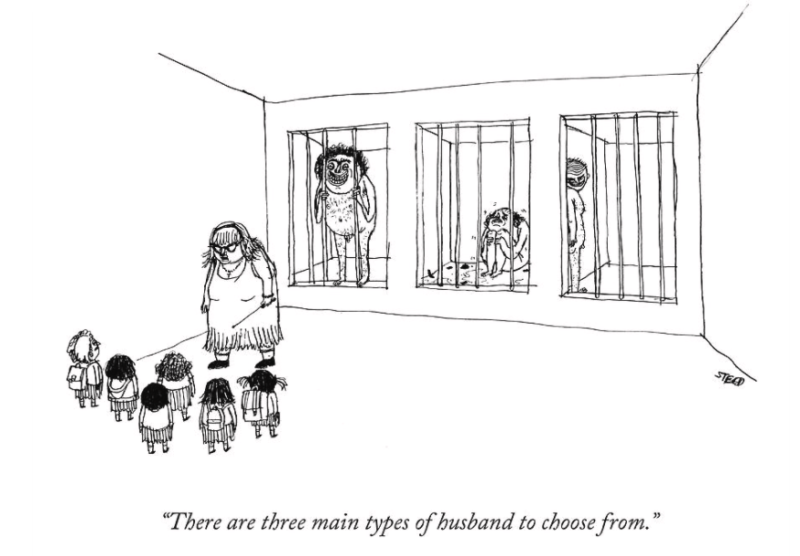

There’s a dark hilarity to Steed’s scratchy drawings, which guide the eye across the image in a puzzle-solving dance, as secondary and tertiary characters grim up the background. For someone who took up cartooning as an adult, Steed draws like an old master (perhaps Pieter Bruegel the Elder). His work is wise, funny, angry, and melancholic beyond his years, and as this trenchant drawing from the May 29, 2017, issue demonstrates, with its disturbing accuracy and multiple foci, there’s really nothing else like it around.

“I don’t feel I’m at my mature style,” he told me one afternoon in the Queens, New York, sublet he was temporarily calling home. “I still feel I’m working it out.”

—Richard Gehr

THE BELIEVER: Why did you choose this particular drawing to discuss?

EDWARD STEED: It seems like a high point of how I’ve been working for the last few years. I can’t imagine writing or drawing this joke three or five years ago. I thought it was great when I drew it, but it doesn’t seem to be particularly popular. It generated quite a lot of hate mail at The New Yorker. Penises in drawings always elicit hate mail, and there are two in this one. I heard from a lot of men’s-rights groups. “So you think all men should live in prison?” they said, and “You think men should live in a zoo?” Ridiculous stuff.

BLVR: How did you come up with it?

ES: For three or four years I’ve been generating ideas in a particular way in order to get to a certain kind of joke. Four or five days a week, ideally, I’ll go to a café in the morning with a stack of plain paper and a pen, and just start making lines and shapes, maybe a face or something, and see what emerges. I start with the visual side of things and try to craft a joke. It probably sounds quite difficult...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in