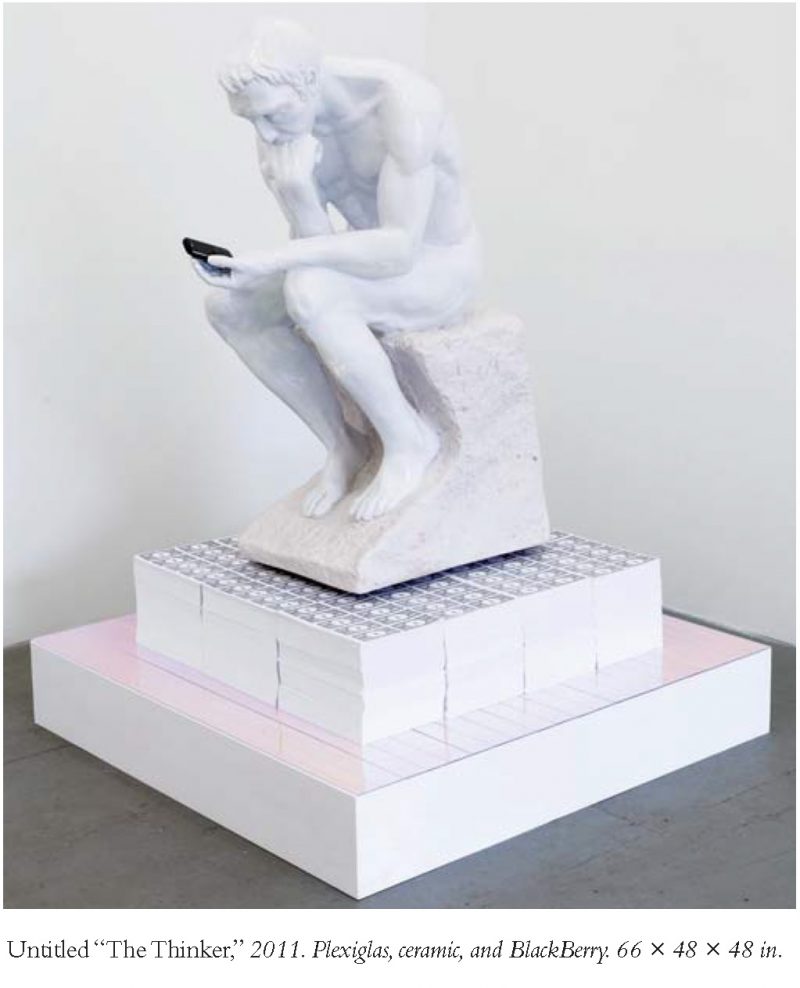

Brian DeGraw mashes up culture. His artwork dances through a spate of forms and references, reflecting a city-dweller’s uneasy relationship with pervasive mass media. His finely drafted drawings depict iconic figures such as Osama bin Laden and Bob Dylan, often merged together kaleidoscopically, and his assemblages appropriate music detritus in ways that recall Christian Marclay—installations of record sleeves, framed collections of song requests DeGraw received while DJing. DeGraw is known as a musician, spinning international urban tracks in New York clubs, and playing his eclectic brew of synths, samples, and drum pads with the psych-jam band Gang Gang Dance. I spoke to him about his sculpture The Thinker, which recently showed at the James Fuentes gallery, in Manhattan.

–Ross Simonini

The Thinker

THE BELIEVER: Is that Monopoly money on the pedestal?

BRIAN DEGRAW: Yes, it is. All ones.

BLVR: What were your first steps in making this piece?

BD: The first step was to find a fabricator to do a replica of Rodin’s Thinker. I needed the left arm of the sculpture to be flipped around from the original, though with the palm turned upright, and that proved very expensive on the fabricator’s end. So I just had them make a version of the original and then I chopped the arm off, cast my own arm in the desired position, and attached that.

BLVR: What was the casting process like?

BD: The fabricated part of the sculpture was cast in marble, and I hacked away at that with a jigsaw, which was very scary, as the material was very aggressive and huge chunks would fly off and hit me in the face and all that. Casting the arm was gentle, though—I just stuck my arm in a long, hollow tube of Alja-Safe mold-making material and let the form take shape, then poured it in plaster, then whittled it down a bit to be the right length for The Thinker.

BLVR: Did you create the piece with a specific motive?

BD: The idea came to me out of observing the obscene amount of cell-phone dependency in the streets. I mean, this is something I am always looking at and amazed by— the lack of attention people pay to their surrounding space when they are deep in text. From that, I started thinking about Rodin’s Thinker and how, if it were made in the modern day, he could very well have been texting, rather then simply staring at the ground in contemplation. When most people are stumped or need a think nowadays, the phone is always part of the equation, so I liked this image of the classic Thinker just subtly updated for the times. From there, this sculpture began to have more of a personality for me. I was imagining this whole scenario where the thinker was a once-very-wealthy businessman, constantly attached to his phone and his numbers and dollars, and then suddenly the collapse of capitalism came and the general population shifted into a morespiritual world society. Currency was no longer of any worth, as the barter system had been put into use. Dollars were worthless now. We were onto hours, timetrading. Good deed for good deed. So this man is left on top of his pile of money, which has turned into nothing more than Monopoly money, and he’s still staring desperately at his phone… looking for answers and wondering how his whole capitalist life fell out from beneath him.

BLVR: Do you consider this image to be a visual joke in any way?

BD: No, I’m quite serious about it.

BLVR: Is art-funny different from other kinds of funny, would you say?

BD: Comedic art is always a little bit tough for me. I think I read too deeply into everything—to the point where I don’t honestly believe that any art is just pure comedy. I always find myself thinking that the humor in certain work must be coming from a place that at its roots may be much less humorous. I think a lot of stand-up comedy is this way, as well. Sometimes the funny social commentary is really dark and heavy on the inside.

BLVR: Would you say this sculpture is similar to your earlier work?

BD: I think it’s similar to some of the installations I made in the early 2000s in the sense that there is a very definite message, but one that is not really forced to be understood by the viewer. I think my approach somehow always ends up in this vein—in both visual art and music. I often wonder what people think my intentions are. I don’t think I ever really make things that are very easy to read, nothing with an obvious punch line.

BLVR: You often use well-known imagery as your source material. Why does this approach appeal to you? Is the process related to musical sampling at all?

BD: I started very early on drawing recognizable portraits of people who exist or have existed in some sense in the public eye. Even when I was three or four I would always draw ET or the guys from Miami Vice, Crockett and Tubbs. I don’t fully understand what the appeal of that is or was to me, except in certain cases when I choose certain people that contribute to the overall idea of what an exhibition means to me. For this past show that was the case. There was a larger sculpture I ended up leaving out of the show because it took up too much space in the room. It’s a giant, threedimensional infinity symbol made of wood that is painted with piano keys, like a never-ending Möbius keyboard. Music played a big part in the theme of this show, in terms of the concept of the collapse of the current monetary system and a return to nature and spirituality. Most of the drawings included in the show are of musicians that I consider to be sort of warriors of this shift, people who have been in touch with this return to nature through their music, people who are sort of sound-tracking the shift by tapping into their true inner spirit—the basis of humankind’s connection with nature and the earth. There are also some nonmusical figures in there: people like Jane Goodall and Osho. And also in certain cases I would simply draw the face of the person who I was listening to on the stereo while making the show, because I am of the belief that everything is connected, so I don’t like to always censor myself in terms of whether a certain image is “relevant” to the theme or not. I put faith in the fact that if something is happening or if I am drawn to something in the moment, then it must certainly be of some relevance, given the cyclical nature of things and the connectivity that I’m talking about. Oftentimes it will be years before that connection shows its face or dawns on me. That is actually one of my favorite feelings in the process of art-making, when the meaning finally reveals itself very clearly to me. I love that. It feels similar to when you meet a person and have a connection with them, but for years and years you don’t actually explore that connection, you just say hello when you see them and you think to yourself, That person has great energy, or whatever, but then somewhere, later in the line of time, your connection is validated through a proper shared experience or a really great long conversation.