We Americans seem to cherish the notion that, as a country, we’re slow to get stirred up but decisive once resolved to act. This is a particularly important part of our national mythology right now, given that we’re throwing our weight around in all sorts of unlikely places for official reasons that started out as tenuous and have since deteriorated in their persuasiveness. Other countries’ civilians are getting killed. Our own people are getting killed. The mess we claimed that we needed to clean up seems to be getting bigger. It’s reassuring, then, to know that Americans don’t rush into things; that we suffer all sorts of indignities to our pride and self-interest before, finally, taking on the mantle of heroism that had been hanging on that peg, waiting for us all along. Imagine George W. Bush recast as young Henry V, for example: the wastrel who’d simply been waiting for his country’s call to allow him to show everyone just how much he’d been underestimated.

This is, of course, one of the central characteristics of the Western movie hero; of the hard-boiled private dick; of the revenge fantasies powering the careers of the otherwise-inexplicable Charles Bronson, Chuck Norris, and Steven Seagal. This slow-to-rile self-control shows up in a surprising number of iterations in our male protagonists.

If you were taxonomizing that figure, you might first divide the type into two basic categories: the Hero in Repose and the Hero in Disguise. Or, say, Henry Fonda in My Darling Clementine and Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca. Both wait to act. Much of the audience’s pleasure, in both cases, derives from that wait, and the satisfaction the audience knows is coming. (Oh, boy, when he finally gets out of that chair…) In the case of the Hero in Disguise, there’s the additional pleasure afforded by the anticipated banishment of the movie’s not very serious doubts that this person was a hero at all. No one in Casablanca—not the wily and unprincipled Claude Rains, or the absurdly principled Paul Henreid, or the harried and lovesick Ingrid Bergman, or even the poor Nazi straight man (Conrad Veidt, not having come so far, really, from his sleepwalking murderer in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari)—is at all surprised when Bogart’s Rick throws self-interest out the window in favor of the underdog and duty. Sure: Rick may talk like an isolationist for three-quarters of the movie. But when the chips are down…

*

That pleasure—of watching the Hero in Disguise step forward to assume his responsibility—is one expertly generated by Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. And expertly critiqued in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist. Both movies are centrally concerned with an ethical question of some current interest to Americans: at what point someone bearing witness to enormous suffering should attempt intervention, however potentially inconsequential or even futile.

It’s impossible to imagine The Pianist’s being made without Spielberg’s movie preceding it. First of all, because of the nature of the industry—who on earth would hand a director as uncertainly commercial as Polanski $50 million for such a subject if there hadn’t been concrete proof of the possibility of a big payday?—but for a more intriguing reason, as well: The Pianist seems—in all sorts of ways but especially in the treatment of its central hero—to be a direct response to Schindler.

Those who’ve seen both might notice the odd persistence with which Polanski’s movie seems to refer to Spielberg’s. Every few minutes in The Pianist we come across directly echoing shots and scenes, some of which derive from shared historical sources and some of which seem designed to acknowledge the movie’s debt to its predecessor. Spielberg renders the night of the liquidation of the Krakow ghetto through a memorable long shot of the ghetto’s windows lighting up with machine-gun and shell fire; Polanski repeats the image in his version of the Warsaw uprising. Spielberg deftly evokes the brutal suddenness of the Polish collapse and German occupation through the economy of his cut from a nightclub party to the drumbeat foot-stomping of storm troopers marching through Krakow; Polanski cuts from his protagonist’s father’s suggestion that “all will be well” to those same storm troopers’ boots, this time parading through Warsaw.

However much he admired parts of Schindler’s List, though, aspects of it must have left a director like Roman Polanski—whose work articulates a worldview implacably grimmer than Spielberg’s—deeply dissatisfied. One of Spielberg’s triumphs was that he’d taken a supposedly unspeakable and unrepresentable piece of history and fashioned it into an enormous critical and commercial success. In doing so, he’d dragged an apparently intractable and hugely forbidding subject into the widest possible swath of public consciousness. Suddenly there was a whole world of people out there who didn’t go to depressing movies and who didn’t want to learn anything about the Holocaust—because who needed to immerse themselves in something like that?—who trooped into Spielberg’s movie, because it was Spielberg and because it was a cultural event, and found themselves confronting, whether they liked it or not, a pretty effective representation, all things considered, of the liquidation of the Krakow ghetto. For that little bit of forced education alone, Spielberg deserves a lot of credit.

But returning to that notion of the unrepresentable: both the extent and the extremity of the suffering in the Holocaust were so insupportably unbelievable that our minds do, in fact, turn away from comprehension in the face of them. We never fully grasp that that many people were exterminated. Just as we never fully grasp what we’re looking at in Alain Resnais’s documentary Night and Fog when we’re shown the way the concrete ceiling of Auschwitz’s gas chamber was torn into by human fingernails.

Any commercial filmmaker faced with material like that—events that may be incommunicable in their own terms—has to use narrative and thematic patterns with some precedent in order to communicate unprecedented meaning.

There was plenty of precedent lying around. The new Israeli state was probably the first to try and find a framework of meaning for the Holocaust, by casting it as a cause-and-effect narrative: catastrophe and heroism. There are obvious advantages, in terms of constructing national myths, in connecting the two: catastrophe creates the occasion for heroism; heroism gives meaning to catastrophe. So the industrial extermination of six million people is linked to a historical sequence of Jewish catastrophes, all of which led to the redemptive birth of the Jewish state. Fair enough, we might think. After all, what’s the alternative, in terms of making sense of this? Total despair? Hatred of God and man?

Except that choices like that have implications. The creation of a narrative is the creation of an aesthetic object, the design of which generates aesthetic pleasure. The creation of a narrative also demands recognizable, in other words, privileged, characters: characters who, for the purposes of the story, are more important than other characters. You see the problem, in ethical terms, of making that claim in the context of the Holocaust.

In fact, as Henry James pointed out, dramatic action almost always revolves around the story of a remarkable character. Which makes the catastrophic/heroic model even more tempting as a way of making sense of the experience. Schindler is heroic. Stern, Schindler’s quietly resourceful and ethically flawless right-hand man, is heroic. They survive.

We have, in other words, in Schindler’s List the most traditional kind of narrative structure, based on suspense, based on the question missing from nearly all nonfictional Holocaust texts, from Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz to Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah: what will

happen next? Will the good guys survive? Repeatedly in Schindler’s List we find ourselves urgently wondering whether a particular character will make it through a particularly horrible moment. And repeatedly our wish is granted, and they do. The stimulation of expectation and the gratification of that expectation is the way commercial narrative structure works.

Everything comes back sooner or later to a satisfying closure. Every family we follow is provided a fate, and every family we follow survives. We’re exhilarated when the guards at the end read off Schindler’s list. It makes us feel—and it’s supposed to make us feel—as if Schindler’s list redeems all the Nazis’ lists.

God knows, Steven Spielberg understands how to produce a pleasurable narrative, and he plugs that expertise into this context. His characteristic moves are often scenes of ironic comic reversal. One is the triumph of the plucky underdog, often a child. (So we see a boy in the concentration camp, ordered on pain of death to rat out whoever stole a missing chicken, fingering someone already killed. And, significantly, not having his brains blown out for his temerity.) Another characteristic move is the seemingly inexorable disaster averted. (What can possibly stop that Great White plowing toward Roy Scheider and his ineffectual little rifle at the end of Jaws? Omigod! The oxygen tank in its mouth blew up! What can possibly stop that German tank plowing toward Tom Hanks and his even smaller pistol at the end of Saving Private Ryan? Omigod! An airstrike!) And what can possibly stop the extermination of all those women whose fates we’ve been following once they’re herded into the gas chamber—one of the movie’s most harrowing moments the first time it’s viewed—except: Omigod! It is a shower.)

Now, part of Spielberg’s achievement involved knowing when to pull off such reversals and how much to mute our impressions of their frequency—since his audience knew the Holocaust was a story mostly about catastrophe not averted. Even so, moves like those must have particularly unsettled Polanski, who witnessed the Final Solution as a boy wandering through Poland, a particularly hellish corner of the European maelstrom at that point, which by all accounts rarely produced the kind of moments we most frequently associate with Spielberg’s work.

So in The Pianist, other elements from Schindler’s List are aped in order to be turned inside out, or exposed. There’s the Little Girl in the Red Coat in Schindler’s List, for example, technologically spotlighted and sentimentalized by that theatrical dab of color that, throughout the chaos of the liquidation, makes the pathos of her dilemma even easier to track in long shots. She’s singled out by her colorization as more heartbreaking, more innocent, first among equals. She certainly seems to strike Schindler that way: when he spots her smudge of red in a pile of corpses later, it’s a moment we’re invited to read as decisive in his conversion from selfish to selfless.

A dead ringer for that same little blond girl pops up in Polanski’s movie, and she’s accorded no more importance than anyone else. The camera glimpses her alone in the crowded and chaotic resettlement plaza, crying and holding an empty birdcage, and never returns to her again.

One of the more famous moments in Schindler’s List depicts the capriciousness of both Nazi cruelty and fate: Levartov, an old man, is taken outside the factory to be shot. The officer’s gun misfires, and we wait, excruciatingly, while he borrows another; that misfires; and finally, the officer gives up, settling for a whack on Levartov’s head before moving on. It’s the kind of thing Schindler’s List does so well: a truly horrifying scene, but one that ultimately delivers what we want.

So in The Pianist a group of Jewish workers are singled out of line, told to lie in the street, and shot one by one in the head. The officer’s gun misfires before he can kill the last man in line. He fusses with it and tries again; it still misfires. He fusses with it and tries again, and shoots the man through the head. That moment alone may encapsulate—and may be intended to encapsulate—the difference between Steven Spielberg and Roman Polanski. And may explain, as well, why Schindler’s List won the Academy Award for Best Picture, and The Pianist did not.

*

The main difference between the two movies, though, involves their protagonists.

We catch our first real glimpse of Oskar Schindler (played by Liam Neeson) seated at a nightclub, cigarette in hand, sizing up the SS men at the neighboring tables, the romantic figure of mystery. Throughout the movie we’ll be delighted with Oskar’s nerve, and charm, and entertained by his swaggering. We’ll stay grateful to him for his ability to continually outwit and stay ahead of the most mythically fearsome figures of the twentieth century—the SS—and their embodiment, Ralph Fiennes’s Amon Goeth. (Schindler and Goeth will be organized for us as alter egos: German angel and German devil. At one point we’ll crosscut between each of them shaving as they prepare for their day: the day of the liquidation of the ghetto.)

Spielberg’s Schindler exudes style and a suavely ironic charm. He seems to be all about jaded self-interest and yet betrays persistent glimmers of warmheartedness. He’s one of those Heroes in Disguise, we quickly register; we’ve been raised on the type. Slowly but steadily, more goodness peeks through. So we’re encouraged to enjoy and forgive his charming and shallow selfishness, if not exploitativeness, in the first half of the movie—Jeez. He has a harem?—on the grounds that he’ll eventually become the traditional hero we want him to be.

Those historical aspects that diminish the real-life Schindler’s heroism are muted or eliminated. The real-life Schindler was, apparently, an agent of the Abwehr—German intelligence—which partially explains his nerve and his miraculous power. That’s dropped, which makes his standing up to people seem cheekier and more satisfying. It also allows the audience to avoid mixed feelings as to just what he was up to. His principal interest to historians has always centered around his ambiguity as a heroic figure; it’s never been clear exactly why he did what he did, or how he should ultimately be viewed.

In the film, however, all doubt is resolved. By its end, Oskar’s not only a hero, but a hero who helps, by his individual action, redeem the ugliness of mass genocide, a slaughter organized by one state, abetted by a number of others, and passively accepted by nearly all the rest.

Oskar’s heroism is meant to counterbalance, in other words, that much suffering, that much complicity, that much active evil. So the movie has an investment in significantly elevating his stature. Which begins with casting an actor the size of Neeson, who towers over everyone else he sees.

This idealized Schindler’s movie, then, shifts tones between the two modes attendant upon the catastrophic/heroic model: the ironic and the didactically monumental. There’s irony all throughout, of course. But there’s also a surprising amount of the monumental. There’s Oskar in a long shot, like Moses, leading all the women he’s saved from Auschwitz back to their factory. (The real Oskar apparently sent one of his women to trade sex and jewels for his Jews’ lives. Which doesn’t have quite the grandeur of this version.) This Oskar has so much stature that in his address to the labor camp guards after the war’s ended, he dares them in his calm, booming voice to carry out their orders to murder everyone in the camp. His bluff isn’t called, and Ben Kingsley’s Stern—the disapproving Jew who becomes Schindler’s second-in-command—and a few others widen their eyes with relief and admiration, communicating to him and us that he sure is one ballsy guy.

*

Since Jews can no longer run businesses, Oskar comes to them with a proposition: he’ll run it; they can do everything else, and once the war is over, their investment will revert to them. Presentation is what he announces he can bring to his first deal with the Germans. It’s what the deal can’t do without. He calls it “a certain panache.” It’s not simply window-dressing; without it, the deal can’t exist. He’s not just a good salesman; he’s a good salesman whose work involves screening off the ugliness of what the deal represents.

The deal, as Schindler proposes it, works like this: Jews put up the capital. Other Jews provide the labor. Stern manages the operation. So then what exactly, Stern acerbically asks him, does Oskar contribute? Well, he answers, not at all embarrassed, he provides the spectacle, he provides the charm, he provides the style. He promotes the hell out of the enterprise. And that’s a pretty important task, considering that we’re talking about slave labor inside an enforced ghetto that is being slowly liquidated. And we know Oskar can do it, because we’ve seen him do it before. The purpose of the opening sequence at the nightclub, in fact, is to take him from unknown to legendary on the basis of show, of bluff: from “Who’s that?” / “I don’t know,” to, as the maître d’ says, “Why, that’s Oskar Schindler!”

Film critic David Thompson was the first to point out what must have been for Steven Spielberg a grand analogy between himself and Oskar Schindler: that a manufacturer of basic enamelware, a man who considered himself all presentation, might yet save his soul with “the gift of life.” Schindler is dedicated to presentation and knockout effects. He’s a showman; he’s elusive at his core; he’s hugely successful. He sounds a lot like the way Spielberg has always been presented in the media. Schindler in the end proves he’s more than shallow; he proves he’s profoundly good. Most importantly, he does so through his ability as a showman. Oskar Schindler may have been the first protagonist of Spielberg’s with whom he could closely identify. And Oskar won him his first Academy Awards for Best Director and Best Picture.

*

It’s Spielberg’s version of Schindler who sells the Holocaust to us. It’s his version that makes the Holocaust viable as a mainstream blockbuster. Most of us will watch the catastrophic as long as we’re given the heroic along with it; otherwise we consider it too depressing. And Oskar’s deal allows us to foreground the heroic and the uplifting. He allows the movie to pull off an amazing sleight of hand: to be a feel-good movie about the Holocaust that still comes off as unflinching and brave. This is because Oskar acts, and acts with near-complete success, even in a situation in which the odds are so overwhelmingly against him. Like all our Heroes in Disguise, he knows what to do, and he does it.

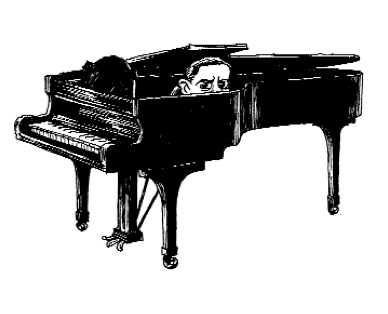

His counterpart in Polanski’s The Pianist is another historical figure—Wladyslaw Szpilman, celebrated enough for his talent to be a cultural celebrity in his native Poland by the outbreak of the war. As presented to us by Polanski and Adrien Brody, Szpilman is a smoothie: calling out “Where’ve you been hiding her?” to a friend about a beautiful woman he’s just met, as explosions rock their building. (One detonation flattens some people just behind him on the stairs, yet he continues off screen in pursuit of an answer, never looking back.) He’s incompletely successful at hiding the pleasure his power of celebrity affords him while he’s running flirtatious circles around the wide-eyed Dorota, the beautiful blonde who will later, with her husband, provide him shelter. He’s blasé and slightly foppish, sleek, and finicky in his tastes. There’s an odd self-satisfied quality to his gracefulness. His narcissism is, in fact, commented on periodically. Having arrived home safely after the outbreak of hostilities in Warsaw, he tells his brother Henryk, who’s fiddling with the radio, that his music show has been taken off the air. As though at the outbreak of World War II, Henryk’s major preoccupation with a radio might be in seeing whether he can pick up one of his brother’s performances.

In the movie’s opening scene, Szpilman, in a recording studio, refuses to stop playing despite his engineer’s departure and direct hits on the building, until he’s blown off his bench by a shell. But the refusal comes across more as a mulish preoccupation with his music than defiance or courage.

So whether we’re aware of it or not, we start hoping that he’s one of those Heroes in Disguise. For two and a half hours, though, he persistently frustrates that hope. He’s not especially brave or virtuous. He’s a watcher, a reactor, and his recessiveness is one of his most remarkable traits, not only early on, but even at the end. He’s like a wraith witnessing the ruin of his city and the annihilation of his people. The movie, in fact, continues to make a note of his periodic refusal to act, a refusal that, as luck would have it, doesn’t cost him his life. As Warsaw is being attacked, his parents prepare to gather up their family to flee; Szpilman halts all that by announcing that he’s not going anywhere; if he’s going to die, he’ll die in his own home. His statement seems more petulant than intrepid. The same thing happens a few years later, when he’s hiding out: his contact arrives breathless and desperate to inform him that the Gestapo is almost certainly on the way. Again Szpilman says he’s not going anywhere. In fact, he stays in that apartment until the building is blown down around him by the Wehrmacht.

Every so often, he teases us with the possibility of a conversion to hero status. He goes to the printer of the underground paper in the Warsaw ghetto and announces he wants to help. The printer tells him with a laugh that musicians don’t make good conspirators, and Szpilman drops the subject. Well. There’s persistence for you. When Majorek, one of the architects of the rebellion, lays out his plans for the uprising—tells him they’re about to begin a battle to the death—Szpilman responds, “If you need help, I…” and trails off. A few scenes later he finds Majorek asleep on his bunk and whispers that Majorek’s got to get him out; he’d rather take his chances on the Polish side than stay there any longer.

To be fair, he’s by no means entirely inert. He helps talk his brother out of custody. And for a short while during his last days in the ghetto, he’s an active part of the gun-smuggling efforts in preparation for the uprising. But most of the time, he doesn’t act or even sound like much of a hero. When one of his Polish benefactors expresses her admiration for the Jews’ courage after the failed uprising, he asks her only what good it did, and seems unpersuaded by her answer.

In direct contrast to Oskar Schindler, for nearly the entire movie, Szpilman doesn’t know what to do, or when to do it.

So how does he survive? Why does he survive? Luck, mostly. The movie’s relentlessly dispassionate tone continually insinuates that survival in the midst of an entire society organized to destroy you requires some mixture of single-minded determination and luck. Heroes, of course, have both. But that’s not all they have.

*

One of the quietly radical things about The Pianist is just how little its protagonist is allowed to do. Mostly, while we watch, he wears down. He hides. We see him sleeping. Fretting. Poking around for food. Trying not to make noise. Staring into space. Every so often he grieves. (Or seems to; it’s often hard to tell. He does weep once.)

Mostly, he witnesses things. And yet we need to remember that, like most of his compatriot Jews in Poland, he spent a large amount of time during the early war years in denial. (Surely the Germans aren’t looking to exterminate the Jews. And even if they are, surely the Allies wouldn’t let that happen. Etc.) He’s a witness because of who he was; he’s also a witness because this movie is more skeptically self-conscious about its whole enterprise: the whole project of making, and watching, a movie about horrors like this.

Consider how much of this movie is viewed through windows. Through windows, from a fixed and limited perspective, the pianist watches these people perish, and history go by. For long, long stretches he’s wordless, just gazing upon what’s going on. Sometimes he’s bored; sometimes he’s moved; sometimes he’s mesmerized; sometimes he has to work to figure out what’s going on. Does his position sound familiar? It should.

From their window, the Szpilman family watches the theater of other people’s arrests. The Germans dump an old man in a wheelchair out the window, then shoot his relatives in the street. Szpilman has a front-row seat for that, and, somewhat implausibly, for both the 1943 ghetto uprising and 1944 Polish uprising (One apartment turns out to look over the wall into the ghetto, from which he can watch the Jews’ increasingly hopeless struggle; another is across the street from Gestapo headquarters, from which he can see the first Polish assaults on their tormentors.)

Both of which leave us and him experiencing a bizarre, You Are There version of history. Everything, for all its verisimilitude, feels faintly staged. (Come with us now and witness history from inside the very center of events…)

*

We are continually made to feel slightly self-conscious about witnessing. At a street crossing in the ghetto, Jews held up by traffic are forced into a ghastly and impromptu dance by a few bored and playful Nazi soldiers. The sequence, like so many others, with its helplessly restricted vantage point, plays like a circus of horrors viewed by someone shackled to his or her seat. Yes, yes, yes: the Nazis were sadistic ringmasters. But behind them, of course, as was the case with Schindler’s List, the filmmaker is the real ringmaster, indulging in this aggression, theoretically in the service of education. And as the coaches of our sports teams never tire of suggesting to us, the pain that makes us stronger should not, then, be attributed to sadism.

Both Spielberg and Polanski relied on the documentary footage generated by Nazi filmmakers. As Polanski remarked in an interview about the footage of the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto, “It’s easy to forget that there’s someone behind the camera, filming all of this horror. Deciding on the most effective or pleasing way of presenting it.” And so in his movie we linger on a shot of a three-man SS camera crew filming Jews, filming us.

There is, in fact, a famous literary antecedent of active witnessing, even within the Holocaust: Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl. Frank’s book became the ubiquitous school text precisely because of the way her fierce desire to work through the implications of what was happening turned the enforced passivity of her position into something heroic. Anne Frank didn’t just sit around all day; she did her best to work stuff through, ethically, philosophically, metaphysically: however she could. Did Szpilman? We have no idea.

It’s important, in terms of our good feelings about Oskar Schindler, that he not only decisively come around to the cause of heroism, but that he demonstrate, in some carefully selected ways, remorse about his earlier self. The historical Schindler stayed matter-of-fact and jovial to the end, according to witnesses. Spielberg, notice, will not allow him that. Spielberg has him break down, a ruined but saved man. And all the Jews he saved, especially the women, surge forward, wrapping their arms around him to confirm his status not only as hero, but as a hero who has nothing whatsoever for which to blame himself. Schindler, meanwhile, is inconsolable, but it’s hugely revealing what he’s inconsolable about. He fixes on his gold Nazi party pin and laments that it might have saved two more Jews. And we think, wait: now he’s blaming himself for having spent too much on presentation? He only got as far as he did on presentation; the movie’s been drumming that into our heads for three hours. But that may be the only charge on which the movie, to the discerning viewer, has absolutely exonerated him.

And what sorts of things is he not beating himself up about? How about not having gotten started a little sooner? The historic Schindler was, clearly, humane, and

heroic. He also may have been hedging his bets: it hadn’t taken a genius after the Nazi defeat at Stalingrad to register that Germany was going to lose the war; it was just a matter of when and how. And Schindler did most of his good deeds nearly two years later—after the Allied invasion of Europe had already succeeded.

Or how about the harrowing unfairness of the list itself? Schindler resolves to spend what money he can muster to save as many Jews as he can, by buying them back from the SS. Stern, when they’re drawing up the list, holds it before him the way, in popular representations of Moses, Moses holds the tablets, and says, “The list is a complete good.” And that’s an assertion the movie urgently wants us to accept. The list is, in fact, such an awesomely huge good that it’s not hard to accept the claim. But a complete good? We should give a moment’s consideration to the moral ambiguities we’re being spared at that point. What it would mean to draw up such a list? Imagine: You have great news. You can save a tenth of your family and friends from certain death. Isn’t that great? Now draw up the list. And now imagine everyone you’ve had to leave off, after the list’s been drawn up, responding only, The list is a complete good.

They draw up the list. Whoever’s on it will live; whoever’s off it will almost certainly die. No attention is devoted to the difficulty of choosing. Because we don’t have to choose. Everyone we’ve cared about has made it onto the list. And when those saved hurry to their trains, the camera is careful not to pan away to the less fortunate.

*

Szpilman, meanwhile, isn’t undergoing any conversion experiences, or, most of the time, emoting much of anything. In fact, like two of Polanski’s greatest earlier movies, Repulsion and The Tenant, The Pianist slowly turns out to be about being stuck in your own head and going quietly nuts because of it. Part of its point is to allow us to see this elaborately—and slightly smugly—civilized man reduced to an emaciated animal state. And the pathos in that regard is so intense that it starts to tip into comedy, as when, toward the very end, he hangs on to that oversized can of pickles wherever he goes with all the hopeful credulity of a Beckett tramp or Charlie Chaplin.

Given what history has chosen to unleash on poor Szpilman, the heroism that’s generated derives from the miracle that anything human survives at all. And not from a version of some kind of crucible-created Clark Kent.

While he’s surviving, Szpilman is also recording, for us, but only recording. As one of the movie’s producers, Gene Gutowski, said about him, “The Germans had cameras, but Szpilman was a camera.”

Well, no matter how taciturn they are, our heroes are not cameras. John Wayne’s no camera. Gary Cooper’s no camera.

And it was exactly that aspect of Szpilman that critics complained about. David Denby in the New Yorker groused that the movie didn’t attempt “to open up the hero at all. Is he ashamed, defiant, guilty? Grateful for his luck? We haven’t a clue. His survival is an anomaly, a mistake, a joke—and that may be why the story appealed to Polanski.” Peter Travers in Rolling Stone identified the fact “that we never get inside Szpilman’s head” as “the film’s nagging flaw. The script, eager to avoid glib posturing, denies the character fullness.” The movie, he goes on to conclude, “lacks the heroic heft of Schindler’s List.” Exactly.

*

We don’t want to judge Szpilman, and we have no right to. The central question of what makes a survivor, and how one does survive in such a situation is a question suffused with ambivalence and guilt for the survivor himself. The Pianist doesn’t even let us take too much refuge in Szpilman’s artistry as a source of solace.

What we might call the Matthew Arnold Model of Consolation, applied here, would go something like this: In the heart of this ruined city, on this ruined continent, a German officer playing Beethoven and a Polish Jew playing Chopin kept this tradition of music, this flowering of European culture, alive. Szpilman survives to play music, ergo the humanity of the cultures that created the music is not lost. His art has saved his life, in more ways than one.

All of that seems to be true. But the movie makes the issue of his artistry discomfiting by reminding us how often he’s spared because of his status as artist, as opposed to his art itself. He’s treated as though he’s more worth saving than others, as something of a special commodity, a special case. Yitzchak, the Jewish policeman who pulls him from line during the selection—and countless others who help—seem to feel that way. Dorota later tells him while he’s hiding out that all sorts of people—in dire straits themselves, of course—have been giving generously to help him.

Some part of those of us who partake in the arts wants to believe that Rembrandt or Picasso are in some ways more important human beings. And The Pianist confronts us with the implications of that desire. The publisher of the underground newspaper rejects Szpilman’s tentative offer of help by reminding him that he keeps the people’s spirits up; he does enough. But we shouldn’t forget, either, that the movie never shows us anything like that, and the movie also has his brother Henryk accuse him, instead, of contributing to his people’s apathy, and of making his way by playing only for rich parasites.

For a movie that centers on a musician, there’s surprisingly very little music used. (It’s certainly instructive to compare its soundtrack to Schindler’s List’s.) Szpilman, alone in one of his hideouts and constrained from making a sound, sits at a piano. We hear the Chopin trapped in his head. It continues while we cut to snow falling outside on the street; then it fades, abruptly. There’s some beauty still present. But it’s mostly imagined, and truncated. Barely surviving.

The music in his head is all he has to live for, now. It’s an amazing thought, when you consider it. When Hosenfeld, the German officer who saves him, first asks him what he does for work, Szpilman says, “I am—I was—a pianist.” When he asks what Szpilman will do after the war, Szpilman answers that he’ll play the piano.

Part of what bothers us about Szpilman is that before, during, and after the war he’s not just an artist devoted to his art; he’s also something of a figure for narcissistic isolation, and it’s narcissistic isolation that finally underpins voyeurism. Until the end of the war when Hosenfeld asks him to play, he’s alone, observing horrors through windows, hearing music in his head.

If Schindler’s List provides reassuring fates for all of the characters for whom we’ve been induced to care, The Pianist doesn’t provide anyone’s but Szpilman’s. Even the fate of its German angel, its Oskar Schindler counterpart—Captain Hosenfeld—is handled with a flat offhandedness. In Spielberg’s world, such heroes are given their due: solemnly memorialized by the entire cast, which returns, out of costume and out of character, after the illusion of the main story has ended, to accompany the surviving historical figures—the surviving real people involved—to each set a rock upon Schindler’s grave. In Polanski’s world, such heroes are swept away. Hosenfeld turns up in a Russian POW camp; he asks a Pole to contact Szpilman; Szpilman returns to the site, a now-empty field. Two title cards then inform us of Hosenfeld’s name—which we didn’t know until then—and that he died in a POW camp in 1952. Did Szpilman ever do any more to try and save him? We have no idea. He says he did, in his memoir. Polanski does nothing with that claim.

That’s not an omission based on a lack of knowledge. It’s an omission that reminds us that the Holocaust is a story primarily about the unsaved. Szpilman means well. He’d like to help. Every so often he even tries to help. But it’s all so overwhelming. And part of the reason it’s all so overwhelming is that such an enormous number of people did not act.

Mostly Szpilman wants to be left alone to do what it is he does. Great artist or not, he’s more an image, in other words, of who we are than of whom we’d like to be.

The music he heard in his head he performs, at the movie’s end, on a concert grand with a full orchestra. He’s alive; civilization’s alive; those survivals are miraculous. The movie ends as the members of the audience rise to give him a standing ovation. The final sound we hear is the applause of an audience that’s so grateful to finally hear this music, an audience of which we are also members. It’s as though his life has come full circle. It’s as though he’ll carry on as if unchanged by everything that’s gone before.