We Americans seem to cherish the notion that, as a country, we’re slow to get stirred up but decisive once resolved to act. This is a particularly important part of our national mythology right now, given that we’re throwing our weight around in all sorts of unlikely places for official reasons that started out as tenuous and have since deteriorated in their persuasiveness. Other countries’ civilians are getting killed. Our own people are getting killed. The mess we claimed that we needed to clean up seems to be getting bigger. It’s reassuring, then, to know that Americans don’t rush into things; that we suffer all sorts of indignities to our pride and self-interest before, finally, taking on the mantle of heroism that had been hanging on that peg, waiting for us all along. Imagine George W. Bush recast as young Henry V, for example: the wastrel who’d simply been waiting for his country’s call to allow him to show everyone just how much he’d been underestimated.

This is, of course, one of the central characteristics of the Western movie hero; of the hard-boiled private dick; of the revenge fantasies powering the careers of the otherwise-inexplicable Charles Bronson, Chuck Norris, and Steven Seagal. This slow-to-rile self-control shows up in a surprising number of iterations in our male protagonists.

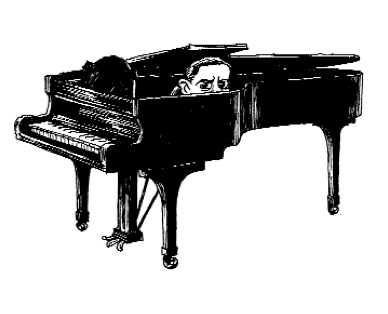

If you were taxonomizing that figure, you might first divide the type into two basic categories: the Hero in Repose and the Hero in Disguise. Or, say, Henry Fonda in My Darling Clementine and Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca. Both wait to act. Much of the audience’s pleasure, in both cases, derives from that wait, and the satisfaction the audience knows is coming. (Oh, boy, when he finally gets out of that chair…) In the case of the Hero in Disguise, there’s the additional pleasure afforded by the anticipated banishment of the movie’s not very serious doubts that this person was a hero at all. No one in Casablanca—not the wily and unprincipled Claude Rains, or the absurdly principled Paul Henreid, or the harried and lovesick Ingrid Bergman, or even the poor Nazi straight man (Conrad Veidt, not having come so far, really, from his sleepwalking murderer in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari)—is at all surprised when Bogart’s Rick throws self-interest out the window in favor of the underdog and duty. Sure: Rick may talk like an isolationist for three-quarters of the movie. But when the chips are down…

*

That pleasure—of watching the Hero in Disguise step forward to assume his responsibility—is one expertly generated by Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. And expertly critiqued in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist....

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in