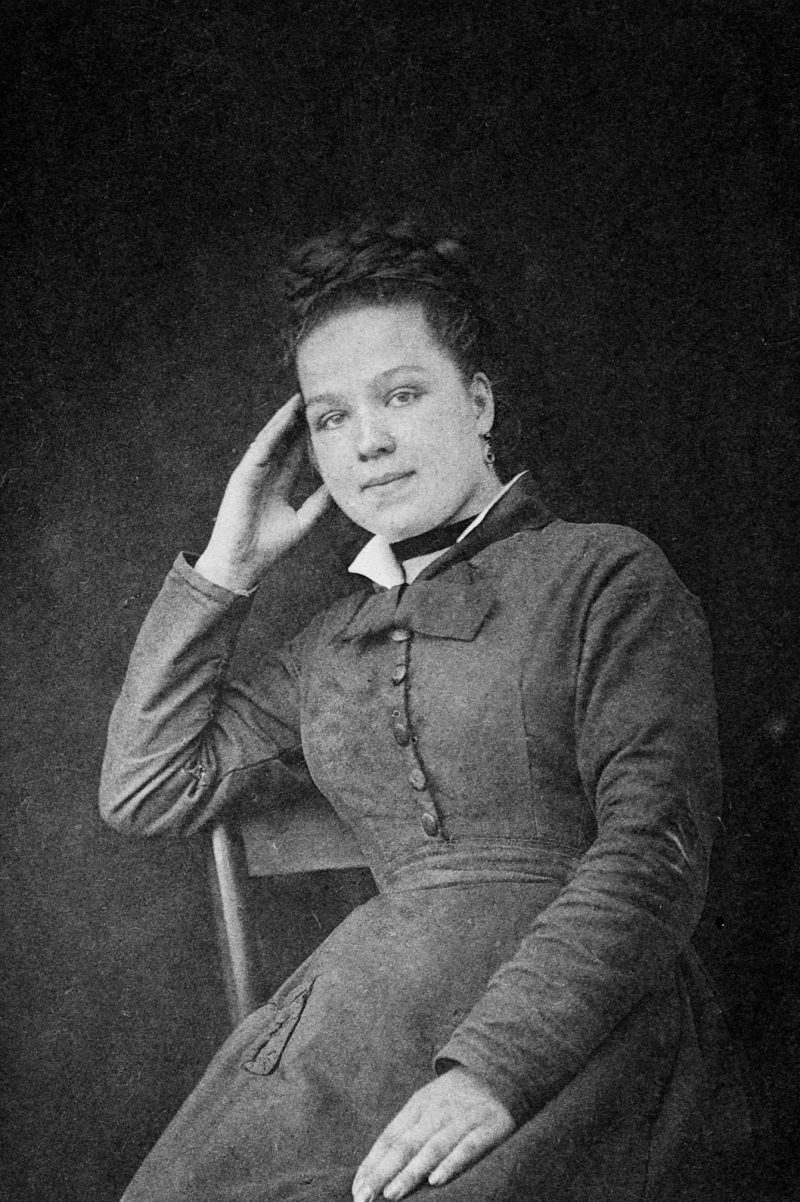

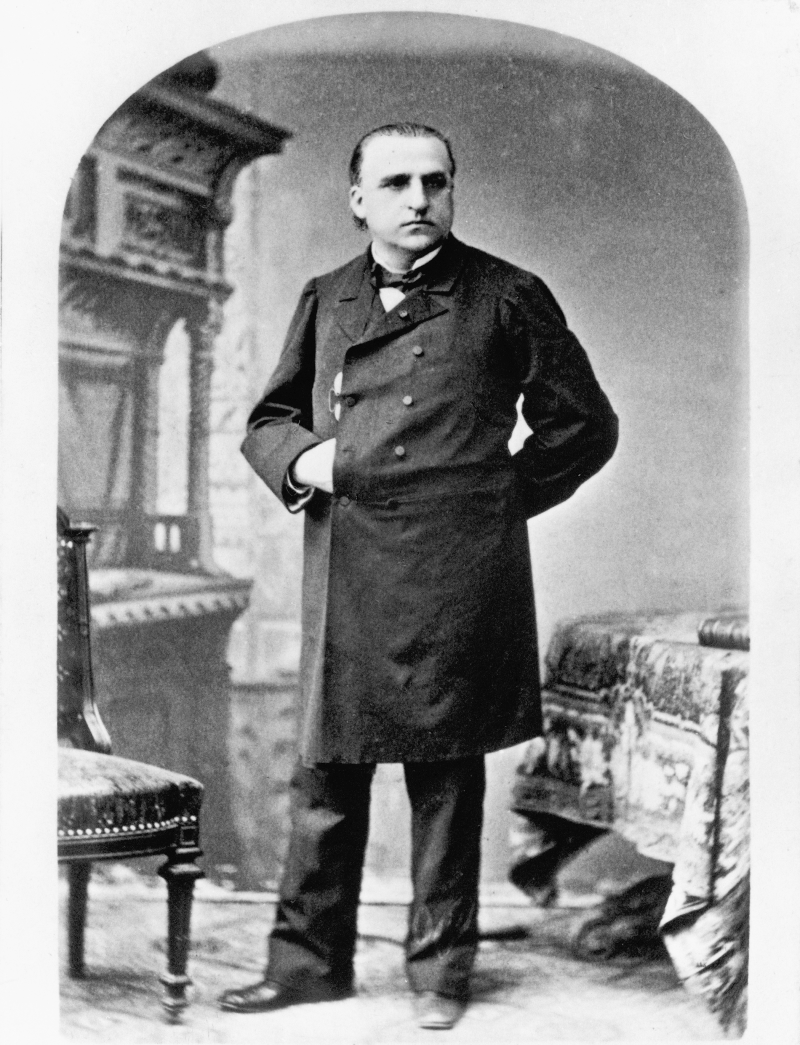

During the 1870s in Paris, three young women found themselves in the hysteria ward of the Salpêtrière hospital, under the direction of prominent neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. Over the course of the decade, Blanche, Augustine, and Geneviève became medical celebrities, their images disseminated through a series of volumes called Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière. Every week, eager crowds arrived at the hospital to attend Charcot’s demonstrations, where his most famous hysterics acted out their symptoms for crowds of medical students, physicians, artists, writers, actors, and socialites. The Salpêtrière became a popular place to visit, even a destination for tourists. At the time, hysteria was a fascinating spectacle that invoked science and religion, medicine and the occult, hypnotism and theater, subject and object in ways that blurred the boundaries between research and art.

*

I first came across the Salpêtrière photographs when I was a graduate student in French at NYU. I was writing my dissertation on a late-nineteenth-century novel, The Future Eve by Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. At that time hysteria was a fashionable topic in literary theory, and was viewed, at least partly, as an illness of being a woman in an era that strictly limited female roles. Blanche, Augustine, and Geneviève, in other words, exhibited symptoms that physically illustrated their actual social conditions, bodily metaphors for their stifling social demands, aptly expressed by paralysis, deafness, and muteness.

Hysteria may be an illness of the past, but the medical and ideological notions of femininity that lie behind it offer insights into the illnesses of the present and the way they are perceived. And while modern medicine no longer talks about hysteria, it nonetheless continues to perpetuate the idea that the female body is far more vulnerable than its male counterpart. Premenstrual syndrome, postpartum depression, and “raging hormones” are among the more recent additions to a medical mythology that is centuries old.

Thus I began with a preconceived notion: that hysterics were victims not only of their home lives but of a misogynist medical institution led by the tyrannical Dr. Charcot. And yet the more I read, the more I found myself admiring Charcot’s brilliance. I also became a reluctant fan of some of the members of his coterie, a group of physicians who worked with him at the Salpêtrière. Instead of a clear-cut world of exploited women and exploiting men, I entered a realm of collaboration between doctor and patient that was far more nuanced.

*

In 1852, the twenty-seven-year-old Charcot spent a year of his medical internship at the Salpêtrière Hospital. The Salpêtrière, the name of which...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in