What we’re seeing here, in a sense, is the growing, the birth pangs of a new Middle East.

—Condoleezza Rice

We should go to the Arabs with sticks in hand and we should beat them on the heads; we should beat them and beat them and beat them, until they stop hating us.

—Israeli taxi driver, quoted in

David Shipler, Arab and Jew.

1. Into The Levant

Moments ago they closed a street in Jerusalem. The police came and unspooled red tape and wire as cars backed up Jaffa Avenue. They wore heavy vests and carried big guns, but they were laughing. Two storekeepers plugged their ears. There was a small explosion. Someone had left a bag sitting in Ben-Yehuda Plaza. This is one part of Jerusalem.

At Mike’s Place in West Jerusalem the tables are outside and a breeze cuts through the courtyard. I play pool with my friend Maimon who lives here now with his wife and child. We met at a ski resort in Colorado eight years ago. I was hitchhiking under a full moon and the white glow of the mountain tops when Maimon stopped to give me a ride. I got a job bartending at the top of the gondola lift, and Maimon taught snowboarding lessons, and when we weren’t working we zipped down the mountains. Those were endless days, where the only thing that mattered was the depth of the snow.

But that was Colorado, and this is Jerusalem, where Jesus died and Mohammed rose to heaven and the Jewish Temple stood for a thousand years leaving nothing but a retaining wall where the Hassidim knock the brim of their hats and kiss the bricks and leave notes and prayers for their God. The capital of a nation at war.

Maimon tells me a story about his time in the Israeli military. It was a time before we met.

“I was in the infantry,” he says. “We were in Gaza, sixteen years ago, and they were launching mortars at us. We saw where they were setting up, spotted them in our planes. They were in an orphanage. I fired at them, but it was night. I shot with an M60, which is a nineteen-pound machine gun that fires 550 rounds per minute. Do you understand what I’m saying? I had coordinates, but I couldn’t see anything, and I was firing on an orphanage.”

From the bar we head to the Wailing Wall and I leave a note on behalf of a friend and I kiss the wall. I should perhaps make my own wish for the war to end but I’m not a believer. We are close to the Via Dolorosa, where Jesus fell carrying the cross he would be nailed to, and we can see the gold dome of the Al-Aqsa mosque. The old city, with its ancient walls and cobbled roads and armies of the devout singing and muttering in the dark, is perhaps the most beautiful place on earth. We stay there, bathed in history, and I forget about the orphanage Maimon had shot at. I will go to Gaza soon, twenty-eight miles long and surrounded by an electric fence. All I need is a press card.

Today, when I go to get that card, they don’t want to give it to me. The press woman says, “What is the Believer? I have never heard of your magazine.”

“The Believer is a big magazine in America,” I say. “OK, maybe not that big. It’s a prestige publication.” I ask her if she would like a copy and she looks through me with hatred. Finally I prevail upon her.

When I am leaving, I say, “Have a nice day.” I kind of want to ask her on a date. I don’t know anybody in Israel except Maimon. She says, “I will not have a nice day. Fourteen Israelis have just been killed in Lebanon.”

A Hezbollah spokesman says the soldiers were “burned alive in their tanks on our land.”

2. North Toward Disaster

Israel is a democracy and a friend and has every right to defend itself from terror.

—George W. Bush,

May 18, 2004

Lebanon is a democracy, and we strongly support that democracy.

—George W. Bush,

March 4, 2005

History has proven that democracies don’t war.

—George W. Bush,

March 21, 2006

It’s quiet in the town of Qiryat Shmona in northern Israel, or it’s very loud. This is the largest town in Israel’s north, and when the rockets land, the ground shakes. Then nothing. Everything is very tense. Sometimes the rockets are incoming but usually Israel fires west to the border. The town is practically empty. The stores are closed except for one, and I stop there and have a beer with a clerk who is watching Keanu Reeves in Speed.

Many of the residents here have moved to a camp on the beach fifteen miles north of Gaza. The Israeli army is taking heavy casualties, or more than they expected. The Lebanese are faring much worse. In 2000, the Israeli army pulled out of Lebanon unilaterally after eighteen years of occupation. Earlier this year they also pulled out of Gaza. They’re building a wall to block out the West Bank and steal some land in the process while creating new facts on the ground as the settlements grow. The leaders of Israel say they don’t negotiate with terrorists, but it looks like you have to negotiate with your enemies. A nation can’t negotiate with itself. Those that thought it could, myself included, have been proved wrong.

I walk at night watching for the flash of tank muzzles. I see a woman smoking a cigarette, her dog nearby. She doesn’t pay any attention to the missiles falling. A handful of lights are on in the windows. A couple of cars parked, the rest of the spaces empty. I stay in the military hotel near the bus station and a soldier steals my computer while I sleep.

The next day, at 5 p.m., all of the photographers leave the kibbutz hostel in Au Goshrim. I ride in an armored car with them. We pass a field where a missile has struck, leaving a crater and a small fire. There are tanks, troop carriers, D9 demolition vehicles. The D9s are horrific machines with giant steel shovels on the front and thick round bars surrounding their torsos in a cage. All of it built upon the frame of a tank. We drive up the hill.

We come upon a military installation but the officers won’t let us inside. The entire north, they say, is a closed military zone.

“They’re not closed,” Uwe1 says. He’s a big, bald, ruthlessly ambitious photographer from a major agency. He likes to argue and hopes the war will go as long as possible. “They don’t have the papers. They’re just not letting us in. They don’t know what they’re doing. They don’t give a shit about us.

“The other night they showed us the bodies of Hezbollah fighters. They were wrapped in plastic bags, and they had their guns next to them. They were like hunting rifles. I said, ‘Hey, these guys are giving you trouble? C’mon.’’’

We cross another gate, into the border town of Avivim. There is a Lebanese village half a mile away but it is empty. I want to cross the border. “No way, man. Everything is booby-trapped.” I ask Uwe for his jacket and helmet, but he just laughs and spins the car around. We can see the minaret of the mosque in the rear window. I feel like we could go over there. Talk to people. Find someone. I don’t trust Uwe’s judgement. Avivim is deserted, too, but there are still a couple of people around.

“I’m too young to die,” Uwe says. “And I love my life.”

We continue through the rocky countryside. It’s beautiful here but also very hard. Past artillery and the occasional ambulance. This is the land of kibbutzim, Israeli idealism, communal farms. We wind up the hills along the border. There is smoke in the distance. It’s so empty and quiet and then loud all at the same time. The quiet of war.

We pass another missile smoldering in the earth. We hear explosions then pass the bushes just set to burn. We can’t get back inside Avivim so we take a dirt road through the back. There are giant tank guns pointing at us when we exit the woods but the gunners just smile and wave. Some of the soldiers rest on the ground, heads leaning against knees. Soon, though, we are turned around and it takes an hour to get back because all of the roads are closed. Then there is small arms fire coming from the Lebanese side. Then machine-gun fire from the bluff above us. We stop, surrounded. The cannon bursts are continuous now. There is another village across the valley floor and fire and smoke there. The sky is blue and purple.

We sit. The only car in the road. It’s nearly dusk. I ask myself what I’m doing, but I know what I’m doing. I’m heading into danger hoping to understand conflict and war and the price of land. Maimon said I was crazy to come here, but he’s already served two tours in the Israeli military.

Finally, we pull out carefully, back the way we came again. There is a great cloud of smoke from behind a Lebanese hill. We drive to a plateau and park and get out. There’s a TV crew there. Massive gunfire, shelling. Soon there are more photographers watching the smoke and the movements.

“They’re bombing a new village,” Uwe says.

Two helicopters hover in the sky above us. The helicopters drop flares like flaming shit from pigeons, hoping to distract the Lebanese missiles by drawing them to the heat. Then we see a plane in the distance and realize it is what the helicopters are protecting.

The plane, everyone thinks, is carrying the new bunker-buster bombs delivered express by the Americans. Now all of the cameras point to the sky.

In the distance two more villages burn. Or maybe they are the same ones. “You see all the helicopters and missiles,” Uwe says. “I think they’re really flattening those villages.”

The hills are filled with Whir! Bang! and Boom! But here in the Upper Galilee, way up high in the strategic position, it is hard to tell the human story contained in that smoke: the families huddling in shelters, trapped children burning to death, others crushed by beams, cut to ribbons by the glass of exploding windows, entire families incinerated. Four hundred Lebanese have been killed so far, sixteen hundred wounded.

This is a part of Israel, the rocky sliver of land between Syria and Lebanon, that has always known fighting. In wars with Syria in 1948, 1967, and 1973. In 1970, a school bus in Avivim, on the northern border, was attacked. Nine children and three adults were killed and nineteen children were permanently crippled. In 1974 three members of the Popular Front For the Liberation of Palestine, which was based out of southern Lebanon, snuck into Qiryat Shmona with directions to take hostages. Instead they entered a housing complex and killed all eighteen residents.

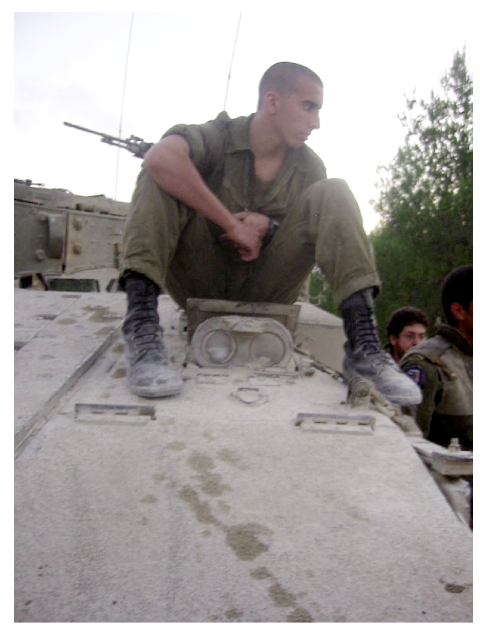

We leave the plateau, again through woods. Up higher, we come upon a tank unit. Two soldiers loading the gun. Another soldier resting on the hood.

The soldier on the tank is from Canada, and we talk a bit about the difference between Israel and America. “You have to be in the military here, so you appreciate your country” he tells me. “We’re doing a good thing and we’re going to change everything.”

“Do you think so?’’

“I hope so. We lost five soldiers out of our group. My friend lost both of his legs, and we got him out in the tank. There are only fifty soldiers in my unit, so to lose five is a lot. The guys that are dead, I want to visit their families because

I know them. But I can’t because we’re at war right now.”

“A soldier stole my computer this morning,” I tell him. “I was staying in the military hotel. It was plugged in, sitting on top of the refrigerator. Somebody came in and stole it while I was sleeping.”

“A soldier is like anyone,” he tells me. “A soldier also steals.”

*

Two days later I get stuck in an apple orchard on the Lebanese border with Uwe while waiting for Israeli troops to return. I decide to leave. I walk out onto an empty road between two checkpoints, each nearly three miles away. I realize I am walking alone on the border and I could be shot and there would be no return fire. It’s my first taste of the fear.

On the day when at least twenty-eight Lebanese are killed by an Israeli bomb in an apartment building in Qana, a hundred missiles rain on Qiryat Shmona in Israel. Four missiles fall near our hotel and a reporter from Haaretz is taken to the hospital with shrapnel wounds. He had been interviewing someone whose house had been bombed when another bomb fell on the building next door. The firefighters around Qiryat Shmona are out spraying the fields. There are six injuries in Qiryat Shmona, and property is destroyed, but nobody dies because the town is nearly empty and those that stayed keep to the shelters.

The Lebanese who died in Qana were in shelters as well. Terrified, innocent. They thought they were safe. But Israeli bombs are stronger, and Lebanese buildings are weaker, and the building collapsed, and everybody perished, and the pictures are all of dead babies covered in dirt and stone. When the building collapsed in Qana, the gears that were turning toward a settlement ground to a halt. The Bush administration had sought to give time to Israel to finish its operations, and the bomb was American-made. The president speaks of victory for democracy, forgetting that Lebanon is a democracy. He links the war in Lebanon to the war in Iraq. But the war in Iraq was a mistake and has already failed. After the disaster, the prime minister of Lebanon says there can be no negotiations without a cease-fire. So Condoleezza Rice cancels her trip to Beirut.

An aid worker says I shouldn’t write about the Israeli side. She says there is no Israeli side because their suffering is nothing compared with that of the Palestinians and the Lebanese. I think she has lost perspective.

As the Israelis push deeper into Lebanon, the Lebanese missile fire focuses on the Upper Galilee, the northernmost point of the country. Shaba farms is here, just a few kilometers from the city. Shaba Farms is a tiny, fortified hillside taken from Syria during the Six-Day War in 1967. According to the United Nations, Shaba Farms belongs to Syria, and Israel keeps it, waiting for a treaty. But the Lebanese say it belongs to them, and Hezbollah says it will fight until every inch of Lebanon is liberated. So when Israel withdrew unilaterally in 2000, Israel kept Shaba Farms. There are people who joke the war with Lebanon is over three acres and a goat. There are others who say that if Israel had pulled out of Lebanon when the PLO left for Tunis in 1982, there would be no Hezbollah. But nobody knows, and nobody believes that if Israel left that small, fortified hillside, Hezbollah would just go away.

At a kibbutz near the border there is a pond and a small field filled with deer. Soldiers back from Lebanon lie around the water, clips removed, rifles slung loosely over their backs. There are signs warning to beware of the animals. A deer was born two weeks ago. They named him Katusha, after the rocket.

When the first rockets fell near my hotel this morning it felt like the walls were going to break. We ran to the porch, saw the blackened field, the smoke rising, fire on the hills, and also smoke coming from where we couldn’t see, to the west.

Safed is twenty miles south and was hit the hardest of any Israeli city in the beginning of the war. This is a holy city, thousands of years old, supposedly founded by a son of Noah and certainly dating back to the Romans. It’s the center of Jewish mysticism, kabbalah. Madonna was here recently, swimming in the purifying waters. Like the Upper Galilee, Safed is mostly empty. There is still a guard at the coffee factory, but coffee isn’t being processed. He shows me where the missile came through the roof into the third floor. “I would have been standing right there but I was on my break. I was playing Sudoku.”

From the roof of the factory we can see the scorched hillside near the hospital. The hospital’s windows are broken and tops of buildings are smashed in places. I meet a man who has just returned. He talks to me about the fear. “You’re playing Russian roulette walking in the streets,” he says. He says they have a safe room in their house. “You shouldn’t be here. If you hear a whistle, find a wall and stand behind it. If you feel something, be careful.”

I meet Jonas, an American Jew who has decided against leaving. His son brings me a twisted piece of rocket that landed nearby. Jonas wants to know what I’m writing about, what my angle is.

“I’m antivictim,” I tell him. He invites me into his house and we talk about fear. He says the rockets started falling on the same day the walls of Jerusalem were breached in ancient times. He says today is the anniversary of the death of a famous scholar and that normally there would be ten thousand people here.

“We were fasting, and when we broke the fast, we set up a table outside, and a rocket came and exploded when it touched the top of a tree only twenty feet away. The tree saved my life. You don’t know,” he says. “You don’t know if it will land here or in the valley or in Haifa. We seem safe sitting here, but we’re not safe.”

“Listen,” he says. “There was a woman. She was six months pregnant, but she went into labor early. She goes to the hospital. When she comes home, her house has been destroyed. You see: it was a miracle.”

It’s getting late and I decide to return to the north. Jonas invites me to stay but I don’t. Jonas says, “They want to push us into the sea. They will wait and wait…”

There is danger everywhere but it is nothing compared with the images broadcast from Lebanon, entire cities reduced to piles of rock. Some argue that what matters is who started it. Others say it is a disproportionate response. Everybody wants to feel safe but that isn’t what people are fighting for. Hezbollah is not fighting so the Lebanese will feel safe, and neither is Israel for the Israelis. Wars aren’t often fought for self-interest. They’re fought for pride, out of fear, for revenge. The fighting in Lebanon is unlikely to make Israel safer. But a person has to believe there is a way out of the bomb shelter and into the fresh air. Jonas didn’t think so. He thought the Arabs and the Jews would always be at war. I mentioned Jordan and Egypt, but he didn’t think that counted for much.

*

After five days in the north, I make it back to Tel Aviv. My pants and shirt are still caked in Lebanese dust from where the tanks and Caterpillar D9s turned over the earth. The beach in Tel Aviv in the evening is warm and peaceful. People here don’t really feel what is happening closer to the border. This is the secular heart of the country, where people drink and dance and swim in the ocean, and nearly everyone speaks English. There are sex shops and parties and nothing seems to have slowed down. I sit at Mike’s Place, an outdoor American bar that was blown up once by a suicide bomber several years ago. Maimon meets me when he gets off work. We are too late when the tow truck comes and snatches Maimon’s car. It only takes seconds for the bars to slide beneath the chassis and hoist the car in the air. Maimon screams at the police officer, pulling on his own hair.

“You have another job for me?” the officer asks. “I’ll do something else.”

I’ll go back to Jerusalem tonight and soon to Gaza and other places. I’ve given up trying to make sense of anything here.

III. The Forgotten War—Into The Gaza Strip

The day before I’m supposed to go to Gaza, I ask an Orthodox Jew at a bus stop where I can find a synagogue. His name is Michael and he invites me to come with him to the Wailing Wall—it happens to be the anniversary of the destruction of the temple. Michael hasn’t shaved in three weeks. Jews are supposed to suffer to help themselves remember. Some people put dirt in their shoes.

On the way, we stop at a demonstration. They’re protesting the forced removal of the settlers from the Gaza Strip. They wave orange flags, and some have orange strips tied to the end of rifles.

Michael tells me I’m not half-Jewish. “That’s like being half-pregnant. If you’re mother’s not Jewish then you’re not Jewish.” I feel rejected. “C’mon,” Michael says. “I didn’t invent these laws. Do you think I don’t want to eat pork?”

We talk about the temple and Al-Aqsa mosque. Michael says when the temple is rebuilt, we’ll all live in peace. “We all believe in one God,” Michael says.

“But you’d have to remove the mosque to rebuild the temple,” I say. “Where Mohammed rose to heaven.”

“No. We would just move it. It’s not even their holiest place. It’s only their third-holiest place. They pray with their backs to the temple.”

“It’s hard to imagine the Islamic world being OK with moving Al-Aqsa,” I say.

“It’s hard to imagine a wolf and a lamb,” Michael replies.

I think about Michael and the endless war on my way into Gaza. When the temple is rebuilt there will be peace on earth. It’s not something I believe, but religious extremism has risen on all sides of the Israeli conflict. I think about Maimon, whom I saw later that night. We were in the old city, filled with Orthodox Jews mourning the temple. We met an old friend of his on her way to the wall. Maimon whispered to me after she passed, “She’s not Orthodox. She used to fuck.” Maimon got his papers the other day. He’s being called up for military service even though he’s forty years old.

Most people aren’t thinking about the war in Gaza since everyone is focused on the war in the north with Lebanon. But 175 Palestinians were killed in Gaza in the last forty days.

Gaza is a hard concept to grasp without going there. It’s barely twenty-eight miles long and four miles wide. There are 1.4 million people; it’s the mostly densely populated place on earth. One million of them are refugees from the Israeli War for Independence in 1948, or what Arabs refer to as al-Nakba, or the Disaster. About 860,000 of those still depend on the United Nations for food. They are citizens of no country. The crossing to Egypt has been closed. The port for imports and exports has been closed. The crossing to Israel has been closed. All of Gaza is surrounded by an electric fence. Journalists and humanitarian-aid workers are the only ones who can get in and out. Until a year ago, a third of Gaza was dominated by Israeli settlements, and to protect the settlers there were heavy restrictions on movement inside Gaza. It could take a full day to travel the twenty-eight miles between Gaza City and Rafa.

In Gaza, Hamas has risen to power, displacing Arafat’s corrupt Fatah organization. Like Hezbollah, it’s part of the government but also maintains a separate militia. The foundation of both groups is Islamic extremism. But there are also many differences. Hezbollah is Shiite, while Hamas is Sunni. There is little reason for Hezbollah to exist, but Gaza is still completely controlled by Israel and has been for the last forty years.

When I arrive at the border there are three buses. America and Germany are taking their few citizens from Gaza to the Jordanian border. Everyone with a foreign passport is leaving. They laugh at me going in. “We should kidnap you,” one of them says.

I walk a long, quiet tunnel built for processing thousands. There are steel beams and giant cement pylons. A large gate opens at the end, and I step into a chamber. The gate closes behind me, and another opens. Sunlight scatters inside through holes in the roof. I pass a restroom covered by razor wire. Then I hear Arabic music and step into the Gaza Strip.

Ashraf2 is there to meet me. “You look good!” he says. “You took out your earrings, and your haircut makes you look like an Arab.”

“That’s because an Arab cut my hair,” I explain.

“Don’t tell anyone you’re American,” he says. “People here don’t like America anymore.”

In Gaza, the dominant features are poverty and destruction. We pass a destroyed bridge over a ravine that will flood when the rains come in the winter; houses will be reduced to rubble. There are some cars, but there are also carts driven by horses and mules. Posters of men surrounded by guns are taped on all the buildings. The men have died recently and are celebrated as martyrs. We pass the settlements the Israelis left just a year ago and destroyed on their way out. We pass a distillation pump donated by Italy, crowded with Palestinians waiting with jugs.

“Nobody can drink Gaza water,” Ashraf says.

I visited Gaza in 2001, and at the time it seemed like things couldn’t possibly get worse. But things can always get worse. Gaza is the graveyard of optimism.

If you ask where the current round of destruction began, the Gazans will say it began with the death of the Ghalia family, killed by Israeli artillery while on the beach near the Erez crossing, where I came in. Israel denied that its ordnance was responsible, but human rights groups have displayed fragments of a 155-mm Israeli artillery shell. Many Israelis believe that only militants are killed in the fighting. They are naive. They don’t believe in collateral damage. War is nothing if not mistakes. The image of the surviving child, Huda, captured the world’s imagination for a few days and the imagination of the Gazans for much longer.

The Israelis say the conflict started with the election of Hamas, whose militia continues to launch Qassam rockets across the border. The rockets are small, but they do damage. They terrorize the population, and eight Israelis have died. More important, the Israelis believed when they pulled out of Gaza and unilaterally left the settlements that the militants would cease their attacks. But they were wrong, and this has infuriated the Israeli public, who feel like they have given something and gotten nothing in return. But the Gazans, who don’t control their ports or crossings and have no international representation, don’t see what they have to be so excited about.

At the hospital in Rafa the head surgeon sleeps on a matt on the floor. “There were nine martyrs today,” he says, lighting a cigarette, trying to wake up.

“There were also twenty-three wounded,” the surgeon says. “Today I amputated four extremities. We fear there will be more martyrs because of infection. We suspect the IDF attacks again tonight. Always we fear at night.”

Leaving, I notice even the hospital walls are covered with posters of the men who have been killed.

Mosher Al-Masry is thirty years old, a member of parliament, and the Hamas spokesman in Gaza. We meet in his apartment in Beit Lahia, a particularly hard-hit suburb just north of Gaza City. There is a sitting room in the front and a curtain to prevent us from seeing the women in the rest of the house. He is well dressed, with a nicely trimmed beard.

Mosheer tells me it is just the Israeli media that says Hamas refuses to recognize Israel and that Hamas has always been willing to negotiate. This is a lie, but I let it pass. He tells me, “America should correct the policies of its government. They will be more welcome in the world.” He’s just a kid with a beard, I think. I mention that the charter of Hamas calls for the destruction of Israel. Mosheer waves his hand and smiles. He offers me an orange soda.

At night I sit on the Mediterranean, on the patio of a hotel called Al Deira. This is where the richest people in Gaza meet. They wear Western clothes. Women sit at tables with uncovered heads. There has been no alcohol since the last bar, the UN Beach Club, was burned to the ground less than a year ago. Among the patrons are a smattering of foreign press documenting the tragedy playing outside—second-stringers covering a war forgotten since the hostilities with Lebanon to the north. Also here are the leftover foreign aid workers. But there are almost no foreign aid workers left in Gaza, and there are less than a hundred people sipping strawberry juice and smoking narghiles, talking, and listening to the sea.

I sit with Hamada, the Gazan head of a major UN organization. His office was destroyed several days ago during a riot that erupted to protest the UN response in Lebanon. “The people you see here,” he says, “they are here every night.” It’s like the deck of the Titanic after the last lifeboat is gone.

With its beautiful beaches, Gaza was once thought of as a potential tourist attraction, but all the other hotels are empty. There is only Al Deira, which costs $80 a night. Ashraf offered to let me stay in his apartment for free, but the water doesn’t work and there are only six to eight hours of electricity. I was hoping to save some money since the Israeli military stole my computer, but when Ashraf told me

I would need to keep away from the windows and only open the door if I heard my name, I decided I would stay in the hotel.

Hamada’s foreign counterpart has left Gaza already, like everyone else. I tell him I met a sick man earlier who was dying and had been waiting more than a month to leave for Egypt and get care. We talk about the impossibility of a targeted assassination. “There are four thousand people per square kilometer. There’s no such thing as a targeted killing in that dense a population.” We talk about the crowding and poverty, twenty people living in one room with no basic sanitary functions. There is sewage running through the streets of the refugee camps where the majority of people live.

“The main problem of Gaza,” Hamada says, “is access.”

We talk about the import/

export zone, which has been closed. There was a project to grow vegetables in the hothouses bought for the Gazans by the World Trade Organization. The hothouses were bought from the settlers, and after the settlers left it looked like the project would succeed. But when it was time to export the vegetables, the port was closed, so the tomatoes sat on the dock rotting.

We talk about the phone calls. In the past months, the IDF has taken to calling people and telling them their homes are going to be destroyed. Often in less than ten minutes. The problem is that this has led to prank calls. “My neighbor got a phone call,” Hamada says. “‘We’re going to bomb your house.’ We didn’t go home for three days, there was no way to verify.”

Then there are the sonic booms. Ehud Olmert has vowed that as long as Qassam rockets are coming from Gaza, the Gazans will not sleep. When there are no troops in Gaza, planes fly over and break the sound barrier. The noise is incredible.

To highlight the animosity between the Palestinians and the Israelis, Hamada tells me about the Beit Leah Wastewater Plant. “The plant contains two million cubic meters of raw sewage in a lagoon. The plant is not working because of the lack of electricity. To make matters worse, the Israelis bomb the lagoon to prevent absorption. If something isn’t done soon, the plant will overflow. If the plant overflows, it will flood an entire neighborhood. The flood will cover 450 houses. The only thing to do at that point will be to push the sewage into the sea, which will kill all the fish.”

I imagine 450 houses two stories deep in shit. I wish they served alcohol here. But when we talk about solutions, Hamada disappoints me. He talks about the right of return, which states that all the refugees from the 1948 war should be allowed to return to Israel. It’s the kind of idea suggested by people who are not looking for a solution. Most of the homes and communities they would return to have long since ceased to exist. Hamada tells me that Israel provokes all the intifadas, that the Qassam rockets are just firecrackers. But in fact, the Qassams have destroyed homes and claimed lives. More important, the Qassams are a provocation.

The problem here is that a Gazan intellectual with a good job with the United Nations cannot see the part his own people must play in any solution. History, Israel, the United Nations, the Arab nations—particularly Egypt—have created a welfare state and an echo chamber. This echo chamber is oblivious to news coming in from the networks and the internet. People don’t trust information from the outside world because most people don’t know anybody from the outside world. Here, in response to the seizure of a Palestinian militant in Jericho, rioters destroyed the British Council, where people could get job training and borrow books. Here, in response to the war in Lebanon, they destroy UN offices even though the UN is the only real employer left and is responsible for feeding and housing more than half the population. Hamada doesn’t see the role the Palestinians have played in their own misery: the kidnapping of the soldier, the election of Hamas. In this way, he’s no different from most of the Israelis I’ve met who blame all of their troubles on Arabs. I let Hamada pay for my juice.

I lie awake in the middle of the forgotten war. There is some gunfire in the streets, or perhaps just fireworks from a nearby wedding. I watch CNN and the current death statistics filter across the bottom of the screen followed by news of the doping scandal in the Tour de France. I ask myself, if stuck in this cage and unable to make contact with the rest of the world, what would I do?

In the morning, Ashraf and I have breakfast, then I wait for him in his apartment while he goes to mosque. When he gets back, I ask what he heard, and he responds that the preaching concerned America and the evil use of American power. Driving through Gaza City, Ashraf points at the destroyed buildings and laughs, “American-made! You make very good bombs. Look, they go through six floors. It’s amazing.”

After the head of Hamas, the most important man in Gaza is John Ging, head of UNW-

RA, the UN organization founded in 1948 to deal with the Palestinian refugee population. He’s the only person in Gaza who seems willing to criticize the Hamas government. But then his office is giant and air-conditioned and he can leave when he wants to.

“The tragedy is, after all this time we still feed 860,000 refugees in the strip because they don’t have the means to feed themselves. With the recent incursions, we’ve added 100,000 to our rolls. Donor assistance has been cut off since March, when the Palestinian Authority under Hamas control didn’t meet donor requirements. There are no garbage trucks to pick up waste, for example. We’re at the relief end, providing the very basics. We have four schools at the Jabalya camp that we’ve now filled with fifteen hundred people seeking shelter, running from the Israeli military. This is the first time the Israelis have cut off power, so things are much worse. The sense of imprisonment is heightened. Anybody with the option to get out is already gone. What the Palestinians don’t understand, when they launch their rockets at Israel, is that the damage might not be the same but the fear is the same. People get distracted by the magnitude of force. Israel should rein in its military. The PA, which is run by Hamas, has the responsibility to stop the Qassam rockets, which are being launched by Hamas. Hamas can form a legitimate government but there cannot be a separate military wing that exists outside of the government. They also have to recognize Israel and recognize existing agreements.

“Over the years, there’ve been so many false starts. We see a flicker of hope, most recently the settlements leaving. We thought we would now move on to economic development. But it didn’t happen.”

John provides me with contacts to facilitate visits to refugee camps and meet families whose homes have recently been destroyed. I see the schools and the rooms filled with mats. Each room sleeps roughly fifty people, with separate rooms for women and men. Many have lost homes near the Israeli incursion zone, the homes destroyed for strategic reasons.

I hear about the phone calls, parents running with their children and eight minutes later their houses destroyed. One family explains how their house was bombed two weeks prior. The only grown-ups in this family are women and

a very old man. The women’s brother was killed over a month ago. “And then they shot the cow,” they tell me.

“What?”

“After the Israelis bombed the house, they shot our cow.”

I decide to leave Gaza after a couple of days. The suffering is the only story here. Or is it? Before I go, Ashraf shows me the universities, and I understand at least one thing: the rise of Hamas.

There are two universities, Azar University and Islamic University. Azar University was founded by Fatah. Islamic University is at least unofficially affiliated with Hamas. Azar, like Arafat’s organization, is old and decrepit, the buildings in disrepair, despite the fact that it is newer. Islamic University is pristine and orderly. This is why Hamas is in power in Gaza. Under Fatah, a tenth of the population was employed by the government, but the police wouldn’t stop the most basic crimes. But Hamas runs clinics, and their security forces are effective. Islam offers structure in a place that knows only war. Hamas did not come to power because of their position on Israel. They rose on the backs of inefficiency and corruption. The idea that Hamas can be forced from power by starving Gaza is a false one. Hamas is the power here, they control the message. There is no one else to negotiate with.

IV. Leaving Israel

My first night back in Jerusalem, I go to a gay bar with a gay Orthodox rabbi and others who have arrived in Jerusalem for the gay-pride week coming up. He asks me what I think of the idea that Islam doesn’t work because it was founded on success while Judaism and Christianity were founded on failure. “Well, it’s not true,” I say. “At least for the Shiites. Anyway, I don’t think you’re getting at the heart of the problem.”

The rabbi and I watch the performers, a transvestite burlesque.

“I love this,” he says.

“I wouldn’t mind doing that,” I say. The tall black woman is shaking her hips, lip-synching “I Will Survive.”

“Are you good with makeup?” he asks.

“No,” I reply. “And I twitch. My mascara would be everywhere.”

We watch the show and dance until midnight, when the rabbi leaves. He has to be up early. There’s an interfaith meeting. He’s hoping to spread tolerance and acceptance for gays in the religious community.

On my last day in Israel, Maimon and I meet back in Tel Aviv. I want to tell him about the third side of the conflict, the one simmering in the West Bank, the land between Jordan and Israel. Israel has built a security barrier separating East Jerusalem from Ramallah and Bethlehem, cutting off 40 percent of the West Bank economy. I want to talk about the giant settlements like Maale Adumin, built between East Jerusalem and Ramalah, with forty thousand residents already and forty thousand more expected in the next few years. I want to tell him I visited the Tomb of the Patriarchs, where Abraham is buried, father of the Arabs and the Jews, and how you could feel the pain of the conflict simmering in the streets of Hebron and the small settlement there and in the square in Qiryat Arba named in honor of Baruch Goldstein, who slaughtered twenty-nine Muslims while they were praying in 1994. It’s a small country, but these are all places Maimon has never been. I want to talk about the conflict and the history and how hard it is keep the story together when there are so many threads.

But when Maimon sits down, he looks very serious.

“I ordered a pitcher,” I say.

“Good idea,” he says. Then he starts to cry.

I get up and hug him. I squeeze his shoulders as tightly as I can. He’ll be reporting for duty soon, going off to fight in Lebanon or maybe Gaza or to man a checkpoint in the West Bank.

“Oh, God,” he says again and again and again. I don’t know what he’s crying about. He’s such a decent guy. “I just got the call. My cousin was killed in Lebanon.” I don’t ask him any questions after that; I just hold him as best as I can. Other people waiting outside for their meals look away. A man passes the bar carrying a surfboard. Maimon doesn’t have the details yet, just that it happened more than twenty-four hours ago and they haven’t been able to recover the body yet.

We sit in the restaurant for as long as we can. Maimon will make a joke or try to make light, then he will start crying again. He seems OK for a little while, and then he sees the cover of a book I am reading about Lebanon. “Lebanon,” he says, pursing his lips, shaking his head, trying to keep it inside, tears dripping past his lips.

We drive to the airport. At the terminal, as I am getting ready to leave, Maimon says, “Remember Colorado?”

“Sure.”

“All we did was snowboard all the time.”

“Yeah.”

“Remember when you got fired?” he asks.

“I had stolen a snowboard from Vail Resorts.”

“Yeah.”

We try to laugh, but it’s hard.