Despite once being hailed as a role model, Charlie Chan hasn’t held up well in the nearly one hundred years since his introduction. Many now see the “honorable Chinese detective” for what he is: a caricature plucked from the imagination of a white man. Earl Derr Biggers, to be precise, a Harvard graduate and former newspaperman who happened to stumble upon an interesting item in a Honolulu paper about a real-life Chinese detective named Chang Apana.

The only thing Charlie Chan has in common with the man who inspired him is his ability to reel in the bad guys. Chang Apana was a small, trim man, skilled with a bullwhip like an Asian Indiana Jones, steely-eyed in his pursuit of Honolulu’s criminal element. He was a cowboy, a “paniolo,” in the words of his biographer, Yunte Huang. Not the kind of guy who would be caught eating one too many jelly doughnuts.

Chan, by contrast, is a character only a novelist with a fanciful mind and little actual knowledge of Chinese people could invent. (The same goes for Sax Rohmer’s supervillain, Fu Manchu.) Even among literature’s many beloved detectives, Chan is unique. The affable sleuth first appeared in Biggers’s The House Without a Key, which debuted as a serial novel in the January 24, 1925, issue of The Saturday Evening Post. But it wasn’t until a quarter of the way into the novel that Charlie Chan made his grand entrance:

He was very fat indeed, yet he walked with the light dainty step of a woman. His cheeks were as chubby as a baby’s, his skin ivory tinted, his black hair close-cropped, his amber eyes slanting.

When a woman in desperate need of help learns he’s the best detective in town and is the man assigned to her case, she sputters in protest, “But—he’s Chinese!”

The thing about Charlie Chan is that in the films and television shows memorializing his adventures, he has rarely been Chinese, let alone Asian. “Favorite pastime of man is fooling himself,” as the epigram-spouting Chan might say.

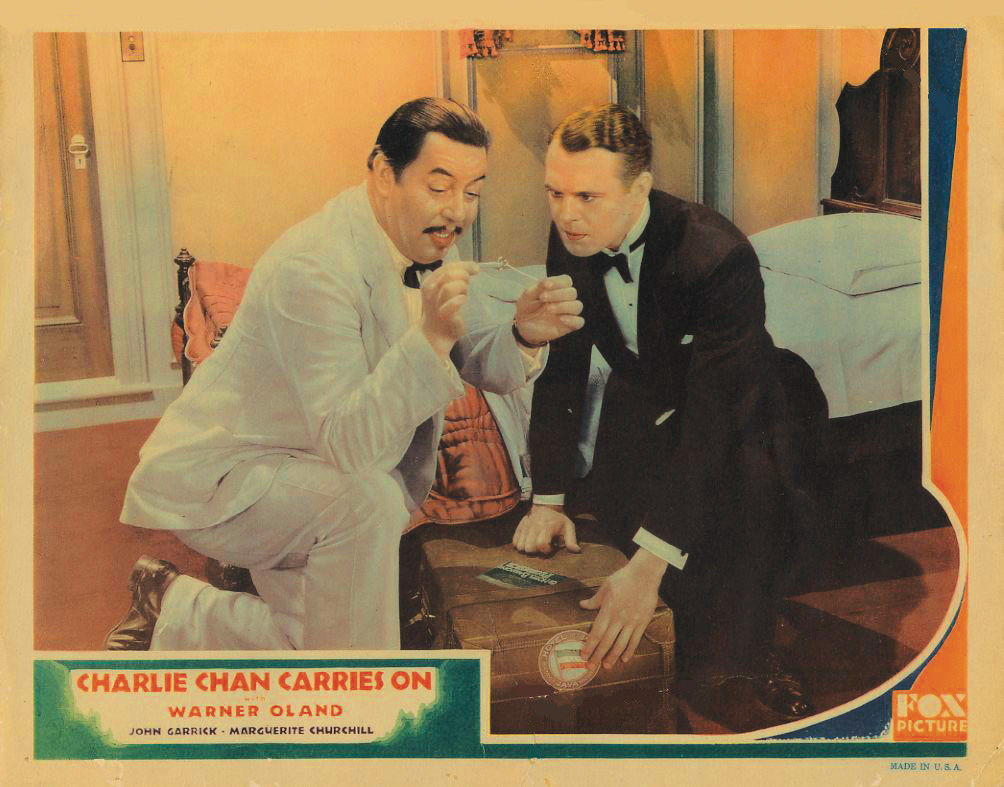

Swedish actor Warner Oland was the first to make Charlie Chan movie-star famous, in 1931’s Charlie Chan Carries On. His yellowface depiction notwithstanding, Oland allegedly used almost no makeup to play the part. He simply combed his eyebrows up, turned the ends of his mustache down, and grew in a black goatee for good measure. Oland played Charlie Chan in sixteen films for Fox Film Corporation (later, 20th Century–Fox) and became synonymous with the detective in the 1930s—fans referred to him more often by Chan’s name than his own. He fell into the habit of speaking in the same proverb-laced pidgin his character was best known for, even in the privacy of his own home. There was no escaping Chan, though that didn’t stop Oland from trying. He nearly drank himself to death, then walked off the set of Charlie Chan at the Ringside one day in 1938 and sailed to his native Sweden, where he caught pneumonia and died.

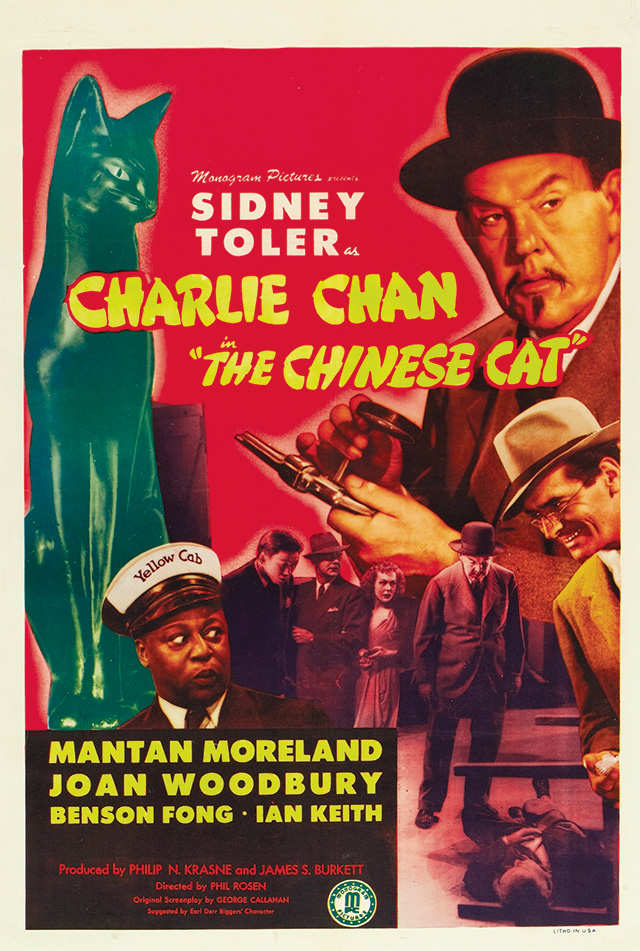

Fox had no intention of letting its best-selling franchise die with Oland, and promptly replaced him with Sidney Toler, who went on to star in twenty-two films, followed by Roland Winters, who starred in six. Later, Charlie Chan was rebooted in a succession of films and television series, impersonated by actors J. Carrol Naish, Peter Ustinov, and Ross Martin. It was a plum job for a character actor of a certain vintage, a role one could age into. All that was required was a fatherly gravitas, some facial hair, and a middle-aged paunch to achieve that pleasantly plump silhouette in a white linen suit. You could be every kind of exotic white man, as the list of actors’ names attests. Just leave it up to the makeup department to tape back your eyes and powder your face a few shades darker.

But what if Hollywood studios had cast an Asian actor in the role of Charlie Chan instead?

In fact, incredibly, they did. And it wasn’t just one Asian actor, but three. Most historians gloss over the unremarkable films they appeared in, which make up the early Charlie Chan canon, because so little is known about them. It’s a bittersweet irony that Charlie Chan has been defined by the white actors who played him in yellowface, yet he debuted in the hands of Asian actors—a detail that is mostly forgotten today. And so, turning this conundrum over in my head, I set out to solve a Charlie Chan mystery of my own.

Not long after The House Without a Key’s success, Pathé picked up the rights to produce it for the silent screen. As the American division of the French studio Pathé Frères, the company was best known for its early silent serials in the 1910s. Such tales perfected the cliffhanger format, like The Perils of Pauline, in which the title character is an independent young woman who insists on pursuing a few adventures before marrying her sweetheart. Unfolding over a dozen or more episodes, serials like this kept audiences guessing, wondering how the plucky heroine would get out of her latest fix.

Although movie serials had lost some of their shine by the mid-1920s, Pathé appears to have allocated plenty of resources to The House Without a Key. The ten-part feature was shot on location in Hawaii, and the studio cast top serial stars Allene Ray and Walter Miller. For the role of the Chinese detective, they brought on Japanese actor George Kuwa.

Born Keiichi Kuwahara to a respected judge in Hiroshima, Kuwa disappointed his father by ditching the family profession and setting his sights on Hollywood. He arrived in Los Angeles in the late 1910s and found work in the flickers playing bit roles in “Oriental” melodramas. He was a working actor, the kind whose parts were sometimes little more than a glorified extra, but he got to act alongside plenty of the silent era’s stars, like Bebe Daniels, Fatty Arbuckle, and Jackie Coogan. Kuwa’s headshot appeared regularly in the Standard Casting Directory and in the classifieds sections of Camera! and Close Up, where he advertised his talent for portraying Japanese and Chinese characters.

It makes sense that Kuwa, and not a white actor made up to look Asian, was the first to play Charlie Chan. Biggers did not originally intend for his Chinese detective to steal the show, and neither did Pathé—it billed Kuwa twelfth in the credits. Chan was a character who served a purpose. He was there to solve the mystery, unveil the villain, and then exit stage left. Director Spencer Gordon Bennet later admitted that The House Without a Key “was no Charlie Chan picture. Chan was just a detective. He wasn’t that involved in the action.”

If the film hadn’t been lost, maybe we could decide for ourselves. Only a lingering still photograph holds a clue as to how Kuwa might have embodied Chan. In it, he wears a dark suit and a straw boater, his neatly cropped hair peeking out from beneath. The defiant killer is at the center of the scene, now in the clutches of his victim’s family members, while Chan is merely a witness standing on the fringes.

The favorable reception of Biggers’s follow-up, The Chinese Parrot, made it clear that the draw was Charlie Chan himself. Universal bought the rights to the novel in 1927 and tapped the newly arrived German import Paul Leni to direct a silent adaptation. Leni was coming off his first Hollywood effort, the widely praised horror mystery The Cat and the Canary, and expectations were already high to see what he could do with a Charlie Chan mystery.

Universal cast well-known regulars to play the leads, including Marian Nixon and Hobart Bosworth. The Chinese American actor Anna May Wong (riding the fame from her role in Douglas Fairbanks’s 1924 blockbuster The Thief of Bagdad) appeared as an exotic dancer who is swiftly murdered for the string of pearls around her ankle—the object at the center of the plot’s many twists and turns. But who was to play Charlie Chan?

Kamiyama Sôjin, a Japanese actor with a storied career, was ultimately selected to try his hand at the role. (George Kuwa apparently wasn’t considered for the role this time around and was instead demoted to background work.) Sôjin, as he was commonly known, had been a leader in Japan’s modern theater movement, producing and acting in productions of Shakespeare, Ibsen, Sudermann, and Shaw. When he and his actress wife, Yamakawa Uraji, arrived in Hollywood on their first trip to America in 1919, they were hailed as “the Sothern and Marlowe of Japan,” a reference to a famous Shakespearean acting duo.

Such lofty comparisons did much to extend Sôjin’s reputation throughout Hollywood. Once he returned in 1923 and was cast in The Thief of Bagdad, his screen presence became self-evident. Critics took notice of his masterful turn as the evil Mongol prince, and he soon gained a reputation for wicked expressions and brooding looks.

According to Sôjin, though, he wasn’t the first in line to play Charlie Chan in The Chinese Parrot. In his memoir, Sugao no Hariuddo (Hollywood without makeup), Sôjin explains that it was actually Conrad Veidt, one of Leni’s longtime collaborators and a fellow German, who was initially cast as Chan. Yet no matter how they did his makeup, Veidt simply didn’t look Chinese.

Sôjin was called in to assist. He was so successful at transforming Veidt’s appearance that Universal wanted to hire him to do Veidt’s makeup for the entirety of the film. Sôjin refused outright. “I told them I was not a makeup man and left,” he recalled. Outplayed, Universal threw up its hands, fired Veidt, and installed Sôjin in his place. Veidt was so shattered, Sôjin later claimed, that he sat in his dressing room and cried. “I felt sorry for Conrad Veidt, so I found a great script called The Man Who Laughs for him,” Sôjin added somewhat sardonically, putting his own spin on the sequence of events. Veidt did later star in The Man Who Laughs, Paul Leni’s next film, but it’s doubtful that Sôjin was the one to suggest the Victor Hugo novel from which the script was adapted.

The Chinese Parrot opened in the fall of 1927 to mixed reviews. Some critics felt the film’s plot was rather thin, leaving little to be surprised about at its resolution. Others, however, were spellbound by the vivid, creepy atmosphere that Leni evoked through his off-kilter set design, wonky angles, and use of camera techniques like double exposure—core features of German expressionism. Above all, Sôjin’s commanding performance, not only as Charlie Chan but also in a series of disguises, seemed to make up for whatever the story lacked.

“The character acting of the Japanese screen player… is perhaps the most interesting of any in the picture,” one reviewer wrote. “True, Sôjin was in his element in such an Oriental role,” another critic observed, “but that doesn’t detract from the remarkable ‘scoop’ he pulled in putting the breathing life into this picture.” A columnist for the British magazine The Sketch remarked, “[Sôjin] juggles his face and body in the most amazing way… His least gesture has intention; his moments of stillness are pregnant with meaning. And, to cap it all, he has a great sense of humour.”

It’s no shock that Sôjin, one of Japan’s preeminent actors, was a marvel as Charlie Chan, bringing his own distinct interpretation to the role. Alas, two months after the film’s premiere, a studio fire destroyed Universal’s print of The Chinese Parrot, most likely the master copy. No other print is known to exist.

A cache of film stills on IMDb offers a small consolation and a chance to search for traces of Sôjin’s performance. In some of the scenes pictured, he’s disguised in “coolie” garb. He stoops over comically, to almost half his height, with an obsequious expression, as he serves various distinguished houseguests from a silver platter. Returned to his upright form as the honorable detective, he has a strikingly different bearing, exuding confidence and cunning. In every frame in which he appears, all eyes are fixed in his direction. “Our gaunt corpse-like Chinese [sic] actor friend So-Jin, with his parchment skin and prawnish movements, retains your almost undivided attention during the time he is seen,” Picturegoer remarked, “and he is seen quite a lot.” I’ll hazard to suggest that Sôjin could have had a notable career ahead of him as Charlie Chan. But that future was not to be.

Earl Derr Biggers was optimistic about cinema’s ability to enshrine his hero in pop culture “as the leading sleuth of his generation.” And though he didn’t have much involvement in the film adaptations of his novels, he did have control over whom he sold the rights to. Biggers admired Sôjin’s prowess as an actor, but, as he wrote in a private letter to his editor, Sôjin gave the appearance of “a long, thin, sinister chink.” He was nothing like the charmingly chubby Charlie Chan that Biggers had dreamed up in his novels. Months later, after being informed by friends and family who had gone to see the finished film and pronounced it “terrible beyond belief,” Biggers lamented, “The general opinion of people out here is that I ought to sue Universal for defamation of character.”

Best-selling author or not, Biggers bought into stereotypes about the Chinese as much as anyone else. In the white racist imagination, a “bad Chinese” was a stealthy schemer who couldn’t be trusted. But not his Chan. By contrast, his creation was a fountain of benign wisdom, there to help the white man in his hour of need. Chan was nonthreatening, childlike in his corpulence. Biggers credited himself with inventing this characterization: “Sinister and wicked Chinese are old stuff, but an amiable Chinese on the side of law and order had never been used.” Some today would call his vision of a “good Chinese” by another name: the model minority.

For the next book in the series, Behind That Curtain, the film rights went to neither Pathé nor Universal, but to Fox Film Corporation. It was also to be the first Charlie Chan flick produced with sound. Thus, even if Fox had thought to cast Sôjin, his halting, accented English made him an unfavorable candidate.

Here’s where the plot thickens. Fox recruited a man named E. L. Park to play Charlie Chan. Though I had long known about Kuwa’s and Sôjin’s stints as the Chinese detective, I hadn’t heard of Park until I received an email from a friend last year, containing a screenshot from an obscure blog with a photo of the actor. Based on his surname, the blogger guessed he must be Korean. More mysterious still, Behind That Curtain was Park’s sole film credit, yet he hardly appeared in it. He was dropped in at the movie’s end, deus ex machina–style, for two minutes of screen time, as the case appears to solve itself. Charlie Chan was but an accessory to one of Scotland Yard’s global crime investigations.

So who exactly was E. L. Park? My search took me to one of the twenty-first century’s most popular sleuthing portals: ancestry.com. (Luckily, this amateur detective already had a subscription.) Soon I was staring at a complete family tree for Edward Leon Park and his relatives. What’s more, Ed Park, as he was more often called, was not the only person in his family to make his way into showbiz. His wife, Florence Park, known by the stage name Oie Chan, and his daughters, Bo-Ling and Bo-Ching, who branded themselves as the “Chinese twins” for their vaudeville routine, were regular bit players in Hollywood.

Several messages and email chains later, I was connected with Bo-Gay Tong Salvador, Ed Park’s granddaughter, who is now in her seventies and working to capture her family’s fascinating history. Bo-Gay greeted me over Zoom from her home in Southern California and told me about her grandfather.

The first mystery she cleared up was that of his ethnicity. Park, she explained, was neither Korean nor white, as some people wrongly assumed when looking at his name on paper. He was a second-generation Chinese American born in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1881, and his Chinese name was Leong Gwai June. At the time, most Americans were unfamiliar with the conventions of Chinese names, which are sequenced with the family name before one’s given name. His older brother’s Chinese name was transliterated into English as Leon Quai Park. Since “Park” was assumed to be his surname, he went by Robert Park. Whether the name was applied to Edward by association or he chose it because he saw the advantages of an Americanized name, Leong Gwai June became known as Edward Leon Park. Leon was a nod to his true family name.

I asked Bo-Gay what led to her grandfather’s foray into Hollywood. Her answer meandered, much like the journey she described. Ed Park was a jack-of-all-trades who did whatever he could to support his family. As a young man, he enlisted in the US Navy, and later served as a cook on the USS Albatross as it charted the waters from San Francisco to Japan on an oceanographic expedition. When he returned to the mainland, he settled down in Berkeley, California, and married Florence Chan, his sister-in-law’s best friend, who had grown up in a Protestant mission home.

In 1910, he was hired as one of the first Chinese interpreters at the newly established Angel Island Immigration Station (the West Coast counterpart to Ellis Island, for processing new arrivals from across the Pacific). Despite his full-time government job, the always-resourceful Park found ways to make a little extra on the side. He ran a produce cart business, bought a farm that raised chickens and pigeons, and helped out at the Chinese World newspaper, where his brother was the managing editor. Park proved his adaptability through his wide-ranging portfolio, and the skills he picked up along the way served him well in his future endeavors. I can imagine a young Charlie Chan soaking up a similar hodgepodge of experiences, background work for his final act as police detective.

By 1927, Park moved with his wife and two daughters, now sixteen and nineteen, to Los Angeles, where he got a job as an interpreter for the city courts and immigration offices. The move was likely influenced by Bo-Ling and Bo-Ching’s desire to break into the movies. The girls were a talented singing and dancing duo and had been performing on the vaudeville circuit since they were preteens. Park also spied a business opportunity. After nearly two decades of experimentation, Hollywood was finally coming into its own.

In addition to his interpreter job, Park opened a Chinese restaurant and the China Costume Company on Alameda Street in downtown Los Angeles. The costume store supplied various studios with authentic-looking garments for their “Oriental” features, which were strangely in demand. One day Irving Cummings, the director of Behind That Curtain, walked into the store and, sizing up Park, decided he’d found his Charlie Chan. Indeed, with his broad oblong face, slightly balding head, and stout figure, Park looked the part. Years later, a newspaper reporter who chanced to meet him recalled being immediately “struck by his uncanny resemblance to Biggers’ fictional Chan.”

Though his cameo in Behind That Curtain amounts to a precious few minutes, Park leaves a memorable impression. He looks dignified sitting at his desk in a three-piece suit and speaks his lines matter-of-factly. While his English lacks polish, it’s infinitely easier to listen to than that of the Scotland Yard inspector, with his drawn-out pronunciation. Park appears most at ease when he gets up mid-conversation to address the racket coming from the building next door. He scolds a young saxophone player in fluent Cantonese, flashes a mischievous smile at the boy’s acquiescence, and then returns to his desk.

Park never acted again, but his one flirtation with Hollywood secured his place in moviemaking history as the first Chinese American to play Charlie Chan. His wife and daughters continued to appear sporadically in films over the years, including in roles as the wife and daughters to—who else?—Charlie Chan. I asked Bo-Gay what she thought of this family legacy (as a three-year-old, she herself appeared in the 1954 film World for Ransom). “While I am proud because they were proud of their accomplishments, I do have mixed feelings,” she said. “I know that many of their roles were relegated to the stereotypes given to Asians.”

Promotional poster for The Chinese Cat (a.k.a. Murder in the Funhouse), a mystery film starring Sidney Toler as Charlie Chan. The film (originally titled Charlie Chan and the Perfect Crime) was the second Charlie Chan movie from Monogram Pictures, and was released in 1944.

Edward Leon Park might not have been an actor or a detective, but in many ways, he’s the Charlie Chan we deserve. Like the fictional Chan, he was a man caught in the crosscurrents of two societies. He was a “culture broker,” as historian Mae Ngai has termed such cultural go-betweens, navigating the worlds of both his community and white American society, always seeking ways to bridge the two. And like Chan, he was a family man who raised his children to join the next generation of Americans building this country. Maybe Ed Park, though overlooked, was Charlie Chan’s truest incarnation.

As Chan himself would say, “Door of opportunity swing both ways.” In this case, the door swung irrevocably shut. Following Park’s appearance, the appetite for casting another Asian actor to play Charlie Chan fizzled out. Biggers, in fact, was ready to give up completely: “The news is all about over there that Charlie cannot be cast—Fox tried every Chinese laundryman on the Coast, but never thought of trying an actor—and the issue looks like a dead one.”

Then Warner Oland came along. He put on the white linen suit, something Chang Apana never wore, and it fit. Just as Biggers had rewritten Chang to match his conception of a Honolulu police detective, Oland recast Charlie Chan in his own image. Chan, at heart, was merely a white man posing in a Chinese detective’s clothing.