Our Eden is before us, not behind us.

—Horace Greeley

Your average letterpress-printing enthusiast1 probably shares this earth with more than sixty thousand like-minded souls. For instance, Briar Press, a popular letterpress community on the web, has nearly sixty thousand registered users. In other words, you could populate a reasonably sized small city with letterpress enthusiasts.

However, of this reasonable number of people using letterpress printing equipment, only a fraction actually use the equipment in its age-old way. Today’s letterpress printer most commonly prints with an image made from polymer and produced using a computer. These “photopolymer” plates are the correct size (.918 inches high, also called “type high”) to fit into an antique press, but they are divorced from the old process in an essential way. Letterpress printing, as the name implies, originally used individual letters (collectively called “type”). Typically, a piece of Anglo/American lead type is a short (.918-inch), thin piece of metal (an alloy of lead,2 antimony, and tin) with the face of a single letter at one end. The typeface is the unique relief design of the letter, cast in reverse.

As you can imagine, if all of the letterpress enthusiasts would fit into a small city, and all of the people who print using old lead type might fit into a small town, then the people who still make that type are exceedingly rare.

If you were to gather up all of the typecastors3 in the world, you would be hard-pressed to fill a lecture hall with them. Some estimates put the number of typecastors at between fifty and one hundred worldwide, maybe a little more. But here we are talking only about people who can cast metal type using existing machines (“typecasters”) that are fitted with the existing dies to make different letters. These typecastors generally do the work as a hobby, and use machines salvaged from local printing offices that have gone out of business. An even smaller number of those own and operate industrial typecasters, machines that, unlike those once used by local printers, can produce large quantities of high-quality “foundry” type.

Of that small number of castors, if you were going to gather the people skilled enough to make the brass die used for casting type (called a “matrix”) for a totally new typeface, you would probably be able to fill one (maybe two) 1993 Subaru wagons.

Theo Rehak is one of these people.

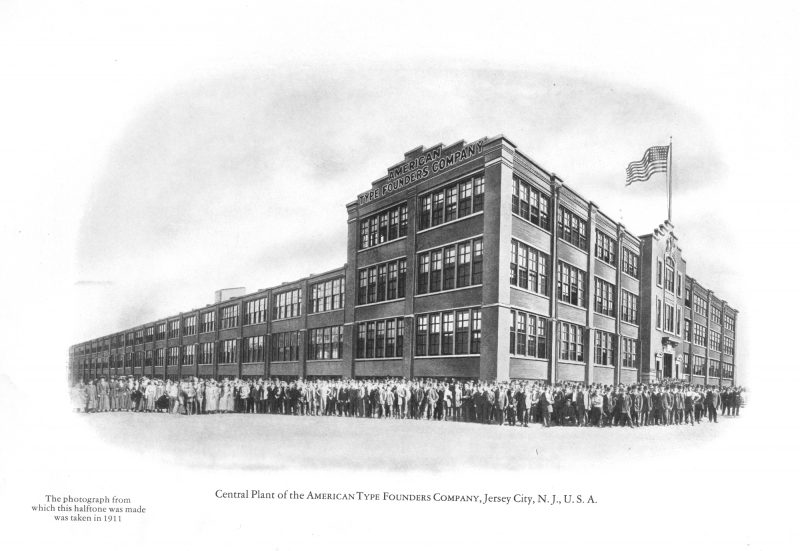

I visited Theo at his type foundry in central New Jersey. The foundry is located in a medium-size purpose-built brown building...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in