One of the most virulent opinions about movies I’ve encountered as a critic—particularly online, where everyone’s a critic—is that popularity is somehow indicative of quality. Consider it the last refuge of the inarticulate: I like what everyone else likes no matter what snobs such as you like. Or more basically: 50 million Spider-Man 3 fans can’t be wrong.

My gut response, sadly, is often the second-to-last refuge of the inarticulate: Yeah, let’s see how long that lasts. Both of us, in other words, are gauging quality through quantity; they’re counting ticket sales, I’m counting years. I assume that Spider-Man 3, silly and effects-laden, is a diversion for our time and no other, and in fifty years, if we’re still watching movies, the only reason anyone’s going to be watching this thing is for nostalgic purposes. I also assume it’s always been thus. If I were to examine the weekend box-office profits—that weekly measure of a movie’s mettle—from fifty years ago, that list would be filled with the relics of a bygone era: once-popular diversions that have long since sunk from view.

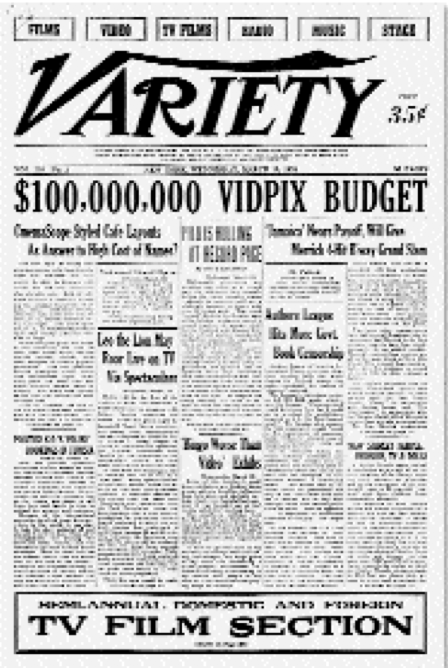

So I went looking. Here, according to the March 19, 1958, Variety, are the movies Americans went to see fifty years ago this week:

- The Bridge on the River Kwai

- The Brothers Karamazov

- Witness for the Prosecution

- Around the World in 80 Days

- Search for Paradise

- Raintree County

- A Farewell to Arms

- Paths of Glory

- Cowboy

- …And God Created Woman

Whoops. Of the ten films, I knew eight, I’d seen four, and I loved two. These were films admired in their day (twenty-nine Academy Award nominations, twelve wins, including two for Best Picture) and admired in ours (three rank on IMDb.com’s top-250 list, including Paths of Glory at number 43).

Some of our familiarity with the titles on the list is misleading. We recognize A Farewell to Arms and The Brothers Karamazov because of Hemingway and Dostoyevsky, not Hollywood. I couldn’t have told you who starred in the former (Rock Hudson and Jennifer Jones, it turns out), and I only knew the latter because I was once a Trekkie and the film includes the screen debut of William Shatner.

Eight of the ten, in fact, are based on novels and plays. So the most popular storytelling medium of its time (movies) was fending off attacks from its eventual usurper (TV) by relying on the very forms it usurped (novels and plays). Nice.

That fight against TV—throughout the 1950s, TV-set sales...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in