Writers’ house museums are melancholy places, scattered across the literary map of the U.S.A. I’ve been to a dozen: Mark Twain’s house in Hartford, Connecticut; Harriet Beecher Stowe’s house in Hartford, Connecticut; Walt Whitman’s house in Camden, New Jersey; Emily Dickinson’s house in Amherst, Massachusetts; Herman Melville’s house in Pittsfield, Massachusetts; Edith Wharton’s house in Lenox, Massachusetts; Jack London’s house in Glen Ellen, California; Ernest Hemingway’s house in Key West, Florida; Paul Laurence Dunbar’s house in Dayton, Ohio; William Faulkner’s house in Oxford, Mississippi; Thomas Wolfe’s house in Asheville, North Carolina; Nathaniel Hawthorne’s house in Concord, Massachusetts.

I have thirty-eight more to go.

Writers’ houses are by definition glum. They are often obscure, undervisited, quiet, and dark. They remind us of death. And they aim to do the impossible: to make physical—to make real—acts of literary imagination.

Going to a writer’s house is a fool’s errand. We will never find our favorite characters or admired techniques within these houses; we can’t join Huck on the raft or experience Faulkner’s stream of consciousness. We can only walk through empty rooms full of pitchers and paintings and stoves.

These sleepy museums tucked into residential streets expose the heartbreaking gap between writers and readers. Part of the pull of a writer’s house is the desire to get as close as possible to the moment of creation, to the precise, generative, original “Aha!” But we can never get there. The houses become theaters of Zeno’s Paradoxes: writers and readers are always separated, and the act of reading is always severed from the act of writing. That is why Socrates feared its invention. Unlike speech, writing is inanimate, divorced from the living intelligence that produced it. It is silent in the face of questioning, has no one to protect it, and, if you ask it a question, it “preserves a solemn silence.”

Writers’ houses are like writing: at once themselves (marks on paper; a desk) and something else (emotions; a site of literary creativity). They are teases: they ignite and continually frustrate our desire to fuse the material with the immaterial, the writer with the reader.

So why do I go? Because, writer and reader both, I want to close those gaps. I want to perform the ritual of taking smaller and smaller steps, knowing I will never reach the line. Like any other frustrated desire, getting closer creates greater longing. Melancholy is the price of admission.

*

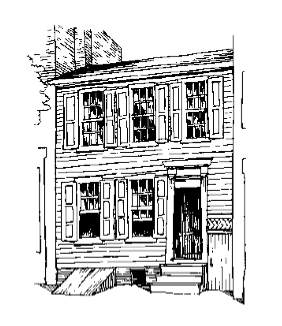

Walt Whitman knew this desire and its impossibility well. His poetry revolves around the search for a connection between things and spirit, readers and writers. In his autobiography, Specimen Days & Collect, written in his modest row house in Camden, New Jersey, Whitman claimed that...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in