I.

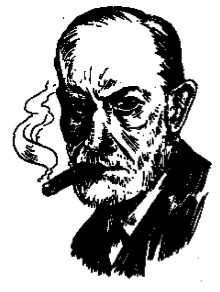

A friend of mine, born, like me, in the Me Decade, once said, “I was raised a Freudian from birth.” Never mind the suburban gothic features of his particular case, or what exactly my friend meant by this exaggeration. (The Frankfurt School famously claimed that in psychoanalysis only the exaggerations were true.) In a sense what he said goes for all of us. As Auden wrote in 1939, in his elegy for Sigmund Freud:

If often he was wrong and at times absurd

To us he is no more a person

Now but a whole climate of opinion

But in Auden’s day that was still a microclimate, confined to the avant-garde and the school-wise elite at a time when to most people the shock therapy of modernism still seemed more of a shock than a therapy, and when only a tiny portion of the public had had its adolescence extended in the form of a college education. It happened, in the postwar years, and especially in America, that the mass ascendancy of Freud and his followers coincided with the first era of mass higher education. At the same time the modernist culture being enshrined in universities throughout the fifties and sixties tended to promote unsystematic psychological research on oneself, such as Woolf and Proust and Yeats had carried out. And of course it didn’t hurt that the undoing of hang-ups, otherwise known as inhibitions, had gained a new plausibility with the advent of the Pill. Make love not war was a cruder choice than Freud would have proposed, but it was also a popularization, whether people knew it or not, of his late metapsychology, which pits a love instinct—Eros—against Thanatos, the death-and-destruction drive, in a permanent contest for our energies. Love or war: The idea, above all in Herbert Marcuse’s Marxist update of Freud, was that you had no choice but to make one or the other, and that a society like the United States, with energy to spare, was bound to produce an awful lot of surplus pain or pleasure.

If you’re pushing thirty or not too far past, your parents were likely coming of age during this heyday of pop and academic Freudianism, and they didn’t need to be lefties or swingers to inhale the climate. Sure, the counterculture was therapeutically-minded, with its ideological sponsorship by Freudians like Marcuse and Erich Fromm and Norman O. Brown, its paperback copies of sex-prophets Henry Miller and D. H. Lawrence, its slogans—in Paris, in 1968—like It is forbidden to forbid, and its use of the free-associative drugs par excellence, weed and acid, the latter having enjoyed a long romance among accredited psychiatrists. But the...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in