Hollywood is burning. Crimson flames consume the great Skull Island gateway from King Kong and the giant wall of Jerusalem from Cecil B. DeMille’s The King of Kings. The incongruous artificial city has been disguised as Atlanta for the filming of Gone with the Wind (1939). The man responsible for capturing the destruction on film is William Cameron Menzies.

Menzies was an art director, production designer (a title he invented himself), producer, and director, the man who created the look of Gone with the Wind, unifying the work of a posse of directors. His career rocketed from big-budget epics to low-rent trash, but there’s a stark visual consistency to it: massive, overwrought close-ups, compositions in sweeping arcs, clinical symmetry or radical displacement upward or downward, leaving blind walls of empty space staring at the viewer while the subject of the shot nestles at screen’s edge, hemmed in by nothingness.

The films he directed rove across genres and the political spectrum. Address Unknown (1944) is an excellent anti-Nazi propaganda piece, but when the cold war got frosty, The Whip Hand (1951) was swiftly rewritten so that the villains were commies instead of fugitive Nazis. Invaders from Mars (1953) could have pursued a Red Scare subtext but preferred to chase the visual possibilities of dime-store sci-fi, the child’s-eye view, and the dream sequence. And The Maze (1953) is a movie about a giant frog.

Menzies’s binding vision was not thematic or political, but a philosophy of the image itself: a vision of cinema as a dream, hatched in the mind of a single artist, unleashed via a flat screen. The cinema’s power was visual, made up of composition and movement, and the man best suited to control the image was not the director, producer, or even the cinematographer, but the designer.

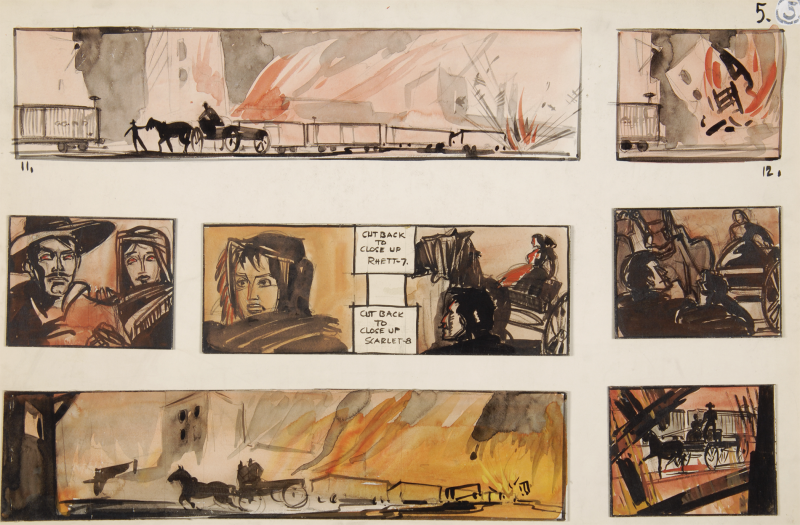

Whatever his listed role (and credits are especially deceptive with this unclassifiable multitalent), the importance of Menzies to a given production can be assessed by the evidence on-screen. He took the stance that each shot of a film should express forcefully a single, striking visual idea. By sketching not only the layout of the set but the camera position, the movements of the actors, and the lighting design, the designer could map the entire surface of the film.1

This emphasis on storyboard preparation points up a couple of weaknesses in the movies Menzies directed: they don’t always move with the fluidity of less predetermined films, and the performances, though often very fine, tend to be subjugated to the needs of pictorial composition.

A former children’s book illustrator, Menzies had been working as an art director in film since 1918, when he got his big break designing the Douglas Fairbanks spectacular The Thief of Bagdad (1924) in collaboration with Anton Grot. Grot was perhaps the top man in the field, and would go on to help create the Warner Bros. look, with expressionistic zigzags of light and shade in crime pics like Little Caesar (1931), and implausibly glossy Elizabethan palaces for The Sea Hawk (1940). The two men’s styles clicked, both favoring the idea of set designs that dictated the camera’s position: the designer composed the film. For the Arabian Nights epic The Thief of Bagdad, Menzies and Grot blended mock–Middle Eastern fairy tale with art deco and art nouveau, constructing a mammoth walled city dominated by a soaring white palace.

It’s a gigantic yet strangely claustrophobic film: the city is so vertiginous, all narrow alleys hemmed in by towering minarets; the exteriors feel like interiors. Outside the city, the walls dominate the frame, blotting out the sky, cramping the Sahara. When Fairbanks travels, we see stretches of desert that shade imperceptibly into starry skies, and canyon passes that fill the screen with massive stone escarpments. Journeys under the sea, and to the moon, are equally confined, despite the grand scale, and Fairbanks’s boat is tossed, Fellini-style, upon a sea made from plastic sheeting.

The huge scale and success of the Fairbanks swashbuckler established Menzies at the peak of his profession, and he went on to design numerous historical epics. The John Barrymore vehicle The Beloved Rogue (1927) conjures fifteenth-century Paris with a cartoony expressionism of warped angles and sloping, curving walls. Stonework becomes organic, towers lean and bulge, and rooftops form erratic alpine slopes. It’s hard to imagine Dr. Seuss arriving at the loopy architecture of his books without Menzies’s example to follow. The film’s casting adds to the grotesque carnival feel, with Barrymore accompanied by bulbous, emaciated, and stunted sidekicks to emphasize his own athletic perfection: the action passes like a storybook brought to life.

The coming of sound alarmed Menzies because it threatened to subjugate everything to the placement of hidden microphones instead of compositional principles. Early talkies were often stilted and static, like stage plays filmed from the stalls. But the chaos wrought by the new medium also allowed Menzies to pitch for a greater role in the process. And for Bulldog Drummond (1929), he wrangled his way into the position of cowriting the screenplay, with an eye to visual possibilities.

The result is still somewhat rigid and stagy, but it comes alive in key scenes in which Menzies got his way. An opening sets up the boredom of a London gentlemen’s club: We drift at floor level past somnolent old buffers merging into their armchairs in a fug of cigar smoke. The slinking camera and low angle make the figures seem immobile as a mountain range. Dastardly doings later in the film take place in a mad scientist’s lair (a favorite Menzies haunt) abubble with mysterious chemicals in looming close-up. Menzies racks the beakers flat across the screen, as if they’d been glued to it: we see the actors through glassware darkly.

Alibi (1929) is another of those very early talkies where the dialogue scenes sometimes feel as if the camera had been left running by mistake, but Menzies’s touch shows in interstitial moments of visual panache. The establishing shots, normally mere backdrops and signposts, form thrusting perspectives, the camera sucked toward their art-deco vanishing points, dragging the viewer by the eyeballs.

Menzies’s screenplay for Alice in Wonderland (1933), though co-written with the eloquent Joseph Mankiewicz, is a grab bag of favorite moments from both Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Scenes are chosen for visual possibilities rather than any kind of logic, even the logic of the absurd. (Casting opportunities may also have driven the plotting: W. C. Fields as Humpty Dumpty is inspired/inescapable.) To watch it is to realize how rationally organized Lewis Carroll’s nonsense really is. Menzies has Alice go down a rabbit hole and through a mirror, just because he can’t resist those images. Though the rationale behind Carroll’s absurdity escapes Menzies, he certainly revels in the distortions of scale, bizarre conjunctions of scenery and character, and disintegrating reality: the film’s best sequence is the nightmarish climax in which the fabric of Alice’s dream falls apart in a dizzying succession of sight gags and jarring, grotesque images. Menzies was good at dreams, Hollywood-style, and even better at the disorientation that comes when a dream stops flowing smoothly and waking life batters through.

The directors Menzies designed for fall into roughly three classes. There are those without visual style, who would be subsumed by their designer’s plan, except when they resisted it and fell flat on their faces. Then there are those who had such strong visual personalities that they could reduce Menzies to the role of a regular art director without the work suffering. Hitchcock enjoyed the huge and elaborate European cityscapes Menzies built for Foreign Correspondent (1940) without any of the results greatly resembling the Menzies style. (Spellbound, from 1945, is a special case: the Freudian dreamscape, usually credited to Dalí and Hitch, is largely the product of reshoots directed by Menzies.) And then there are a couple of directors whose work blends so well with Menzies’s that it becomes hard to see where one begins and the other ends.

Anthony Mann, a hard-boiled Hollywood pro whose career roved from noirs to westerns to epics, made only one movie with Menzies, Reign of Terror (or The Black Book), a 1949 French Revolution potboiler that reaches the level of high art through its unceasing, sweat-soaked hysteria and aggressive visual brio. Mann and Menzies form two points of a crazy triangle here, the third being the great noir cameraman John Alton. The resulting images are all thrusting gargoyle faces in fish-eye distortion, clutching shadows, and funky, teetering compositions. They combine the most extravagant characteristics of all three eccentrics, along with punchy comic-book dialogue (Robespierre’s “Don’t call me Max!” is a classic of Hollywood history-making) and a zany, convoluted espionage plot.

Sam Wood, wing nut and journeyman director, formed a long-lasting association with Menzies in which he seemed to channel all that stylistic excess while adding a greater interest in performance, allowing more fluidity to the style: Wood is interested in people as more than mere elements in a composition, so the scenes play more smoothly, even with all Menzies’s jarring shock-cuts, leering close-ups, and extreme angles. A movie like Ivy (1947) will still throw in spectacular point-of-view shots. If Joan Fontaine is staring with fascination at that bottle of poison, why is four fifths of the image an empty void beneath the tabletop? To make the image itself as arresting as its meaning.

The Wood-Menzies pairing (with Menzies usually taking producer credit, leaving us to deduce his other roles by the unmistakable evidence on-screen) includes three classics of Americana, The Pride of the Yankees (1942), with Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig, and the weird double bill of small-town expressionism Our Town (1940) and Kings Row (1942). In the first, Thornton Wilder’s empty stage becomes a visible, if sometimes phantasmal, town. During the opening, it dissolves mistily through different historical periods. By the end, it has transformed into an ethereal afterlife where monumental figures appear in impossible deep focus. Kings Row, the movie in which Ronald Reagan says, “Where’s the rest of me?”, is hell to Our Town’s heaven. Based on a censor-baiting best seller, it serves up a little community of staggering corruption and the darkest of secrets, the Twin Peaks of its day. Menzies obliges with phantasmagorical angles and Brobdingnagian foreground props, turning the most innocent kitchen into a fun-house mirror-world.

Mr. Lucky (1943) features a striking scene change that illustrates Menzies’s way with shapes. As a character begins a story, we pull back along an alley made of piled crates until we are viewing it through a narrow vertical slit, which in a quick dissolve becomes the crack in the doorway of a great warehouse, slowly opening to reveal a new scene: a beautiful fake ship at harbor. By reducing a moment to lines and points, Menzies can transport us through space and time, traveling by geometry.

Imported to Britain in 1936, Menzies oversaw Things to Come, personally scripted by H. G. Wells. The goal may have been a rebuttal to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), but with its characters reduced to political positions, its emphasis on scale and sweep over human drama, and its absolute avoidance of humor, Things to Come exaggerates precisely those qualities of Lang’s film generally cited as flaws. “I’ll never see another movie you recommend,” pouted Stanley Kubrick, after Arthur C. Clarke arranged a screening during prep for 2001: A Space Odyssey.

If the film is dramatically wooden, the design is Plexiglas and neon, Lucite and white plaster. Working with the great designer Vincent Korda, Menzies rightly treats the clumsy script as an opportunity for dizzying perspectives, outsize sets, gleaming surfaces. Actors can contribute to this vision mainly by wearing gigantic hats, or by allowing themselves to be positioned just so amid the sweeping ellipses and towering shafts.

But Menzies’s masterpiece in the sci-fi realm may be Invaders from Mars, a cheapjack flick-book of bubblegum trading cards that opens a cardboard door into the unconscious. A final reveal exposes the whole sham as a child’s nightmare, but the movie itself operates in three somewhat distinct ways. The first third is eerily oneiric, with Menzies’s sets playing sinister tricks on our eyeballs: a wooden fence fails to shrink as it recedes into the distance, because Menzies built it to get bigger as it got farther away (making sets that could be shot from only one angle was an old German expressionist ploy). As the paranoia peaks, we switch to a lurid comic-strip fantasy. Shots even seem to have space built in for speech bubbles, great empty walls oppressing our boy wonder. The final section, which by rights should be a snappy all-a-dream resolution, devolves into sheer avant-garde abstraction, with the whole movie looping and double-exposing on top of itself as the young protagonist struggles toward consciousness through a mire of free-floating ghost images. Hollywood never got crazier than this.

The plot of The Maze, though, seems like an attempt to push things even further. The very peculiar tale of a man who’s never physically developed past the amphibian phase of evolution in his Scottish castle, it’s Menzies’s final feature as director, and his only one in 3-D. But really, the extreme visuals of his previous work don’t require such a gimmick. For years, rumors persisted that Invaders from Mars was shot in three dimensions, whereas it only looks as if it was. And Address Unknown, arguably his best straight-up drama, has moments that produce real flinches, as Menzies propels a gaggle of bulbous-headed Aryan children at us, or shows Nazi storm troopers bayoneting their way through a safety curtain, effectively ripping through the cinema screen to come and get us.

While Menzies was a Hollywood animal to his core, his success subverts many of the accepted wisdoms of filmmaking. He often managed to be the true creative begetter of his films, but without being the director or producer. In fact, in the strictly regulated hierarchy of the film crew, Menzies seems to defy the imposition of definitive roles. He was an artist, and his medium was the moving image, and he seized control over it whatever job title he received—or made up for himself.

1. Similarly, Arnold Schoenberg, invited to compose music for The Good Earth, offered to do so only if he could take command of every element of the sound track, including the dialogue. MGM said no. Menzies somehow got away with an equally bold approach.

Thanks to David Bordwell and Glenn Erickson for their previous scholarship and insights on the subject of Menzies and his films.